Geotimes - April 2001: News Notes

aprilheader.html

Geotimes - April 2001: News Notes

aprilheader.html

News

Notes

Field

Notes

Adios,

La Niña

Satellite

images of water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean indicate that this fall

might mark the end of the three-year reign of La Niña climate conditions.

Over the next several months, scientists will continue to use satellite

data and computer climate models to monitor the Pacific decadal oscillation

that determines La Niña and El Niño conditions.

Satellite

images of water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean indicate that this fall

might mark the end of the three-year reign of La Niña climate conditions.

Over the next several months, scientists will continue to use satellite

data and computer climate models to monitor the Pacific decadal oscillation

that determines La Niña and El Niño conditions.

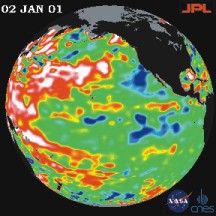

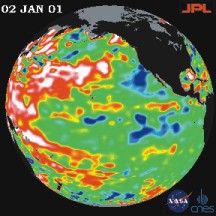

[At right: This image of

North America and the Pacific Ocean was taken by the NASA-French TOPEX/Poseidon

spacecraft on Jan. 2. The red regions indicate warmer sea temperatures

and blue indicates cooler temperatures. The pattern seen here is characteristic

of a weak La Niña.]

Changes in the Pacific Ocean are most unpredictable between March and

May, making those ideal months for using satellite monitoring techniques

to gather as much information as possible. One of the satellites that climate

modelers use is the NASA-French TOPEX/Poseidon spacecraft.

If this fall does usher in El Niño, NOAA scientist Vernon Kousky

doesn’t expect that it will be as strong as the conditions in 1997 and

1998 because strong El Niños typically alternate with weak ones.

But it will bring rain to California and the southeastern United States,

as well as cooler temperatures in the southwestern states and warmer temperatures

on the west coast of Canada and Alaska, according to NASA.

LW

|

This partially blurred image

of Eros was the last taken by NEAR Shoemaker. As NASA engineers directed

the spacecraft toward the asteroid on Feb. 12, NEAR captured this image

just before it crash-landed. It was taken from a range of 420 feet (130

meters) and shows an area 20 feet (6 meters) across. When NEAR landed on

Eros, image-data transmission stopped, as shown by the blurred vertical

lines at the bottom of the image. See also News Notes, End

of NEAR.

|

Vent

relationships

In a slow game of connect the dots, biological oceanographer Cindy Lee

Van Dover of the College of William and Mary in Virginia is threading together

a hypothesis that biodiversity differs among hydrothermal vents around

the world because of geology. At the annual meeting of the American Association

for the Advancement of Science on Feb. 16, Van Dover reported finding new

data points that indicate a possible link between the rate of sea-floor

spreading and the number of different animal species found around a vent

field.

Van Dover and her students collected and counted species larger than

270 micrometers in size from mussel beds at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the

Northern East Pacific Rise and the Southern East Pacific Rise. The number

of species increased at sites with faster spreading rates. The site on

the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the spreading rate is about 20 millimeters

a year, had less than 25 different species of animals, including juveniles.

At the other end of the spectrum on the Southern East Pacific Rise, where

the tectonic plates are diverging at a rate of almost 160 millimeters a

year, Van Dover found about 50 different species.

Her study area on the Mid-Atlantic ridge had vents that were more stable

but farther apart than vents on the East Pacific Rise, where vents are

close together and short-lived, Van Dover says. These spatial variations

could affect biodervsity, she adds. Although her working hypothesis will

need a more comprehensive data set to link species richness with tectonics

and geography, Van Dover is encouraged with her primary results, she says.

CR

Satellite

images of water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean indicate that this fall

might mark the end of the three-year reign of La Niña climate conditions.

Over the next several months, scientists will continue to use satellite

data and computer climate models to monitor the Pacific decadal oscillation

that determines La Niña and El Niño conditions.

Satellite

images of water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean indicate that this fall

might mark the end of the three-year reign of La Niña climate conditions.

Over the next several months, scientists will continue to use satellite

data and computer climate models to monitor the Pacific decadal oscillation

that determines La Niña and El Niño conditions.