Black

Tide

Christina Reed

When the oil from the tanker Prestige began washing

up along Spain’s northwestern coast last November, it wasn’t the

kind that leaves a slippery, thin sheen on everything it touches. This was

heavy, refined oil. “You could pick it up with a pitch fork,” says

oceanographer Ed Levine of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA). And unlike other spills, such as the Exxon Valdez for example, the

Prestige spill didn’t happen in just one day. “It’s still leaking,

and has been leaking for months,” Levine says.

With

regional elections coming up in May, the continuing disaster of the Prestige

has the Spanish government on the defensive. In response to this spill, both

the Spanish and French governments have declared a unilateral ban on single-hulled

tankers in their waters. But the Spanish government’s decision to move

the Bahamas-registered, Liberian-owned and Russian-chartered Prestige away

from shore has resulted in outrage from the Spanish community.

With

regional elections coming up in May, the continuing disaster of the Prestige

has the Spanish government on the defensive. In response to this spill, both

the Spanish and French governments have declared a unilateral ban on single-hulled

tankers in their waters. But the Spanish government’s decision to move

the Bahamas-registered, Liberian-owned and Russian-chartered Prestige away

from shore has resulted in outrage from the Spanish community.

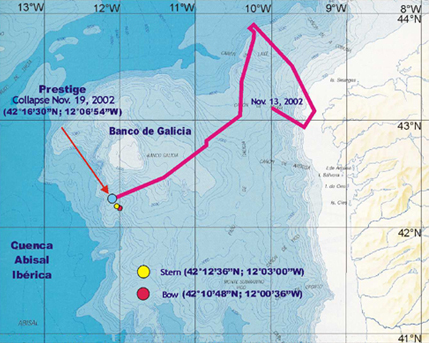

Map modified from

WWF-Spain.

In a letter to the editor of the journal Science published Jan. 24,

422 marine and atmospheric scientists from Spain protested against what they

considered a scientifically unfounded decision by the government to move the

Prestige. “Unfortunately, government officials still sustain that the

decision taken was the best possible one,” says Pablo Serret of the University

of Vigo and lead author of the letter. “This should imply that the management

of a new, similar accident would be the same, which is especially worrying

because of the high traffic of tankers in this region.”

The scientists represented 32 universities and six research institutions.

In their letter, they accused the Spanish government of failing to obtain

scientific input before moving the Prestige out to sea. The dominant winter

winds in the region are west-southwesterly and the ocean currents run south

to north up the coastal slope, they wrote. The decision to move the vessel

offshore, from about 43 degrees North latitude and 9.5 degrees West longitude,

to the southwest was “a consequence of poor communication between government

officials dealing with the spill and the scientific and technical communities,

rather than a deficit of knowledge,” they wrote. Instead of confining

the oil spill close to the coast of Galicia, by moving the vessel further

out to sea the government enabled the oil spill to spread from Portugal to

France, the scientists contend. Indeed, the oil has spread over more than

900 kilometers of the European shoreline, causing an estimated $1 billion

in cleanup costs.

The government also now faces lawsuits from ecologists and activists in the

lobbying group Nunca Mais, formed after the Prestige oil spill to “Never

Again” experience a similar disaster. On Feb. 23, hundreds of thousands

of protesters marched through the streets of Madrid to demonstrate against

the government’s handling of the situation.

Beginning in December, three teams of scientists from NOAA traveled to Spain

for two weeks each to help with the immediate cleanup efforts and provide

advice for managing the years of cleanup to come. In turn, the American scientists

gained insight in dealing with a very different type of oil spill than what

they have seen in the past. “There was so much and it kept coming in

waves. In terms of planning, it wasn’t let’s clean this beach tomorrow

and go someplace else after that,” Levine says. Because new oil would

arrive, “we were cleaning one beach for days and weeks.” NOAA has

been following the long term impact of the Exxon Valdez spill for 14 years,

and found that although the Prestige went down with almost twice the amount

of oil spilled by the Valdez, in Spain the cleanup will be able to proceed

year-round verses the spring and summer window of opportunity for cleanup

in Alaska. This time advantage will be important in pursuing cleanup plans

as the oil the Prestige spilled is much heavier and more persistent than the

crude oil that the Valdez spilled.

The disaster began when the Prestige sent a mayday call to the Spanish coastguard

on Nov. 13. High seas and heavy winds left the 26-year-old ship with a 9-

to 15-meter crack in the middle of its single hull and listing at a 45-degree

angle. By the end of the day, the crack had leaked a pool of oil around the

ship a mile wide. Its engines off, the Prestige drifted east within 5 kilometers

of the coastline, according to reports. The next morning residents of Muxia

awoke to the sight of the listing tanker offshore. “It was a horrifying

scene. We went to bed thinking the boat was 22 miles [37 kilometers] offshore

and there it was right off our beach. Everybody was terrified,” Ramón

Perez Barrientos, head of civil defense in the fishing village, told The

Wall Street Journal.

After an all-night struggle, tugboats secured the tanker on Nov. 14 and a

helicopter check of the vessel indicated its precarious physical condition.

Jose Luis Lobez Sors, director general of Spain’s merchant marine service,

gave the first order to tow the vessel out to sea. By the time the Dutch salvage

company SMIT, which received the contract to rescue the vessel and its cargo,

had a chance to board and investigate the Prestige, it was 2 a.m. on the morning

of Nov. 15. The tugboats had towed the leaky Prestige back out to sea about

40 kilometers.

SMIT deputy chief executive, Geert Koffeman, met with Spanish government officials

to discuss changing the direction of the vessel and bringing it into La Coruña

Bay to attempt salvaging the oil. He failed, however, to convince the government

leaders to change their plans.

The Prestige broke in half and sank on Nov. 19. About 4,000 metric tons of

oil escaped before the ship went down about 200 kilometers west of Spain.

The two sections came to rest some 3,500 meters apart with about 73,000 tons

of oil still leaking at a rate of 125 tons a day. As of March 13, “Half

of the oil is still there, at 3,200 meters depth. Just a time bomb,”

says Enrique Alvarez Fanjul, marine environment department head for the Ports

of the State in the Ministry of Public Works and the Economy.

Madrid has steadfastly supported its decision to move the Prestige out to

deeper water. On Dec. 16, Spanish Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar told the

Spanish parliament, “I am convinced that the decision that was taken

is the correct one and that to distance the ship [from the coast] was the

least bad of all possible decisions. And I take responsibility for that decision

with all its consequences.”

This is not the first time authorities in the region have seen an oil spill

on their beaches. In December 1992, the Aegean Sea tanker crashed on the rocks

beneath the Torre de Hercules lighthouse, contaminating La Coruña beaches

with almost 80,000 tons of crude oil. In the state of Galacia, the fishing

industry struggled for years to recover. Spain’s Minister for Internal

Development Francisco Alvarez Cascos is reported to have authorized the decision

to keep the Prestige away from the coast after consulting with civil servants

from La Coruña and Galicia.

After the ship broke and as it began sinking, the Spanish authorities contacted

the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) at Stennis Space Center in Mississippi

to help them with monitoring the ocean currents and determining what direction

the oil would travel. “We had models up and running within four hours

of agreeing to provide help to the Spanish government,” says Capt. Robert

Garrett, military deputy of NRL. Looking at the situation in retrospect, Garrett

is sympathetic to the Spanish government’s decision to try and keep the

tanker as far from the coast as possible. “Somebody would question their

sanity no matter what they did,” he says.

On Dec. 9, Spain’s equivalent of the National Academy of Sciences formed

a scientific committee to decide about the fate of the remaining oil in the

wreck while France began patching leaks in the tanker using its mini-submersible

Nautile. A second committee would address the cleanup, restoration and additional

matters regarding the spill. In January, the Nautile succeeded in slowing

the leakage rate from 125 tons a day to about 80 tons a day. And as of mid-March,

all of the remaining holes had patches although only half of the original

77,000 tons of oil remained in the vessel. The patches are expected to hold

for a year, giving Spain a rough deadline for either removing or encasing

Prestige’s remaining cargo.

After four months of laboriously scooping oil, the thousands of volunteers

working with the Spanish Army have a clean slate of sandy beaches, but are

still struggling to clean the hard-to-reach rocky shores and reefs. And “from

time to time there is a new wave coming ashore, especially in the north coast

of Spain,” Fanjul says. “A huge amount of fuel was injected into

the Bay of Biscay circulation and from time to time it appears somewhere in

the North. If it is located on time it is followed and forecasted, thanks

to NRL data and other inputs.” During the International Oil Spill Conference

in Vancouver, B.C., from April 6 to 10, scientists and government officials

are expected to discuss the next phase in the cleanup of Spain’s black

tide.