For centuries,

people living in southeast and central Asia have scoured stream and river floors

for the world’s most prized gem rubies. The rubies arrived there in marble

deposits, flushed out of mountains by millions of years of weathering. However,

scientists have not understood why these sparkling red gems — aluminum

oxides with chromium or vanadium — lie in the metamorphic limestone, a

rock that traditionally holds little, if any, of those elements.

For centuries,

people living in southeast and central Asia have scoured stream and river floors

for the world’s most prized gem rubies. The rubies arrived there in marble

deposits, flushed out of mountains by millions of years of weathering. However,

scientists have not understood why these sparkling red gems — aluminum

oxides with chromium or vanadium — lie in the metamorphic limestone, a

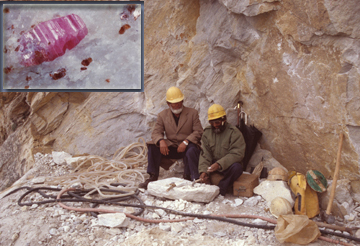

rock that traditionally holds little, if any, of those elements. Two men hammer rubies out of marble in a mine in Kashmir. A new model shows how, why and when gem rubies from southeast and central Asia were encased in marble matrices (upper left). Photos courtesy of the Institute of Research for Development.

A French team of researchers, however, says it has figured out how and why the rubies got there, and has produced a model to help these southeast and central Asian countries locate and exploit the precious resource.

“To my knowledge, this model is the first comprehensive one of ruby deposits,” says Anthony Fallick, director of the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre in Glasgow. The practical worth of such a model in economic geology is enormous, he says, “and there is every reason to hope that the new ideas should assist development of the natural resources.”

Virginie Garnier, Gaston Giuliani and Daniel Ohnenstetter developed the model to do just that. They work for the French Institute of Research for Development (IRD) and the National Scientific Center of Research, two government-sponsored science and technology research institutes that aim to aid in the sustainable development of developing countries. “With this mission in mind, we went into the field in Vietnam with scientists from universities, international corporations, governments and mining companies,” Giuliani says, to look at the country’s mineral resources.

While studying the bedrock in Vietnam in 1998, the French team found rubies, which were always in marble deposits, Giuliani says; however, the marble deposits did not always hold rubies. Over the next few years, the researchers went to Pakistan, Kashmir and Nepal, and studied samples from Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Myanmar (formerly Burma), to understand the connection between rubies and marble.

All across the region, the researchers saw a surprising pattern emerging — rubies only occurred in the marble where evaporites were present. “Where we found salts and marble, we found rubies,” Giuliani says.

Ordinarily, the high temperatures and pressures associated with metamorphism would “destroy the evidence” of evaporites, Fallick says. However, a rare moment in geologic time preserved these evaporites, Garnier says, when the Eurasian and Indian plates collided, raising the Himalaya Mountains.

The ensuing metamorphism melted the salts, which held traces of aluminum, chromium and vanadium from clay minerals, and set the fluid salts in motion. The fluids’ interaction with the marble caused chemical reactions that freed the trace elements, Garnier says, allowing them to join together in microcavities and form rubies. “This was all a big surprise to us, and it was very interesting that we found the same petrographic characteristics in all of the deposits,” Guiliani says.

Before the collision of the Eurasian and Indian plates, lagoons or deltas sat in the regions where marble is found now. The researchers only found rubies in the places where these features had been, which, Guiliani explains, is why the gems are so rare. “The lagoon/delta and sea plus evaporation equaled evaporites,” he says, “and then add in a metamorphic event that occurred at precisely the right time and place.”

Further investigation of ruby formation, based on tectonic setting, geochemistry, fluid inclusions and isotopic ratios, allowed Giuliani’s team to develop a new model for the ruby genesis. The team hopes it will give the host countries the tools necessary to target this rare gem.

Southeast and central Asian countries have produced rubies for centuries, but research as to where and how to find more deposits is sparse, and production has slowed in recent years. Despite the rampant worldwide production of gem-quality synthetic rubies, however, the market for authentic rubies has not lessened, says Donald Olson, the gemstone commodities specialist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Companies and countries have as much incentive as ever to find new ruby deposits, he says, and “any predictive model that will help them find new deposits would be positive.”

Over the last two years, Giuliani’s team has published parts of its field research in Mineralogy and Petrology and other journals. Their model is currently under review and should be published soon, Giuliani says.