Geotimes

Feature

Geoscientists in

the Peace Corps: A Strategic Revisit

David Hastings

The Peace Corps

was founded in 1961 by John F. Kennedy and the Congressional Peace Corps Act.

Under Director Sargent Shriver, the young organization quickly garnered attention

for its dynamic and youthful (although of all ages) volunteers. The principles

of helping poor people, personal growth for volunteers and international friendship

for the United States have attracted and changed the lives of many Americans.

According to Peace Corps figures, 170,000 volunteers have served in 136 countries.

Despite occasional controversy about using citizen volunteers as instruments

of American foreign policy, the U.S. Peace Corps model spawned the creation

of similar volunteer programs around the world, including in Canada, the United

Kingdom, Sweden, France and Japan.

The Peace Corps

was founded in 1961 by John F. Kennedy and the Congressional Peace Corps Act.

Under Director Sargent Shriver, the young organization quickly garnered attention

for its dynamic and youthful (although of all ages) volunteers. The principles

of helping poor people, personal growth for volunteers and international friendship

for the United States have attracted and changed the lives of many Americans.

According to Peace Corps figures, 170,000 volunteers have served in 136 countries.

Despite occasional controversy about using citizen volunteers as instruments

of American foreign policy, the U.S. Peace Corps model spawned the creation

of similar volunteer programs around the world, including in Canada, the United

Kingdom, Sweden, France and Japan.

Van Williams, who worked with the Peace Corps in 1966 in Nepal, returned to

the country in 2003 to work with current Peace Corps volunteers on arsenic contamination.

Shown here in 2003, Williams (third from right) is working with local villagers

in Ujaini to use traditional drills to collect sediment samples from an arsenic

contaminated aquifer. Courtesy of Van Williams.

Each American president has molded the Peace Corps partly to suit his personal

vision. Early areas of emphasis were dominated by teaching and community development

activities. Small business advisors and technologists were given increased emphasis

in the Nixon administration. After the end of the Soviet Union, the Peace Corps

was adjusted to supply low-cost American assistance to restructuring efforts

in former Soviet republics.

Geoscientists, however, did not follow that trend. They were in demand from

several countries right from the beginning in the early 1960s (Geotimes,

May/June 1963). In fact, several now-prominent members of the geoscience community

began their careers in the Peace Corps — including Robert Fakundiny, the

long-term director of the New York State Geological Survey, as well as staffers

at the U.S. Geological Survey, Bureau of Land Management, Department of Energy,

National Forest Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and

NASA, as well as in industry, politics and academia.

Despite their past successful roles, geoscientists and other potentially valuable

professionals appear to be low priority in recent Peace Corps administrations.

Do geoscientists fit with the current Peace Corps?

A reunion

This question prompted a special session at last November’s Geological

Society of America (GSA) annual meeting to discuss the contribution of Peace

Corps geologists to international development and how the Peace Corps experience

has helped the development of the geosciences in America. The session also served

as a forum for assessing the current situation faced by geoscientists and like

professionals interested in serving their nation and the world through the Peace

Corps, Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO) or other such organizations.

Additionally, the event was a reunion for about 40 former volunteer geoscientists

(and some spouses).

The organizers of the session compiled a list of about 100 former Peace Corps

and CUSO volunteer geoscientists who had served in 19 countries. A questionnaire

circulated last summer received more than a dozen very detailed replies, which

are used in this article. Through generous travel support from the Kaiser Foundation,

G.O. Kesse, who is former director of the Ghana Geological Survey (1973-1993)

and a former vice president of the International Union of Geological Sciences,

was able to attend.

The Peace Corps experience

Case histories presented at the GSA meeting and elsewhere have confirmed that

most volunteers consider their experience to be one of the most important periods

of their lives. Former Peace Corps volunteer geoscientists say that almost every

imaginable circumstance has occurred. Some had their expectations exceeded with

an excellent professional match; others took a break from their originally intended

career path; still others used the experience to redefine their future career

goals.

At a minimum, the Peace Corps served as an employment agency with an umbilical

cord (in-country medical care, and the right to “bail out” early if

things were not good). Most volunteers came with only what they put in their

suitcases and were given in-country training, which sometimes, but not always,

included supplementation in the context of their professions. Much more rarely

at the other extreme, some volunteers in Ghana Geological Survey programs of

the 1960s received specialist training, vehicles, field equipment and special

allowances.

Several Peace Corps volunteers returned with a new global perspective, incorporating

international activities and concerns into their lives ever since. Others gained

positions of greater responsibility than they could have imagined before they

left home. Many volunteers saw tangible results: increased knowledge of the

geologic environment and resources of their host countries, as well as strong

professional and personal ties between themselves, the United States and host

country institutions emanating from their Peace Corps service.

Planning for the future

Sen. Norm Coleman (R-Minn.), who as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations

subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, Peace Corps and Narcotic Affairs is

influential over the Peace Corps budget, has stated that he wants greater accountability

of the Peace Corps for how it spends its funding. Most volunteers appear to

agree that the Peace Corps is doing many things well by providing fairly well-run

recruiting, application and screening procedures, training and in-country support,

at least for mainstream volunteers who, for example, teach in secondary schools.

However, if Sen. Coleman’s call for greater accountability extends to management

as well as budget, the former Peace Corps volunteer geoscientists have some

suggestions.

For the volunteer geoscientists, “accountability” may translate to

better appreciation by Peace Corps management of the diversity of the types

of volunteer positions. Many former volunteers noted that merely placing a “warm

body” with a host country agency may be inadequate, if that agency lacks

certain essentials for effective work.

Although early Peace Corps volunteers assigned to the Ghana Geological Survey

in the 1960s were well-equipped and given extensive specialist training in the

United States and Ghana, the last volunteers assigned to Ghana in the 1970s

came without such equipment and were given largely the same training as other

volunteers (minus the secondary school teacher training). It is important that

the volunteers have at least the basics to conduct their work. If the current

Peace Corps does not engage well with the concept of professionals as volunteers,

perhaps it’s time to consider another vehicle for sending volunteer geologists

abroad.

For its own support of professionals, the United States might consider models

used (at least at one time, if not at present) in other countries. Some organizations,

such as the Canadian International Development Agency and the United Nations

Development Programme placed professionals in developing country institutions

on contracts of a few years, paying them professional salaries with benefits.

Thus mid-career professionals were able to afford such work.

Some countries, for example the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, had salary

supplementation schemes, such as the British Expatriates Supplementation Scheme

(BESS). Under this program, professionals would apply for normally advertised

vacancies, such as for teaching faculty of a university in a developing country,

a national geological survey or forestry department. If accepted, BESS offered

salary supplementation and other benefits to enable the professionals to afford

working in the developing country and still be able to retire back home.

Such avenues lack certain aspects of the “Peace Corps experience.”

But a variation on such a program might be worth considering if the Peace Corps

cannot adequately respond to concerns about professionals as volunteers.

A new bureaucratic body need not necessarily be created. Perhaps a U.S. funding

agency and a contractor (such as a consortium of universities) could fund and

administer the program. Perhaps Michigan Technological University’s master’s

degree program using Peace Corps service could be extended to Ph.D. or non-degree

research and development. Perhaps the Peace Corps could be the contractor for

the recruitment and in-country support of such volunteers, with a consortium

of agencies handling the extra support to make such volunteers more effective.

Additionally, the Peace Corps process could be improved both at the recruitment

end and for when the volunteers go home. During recruitment, communication could

be stronger: A former volunteer (who wishes to remain anonymous) recalls the

Peace Corps painting a very gloomy picture of working conditions at a university

in which he was to be placed. After reading that the university had virtually

no equipment in the labs and few books or journals in the library, the apprehensive

volunteer was able to convince the Peace Corps to pay to ship his library of

professional books and journals to his job site.

To his pleasant surprise, the volunteer found a fairly well stocked library

and well-equipped laboratories upon his arrival. To top things off, nearby governmental

institutions had additional field equipment available for loan if he worked

cooperatively with them. He wound up extending his tour modestly to help a master’s

degree student complete his studies, then returned to the country later to work

for three invaluable years. Now 30 years later, he is grateful that he was not

put off by that unnecessarily gloomy description by the Peace Corps.

On the return end, most volunteers have experienced some challenges in adjusting

to life back in the United States (see sidebar). This

may be even tougher for any possible present-day Peace Corps volunteer geoscientists

who plan to enter the job market immediately after return, rather than going

back to campus. Between the tight job market for geoscientists and other factors

encountered by many volunteers, more support might be worthwhile.

To that end, former geoscience volunteers suggested creating an optional workshop

covering topics common to returning volunteers. These could be held several

times a year, in locations where returned Peace Corps volunteers tend to congregate.

The Peace Corps currently offers limited counseling facilities for returned

volunteers.

At November’s gathering, the retired Peace Corps volunteer geoscientists

agreed that the Peace Corps, or other similar national volunteer organizations,

can provide unique opportunities for geoscientists and other professionals.

However, as the Peace Corps passes into middle age, it is time to reevaluate

some of its features and history, seeking to refine management to better handle

professionals in its ranks. Many ideas for professional service sit on the shelf

from past Peace Corps efforts, along with those of other volunteer and foreign

assistance organizations. If the Peace Corps does not address such issues, perhaps

an alternative structure can better support professionals in voluntary service.

| An

American geologist in Tanzania

From 1964 to 1966, Eleanora (Norrie) Iberall Robbins served as a Peace

Corps volunteer with the Tanzania Geological Survey (TGS), immediately

following receipt of her bachelor’s degree from Ohio State University.

Stationed in Dodoma in the days before computers, her assignment was to

search anomalous values in notebooks of stream sediment geochemical data

taken by Williamson’s Diamonds.

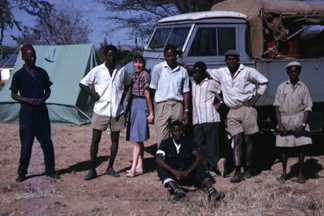

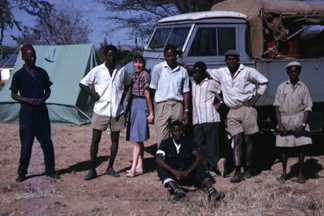

Eleanora

(Norrie) Iberall Robbins leaves with crew for field work in Kondoa, Tanzania,

in 1965.Courtesy of Norrie Robbins. Eleanora

(Norrie) Iberall Robbins leaves with crew for field work in Kondoa, Tanzania,

in 1965.Courtesy of Norrie Robbins.

“None of the men at TGS wanted the job,” Robbins recalls, “so

the survey decided this would be a perfect assignment for a female Peace

Corps geologist.” She became the first woman sent out in charge of

a field party. And for her vacation, Robbins volunteered for Louis Leakey,

mapping the Olorgesailie hand-axe site in the Great Rift Valley in Kenya.

Successful Peace Corps service, Robbins says, gave her noncompetitive

eligibility for a U.S. government job; she was hired by the U.S. Geological

Survey (USGS) in 1967 based on her foreign experience. One assignment

at USGS focused on the economic deposits in the Early Mesozoic (rift)

basins of the eastern United States. Robbins was able to apply insights

from her Peace Corps mapping in the Great Rift Valley of Kenya to the

coal, petroleum and mineral deposits of Virginia and North Carolina.

Through correspondence with Philip Momburi, a current geologist at TGS

in Dodoma, she continued pursuing her “lifelong interest in trace

metals in the environment.” Momburi is researching human bioaccumulation

of deleterious trace elements.

Now retired from the USGS and serving as adjunct faculty at San Diego

State University, Robbins teamed up with Momburi to present their work

at last November’s Geological Society of America meeting in Seattle,

as part of a session on the emerging field of geology and human health.

|

Making

an impact in Bulgaria

Jake Cinnamon spent his Peace Corps experience living in a small town called

Omurtag in Bulgaria, and working as an environmental consultant. Cinnamon,

age 27, has a degree in geology from the University of Colorado, but he

“never used it much,” he says. “I went directly into the Peace Corps.”

Jake

Cinnamon lectures ninth-grade students in Panagyurishte, Bulgaria, on structural

geology during his recent Peace Corps service. Courtesy of Jake Cinnamon. Jake

Cinnamon lectures ninth-grade students in Panagyurishte, Bulgaria, on structural

geology during his recent Peace Corps service. Courtesy of Jake Cinnamon.

Starting in the summer of 2001, Cinnamon worked on a variety of basic environmental

programs, including energy efficiency and choosing new street lights for

the town. He had the opportunity to discuss environmental impacts of mining

with local geologists who were exploring sites in the region, and he says

he also worked on issues for a cheese factory that “spit out enzymes into

the river — one of my jobs was to figure out how to clean it up.”

Cinnamon also worked on non-geology-related projects. He wrote grants for

a local school, capturing $15,000 to buy three new computers and a digital

camera, and he arranged for Internet access. “These kids had never seen

the Internet before,” he says.

Since Cinnamon returned to the United States last August, he has been unsure

if he wants to pursue geology as a career — a common challenge facing

returning volunteers. Instead, he is looking into working with geographic

information systems and government relations, or what he calls “the business

side of geology.” |

Hastings works for the United

Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific in Bangkok, Thailand.

He served in the Peace Corps from 1972 to 1974 in Ghana. After leaving the Peace

Corps, he joined the Ghana Geological Survey until 1978, and then worked in the

United States until 2002.

This article is based on many of the opinions expressed at the Geological Society

of America meeting last November, during a session about geologists in the Peace

Corps, organized by Robert A. Levich, R. Stephen Saunders, Ernest W. Kendall and

others.

Back to top

The Peace Corps

was founded in 1961 by John F. Kennedy and the Congressional Peace Corps Act.

Under Director Sargent Shriver, the young organization quickly garnered attention

for its dynamic and youthful (although of all ages) volunteers. The principles

of helping poor people, personal growth for volunteers and international friendship

for the United States have attracted and changed the lives of many Americans.

According to Peace Corps figures, 170,000 volunteers have served in 136 countries.

Despite occasional controversy about using citizen volunteers as instruments

of American foreign policy, the U.S. Peace Corps model spawned the creation

of similar volunteer programs around the world, including in Canada, the United

Kingdom, Sweden, France and Japan.

The Peace Corps

was founded in 1961 by John F. Kennedy and the Congressional Peace Corps Act.

Under Director Sargent Shriver, the young organization quickly garnered attention

for its dynamic and youthful (although of all ages) volunteers. The principles

of helping poor people, personal growth for volunteers and international friendship

for the United States have attracted and changed the lives of many Americans.

According to Peace Corps figures, 170,000 volunteers have served in 136 countries.

Despite occasional controversy about using citizen volunteers as instruments

of American foreign policy, the U.S. Peace Corps model spawned the creation

of similar volunteer programs around the world, including in Canada, the United

Kingdom, Sweden, France and Japan.

Eleanora

(Norrie) Iberall Robbins leaves with crew for field work in Kondoa, Tanzania,

in 1965.Courtesy of Norrie Robbins.

Eleanora

(Norrie) Iberall Robbins leaves with crew for field work in Kondoa, Tanzania,

in 1965.Courtesy of Norrie Robbins. Jake

Cinnamon lectures ninth-grade students in Panagyurishte, Bulgaria, on structural

geology during his recent Peace Corps service. Courtesy of Jake Cinnamon.

Jake

Cinnamon lectures ninth-grade students in Panagyurishte, Bulgaria, on structural

geology during his recent Peace Corps service. Courtesy of Jake Cinnamon.