Geotimes

Untitled Document

Feature

What Makes Good

Climates Go Bad?

Michael Glantz

While

playing tennis one sunny afternoon, I began wondering the following: What is

it that makes good climates go bad? That random question passing through my

mind sparked another question: What does it mean to have a “good”

climate? So, I resorted to a Google search on the phrase “good climate.”

In fact the search identified many Web sites with “good climate” in

their text. However, the climate they were referring to almost totally was the

atmosphere for carrying out a good business arrangement — a “good

climate” for studying, working and conducting wide range of activities.

But “climate” specifically is the appropriate environment that allows

for the carrying out of favored activities.

While

playing tennis one sunny afternoon, I began wondering the following: What is

it that makes good climates go bad? That random question passing through my

mind sparked another question: What does it mean to have a “good”

climate? So, I resorted to a Google search on the phrase “good climate.”

In fact the search identified many Web sites with “good climate” in

their text. However, the climate they were referring to almost totally was the

atmosphere for carrying out a good business arrangement — a “good

climate” for studying, working and conducting wide range of activities.

But “climate” specifically is the appropriate environment that allows

for the carrying out of favored activities.

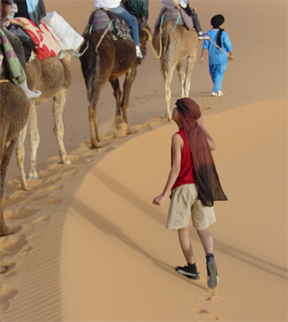

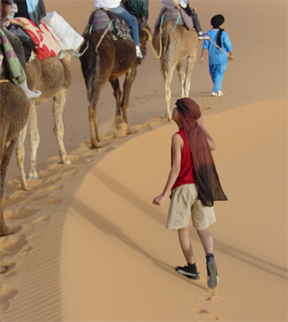

What constitutes good climate is different

to people in different places. Some people are acclimated to the cold Arctic.

Others prefer the hot humid rainforest, such as the jungles in the Peruvian

Amazon. Yet others may live in hot, dry desert climates, like the nomad shown

here traveling along sand dunes of the Sahara Desert, near Erfoud in southern

Morocco. Copyright of AGI.

Eskimos live in cold climate conditions; desert nomads live in hot dry climates;

people in tropical rainforests live in what many people in other ecosystems

would call oppressive humidity and sweltering heat. These populations in their

respective climate regimes may consider their environments to be “good

climate,” but each is very different. And most likely, it would not be

possible to encourage any group to move to the others’ climate setting.

American longshoreman-philosopher Eric Hoffer wrote in his 1963 book Ordeal

of Change about how people fear change. Our grandparents lived through harsh

winters and hot summers, usually without the benefits of heat or air conditioning.

They just did it. Today, we have milder winters and not-so-bad summers. We also

have all the accoutrements of an affluent industrialized society. We wouldn’t

think of moving to a home in Arizona with no air conditioning or to a cabin

in Maine with no heat.

Anything that changes our daily climates would likely cause or will be perceived

as a problem because it would mean we would eventually have to change our behavior

in ways we don’t really know. So arguably, perceptible changes are general

examples of a climate “going bad.” Less rain or more rain for crops,

depending on location, activities and crop type, could also signal a climate

going bad, as could cloudier days, sunnier days, drier days or more humid days

for someone or some activity.

What, then, is a bad climate? It is one in which individuals and ecosystems,

including human settlements, are unable to survive in a sustainable way over

a long period of time. While some individuals may have the fortitude and economic

well-being to move to a more favorable climate, most people do not have that

option. They have to live under the climate regime into which they were born.

To them, the idea of a “good climate” or a “bad climate”

is irrelevant. They live in a tolerable climate, one to which their expectations

and their behavior have become accustomed.

So, there may be climate regimes under which we would like to live and those

under which we do live and tolerate. Visiting a perceived “ideal”

climate is one thing; living in it forever is another. American novelist John

Steinbeck once wrote, “I’ve lived in good climate and it bores the

hell out of me. I like weather rather than climate.”

While we can question what it means to have a good, bad or tolerable climate,

there are real characteristics of a climate that can be measured — temperature,

precipitation, humidity, etc. — and matched to appropriate human activities.

Those characteristics can change at different rates in different locations.

Whether or not humans can adjust to those rates and changes without disruption

will vary from place to place, and from time to time, even in the same place.

The notion of adaptation has now crept into discussions in the past two and

a half decades about global warming (and before then, a decade of talk about

global cooling). At first, discussions centered at the international level on

prevention of those factors that are enhancing the naturally occurring greenhouse

effect. Given the apparent inability of the international community to work

together to freeze the global climate regime the way it is today (which, by

the way, is favorable to some, unfavorable to others and only tolerable to yet

others), “adaptation” became the buzz word.

Prevention versus adaptation frames societal responses as being only black and

white, positive or negative, all or nothing. There are other types of societal

responses, the ones that individuals and societies engage in all the time, so

simple as to be overlooked: adjustment, acclimatization, becoming accustomed

to.

In thinking about our potential responses, however, it is also useful to think

about what shapes our climate. There are many geophysical reasons — including

Earth’s orbit, solar activity, continental drift and volcanism — why

good climates go bad. Such reasons seem to get the lion’s share of the

public’s attention. But perhaps societies and their leaders are all too

eager to blame something or someone else for the damages (death, sickness, misery

and destruction) caused by those anomalies. Human activities from a local to

a national scale can affect the climate regimes under which people operate.

For example, scientists have identified human influences on the climate and

weather of metropolitan areas. They have labeled the results of this influence

as the “urban heat island” effect: The concrete and asphalt surfaces

that dominate metropolitan areas, along with the widespread use of fossil fuels

(coal, oil, natural gas), as well as innumerable heating and cooling systems

in high concentration, has led to the heating up of an invisible bubble of warm

air that encompasses urban areas.

This example shows people altering the climate in the place where they have

chosen to settle. In addition, the heat island can also influence precipitation

within the bubble, with storms, for example, dropping more moisture on metropolitan

areas. The heat island also has impacts downwind in suburban and rural areas,

apparently by increasing precipitation in those areas.

Human activities have also led to major changes in regional climate regimes.

One example of the “foreseeability” of such an impact can be found

in the Amazon basin of South America. Deforestation rates in the basin are quite

high, and cutting down the forest reduces, at an admittedly incremental but

cumulative pace, the rainforest’s effectiveness as a sink for atmospheric

carbon dioxide. Burning the rainforest creates a source of carbon dioxide as

well.

Of more immediate concern, though, is that researchers have found that about

half of the rain that falls in the Amazon basin comes from the rainforest itself

in a self-perpetuating water recycling process. Cutting down trees in the forest

chips away at the amount of precipitation that can be expected to fall within

the basin. This process eventually reduces soil moisture, river-flow quantity

and quality, and even human habitability in the region in ways that can already

be seen around the globe on small scales.

Another

example of regional climate change induced as a result of human activities is

the changing Aral Sea in Central Asia. The Aral Sea was the fourth largest inland

sea in the world as of 1960. Today, it has dropped more than 22 meters and has

separated into two separate seas. Its demise is directly attributable to political

decisions to divert water from the basin’s two major rivers that feed the

sea, and to put that river water on dry but potentially fertile desert soils.

Studies now show that as a result of the desiccation of the Aral Sea and the

resulting increase in exposure of large expanses of the sandy seabed (a change

in land surface reflectivity), the region’s winters have gotten colder

and the summers hotter.

Another

example of regional climate change induced as a result of human activities is

the changing Aral Sea in Central Asia. The Aral Sea was the fourth largest inland

sea in the world as of 1960. Today, it has dropped more than 22 meters and has

separated into two separate seas. Its demise is directly attributable to political

decisions to divert water from the basin’s two major rivers that feed the

sea, and to put that river water on dry but potentially fertile desert soils.

Studies now show that as a result of the desiccation of the Aral Sea and the

resulting increase in exposure of large expanses of the sandy seabed (a change

in land surface reflectivity), the region’s winters have gotten colder

and the summers hotter.

Once the fourth largest lake on Earth,

the Aral Sea moderated Central Asia’s continental climate and supported

a productive fishing industry. It has shrunk dramatically over the past few

decades, as people have diverted the primary rivers that fed the sea for cotton

farming and other agriculture. Landsat satellite imagery (left image) shows

that the northern and southern half of the sea had already become virtually

separated by 1989. The image at right was captured by the Moderate Resolution

Imaging Spectroradiometer on the Aqua satellite on Aug. 12, 2003, and shows

the rapid retreat of the sea’s southern half, now separated into western

and eastern portions. Courtesy of NASA and the University of Maryland Global

Land Cover Facility.

Books have been written about how civilizations have misused their land by deforesting,

over-cultivating, over-irrigating or overgrazing vulnerable ecosystems. North

Africa, for example, was once the granary of the Roman Empire. Some historians

blame the current desert landscape along the southern Mediterranean on deforestation

and on poor land-use practices for cultivation. Others blame it on a major natural

change to the region’s climate regime. Most likely, both were contributing

factors — but in what proportion?

There is also a general belief — some say blind faith — that what

people have done that is bad for the environment or climate, they can undo.

All it will take is engineering know-how and technological innovation. As a

result, throughout history there have been attempts to restore changed climate

conditions to their original state. Climate modification schemes have been proposed

to bring rainfall, for example, back to arid lands where it had once fallen.

The planting of trees has been a popular idea, fostered by European foresters

to bring rain back. Others have hypothesized that rainfall tends to “follow

the plow,” for example, responding to cultivation practices, as well as

tree planting and settlements.

That brings us to the topic of the day (or topic of the century) — global

warming. I do believe that the byproduct of human activities can alter the chemistry

of Earth’s atmosphere in ways that will slowly but profoundly affect societies

worldwide. The emission of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide,

methane and various types of CFCs) to the atmosphere in ever increasing amounts

since the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-1700s has enhanced the

naturally occurring greenhouse effect. The consequence has been the warming

up of the global average temperature by 0.7 degrees Celsius since the beginning

of the 1900s.

While there is controversy over various scientific aspects of the global warming

phenomenon (is it human-induced or is it a natural occurrence?), evidence has

been mounting over the past several decades that human activities are at play

in the heating up of the relatively thin atmosphere that shrouds planet Earth.

But societal leaders and citizens are always on a slippery slope, living within

the bounds of the climate conditions that they have inherited from their predecessors

as well as having to anticipate future variations. Those leaders have to make

decisions about future demands as well as present-day needs for water, energy,

food, public health and safety. They are constantly forced to do so in the absence

of full knowledge of future climate conditions in other locations as well as

their own.

We know that climate varies naturally on a range of time scales from months

to years, decades, centuries and millennia. We need to understand the causes

and effects of those extremes (highs and lows) in variability of temperature

and rainfall; we need to juggle their activities against recurrent but aperiodic

droughts, floods, severe storms and fires, and against quasi-periodic episodes

of El Niño and La Niña.

However, armed only with hazy insights into the future and scientific information

with varying degrees of uncertainty, we end up tracking the climate variability

curves and twists imperfectly. As a result, actions are often taken that prove

to have been inappropriate for any particular unexpected climate anomaly.

Much of this is known. At least at a general level, we are familiar with the

natural factors that affect the planet’s atmospheric composition and behavior

— our climate. We are also becoming increasingly familiar with the actions

that societies take that harm the environment, including the chemistry of the

atmosphere, thereby affecting climate. What seems to have been neglected is

what constitutes a good, bad or tolerable climate.

When we talk of climate change, is it that we fear change — any change

— to the local or global climate conditions to which we have become accustomed?

Or, on a more positive note, is it that we (from Inuit in the Arctic to Tuareg

in the Sahara) consider the climate we have as a “good” climate worthy

of preservation for as long as possible? To what extent do societal climate

preferences match individual climate preferences?

These are important questions to address, as we now know for sure that climates

are constantly changing in both linear and nonlinear ways and that over the

course of life on Earth, organisms have either adjusted to those changes or

perished.

Glantz is a senior scientist

at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. E-mail: glantz@ucar.edu.

Back to top

While

playing tennis one sunny afternoon, I began wondering the following: What is

it that makes good climates go bad? That random question passing through my

mind sparked another question: What does it mean to have a “good”

climate? So, I resorted to a Google search on the phrase “good climate.”

In fact the search identified many Web sites with “good climate” in

their text. However, the climate they were referring to almost totally was the

atmosphere for carrying out a good business arrangement — a “good

climate” for studying, working and conducting wide range of activities.

But “climate” specifically is the appropriate environment that allows

for the carrying out of favored activities.

While

playing tennis one sunny afternoon, I began wondering the following: What is

it that makes good climates go bad? That random question passing through my

mind sparked another question: What does it mean to have a “good”

climate? So, I resorted to a Google search on the phrase “good climate.”

In fact the search identified many Web sites with “good climate” in

their text. However, the climate they were referring to almost totally was the

atmosphere for carrying out a good business arrangement — a “good

climate” for studying, working and conducting wide range of activities.

But “climate” specifically is the appropriate environment that allows

for the carrying out of favored activities.

Another

example of regional climate change induced as a result of human activities is

the changing Aral Sea in Central Asia. The Aral Sea was the fourth largest inland

sea in the world as of 1960. Today, it has dropped more than 22 meters and has

separated into two separate seas. Its demise is directly attributable to political

decisions to divert water from the basin’s two major rivers that feed the

sea, and to put that river water on dry but potentially fertile desert soils.

Studies now show that as a result of the desiccation of the Aral Sea and the

resulting increase in exposure of large expanses of the sandy seabed (a change

in land surface reflectivity), the region’s winters have gotten colder

and the summers hotter.

Another

example of regional climate change induced as a result of human activities is

the changing Aral Sea in Central Asia. The Aral Sea was the fourth largest inland

sea in the world as of 1960. Today, it has dropped more than 22 meters and has

separated into two separate seas. Its demise is directly attributable to political

decisions to divert water from the basin’s two major rivers that feed the

sea, and to put that river water on dry but potentially fertile desert soils.

Studies now show that as a result of the desiccation of the Aral Sea and the

resulting increase in exposure of large expanses of the sandy seabed (a change

in land surface reflectivity), the region’s winters have gotten colder

and the summers hotter.