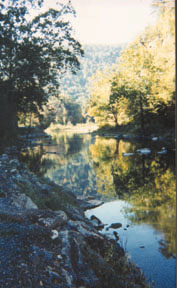

When clear cutting was a common agri-

cultural practice 150 years ago, many

forested regions on the East Coast were

not as lush as they are today. In recent

decades reforestation has played a

major role as a carbon sink in the eastern

United States. Photo taken east of

Elkins, W.Va. Photo by Kristina Bartlett,

Geotimes.

Of the 7 billion tons of carbon emitted into the atmosphere each year, half stays in the atmosphere. Of the other half, some is stored in the ocean and the rest is stored on land. Carbon-cycle scientists are looking at a variety of mechanisms working in concert to remove carbon from the atmosphere. But they are left with many questions about the processes involved and their implications for global sustainability, especially in regard to terrestrial mechanisms. At the spring meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington, Field and other scientists met to discuss the important role that carbon-cycle science plays in achieving global sustainability.

To understand the carbon cycle, scientists need to look at all aspects of the Earth system from hydrologic and climatic dynamics to ecological systems. Using eddy flux technology — a mechanism by which carbon can be measured in the atmosphere at different locations above a forest canopy — Steve Wofsy of Harvard University works to quantify the amount of carbon stored in the Harvard Forest in Massachusetts. Wofsy is co-chair of the Carbon and Climate Working Group of the U.S. Global Change Research Program in Washington, and he and many others believe something is missing in scientists’ understanding of the terrestrial sinks. Measuring atmospheric carbon dioxide over forested regions and tallying forest mass allow scientists to estimate carbon accumulation on land. “But there is a missing sink not on the books,” Wofsy says.