Mars may hide shades of blue

June 22, WASHINGTON

While searching for the lost Polar Lander

last year, a camera on NASA’s orbiting spacecraft Mars Global Surveyor

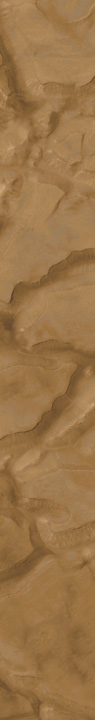

shot close-up images of seepage and runoff along the walls of martian pits,

craters and valleys. The fan-shaped rivulets have shocked scientists with

the idea that pockets of liquid water may still lie buried close to the

surface, a discovery that may revolutionize modern theories about Mars

and change the priorities of future missions.

“Actual observations pale to science fiction written,” said Mike Malin of Malin Space Science Systems, which designed the Mars Orbiter Camera. He announced his team’s findings today at a news conference at NASA headquarters. The photos set a precedent for their detail, capturing gullies “you could walk across” in a few minutes, he said.

After two years of skimming through Mars’ thin upper atmosphere on an elliptical path, Mars Global Surveyor finally slowed to a circular polar orbit last year. Once in focus, its camera zoomed in on martian landmarks like a tourist at Disneyland, providing about a hundred pictures a day. So far, more than 250 images of the 65,000 taken have shown features that look like mudflows.

“If these had been on Earth there would be no question that water was involved,” Malin said. The gullies and channels share strong resemblance to many water-worn landmarks on Earth — such as the water trails that percolated through the ash on Mount St. Helens, deltas on the Mississippi, desert flashfloods, and glacier outbursts or jökulhlaups. One gully named the “Weeping Layer,” located on the south-facing wall of a trough in the Gorgonum Chaos region, resembles the rainwater that trickles down the cliffs at “Weeping Rock” in Utah’s Zion National Park on the edge of the Colorado Plateau.

But unique to Mars, the features share a peculiar habit of growing like moss in areas facing away from the sun. They also tend to appear in clusters located outside the equatorial region, such as Gorgonum Chaos, Vallis Nirgal and Dao Vallis, mostly between 30 and 70 degrees latitude in both hemispheres. “My confidence was severely shaken by this discovery,” Malin said. “I couldn’t put it into context with the understanding I’ve gained from working on Mars for the past 30 years.”

Although the red planet is known to harbor water locked up as ice at its poles and as vapor in the atmosphere, scientists considered the martian surface mostly too cold for liquid water. They thought water only had a chance of existing as liquid beneath the heated rocks of the equator.

Malin and colleague Ken Edgett, who selected the imaging targets for the Mars Orbiter Camera, reported their discovery in the June 30 Science. Taking into consideration the landmarks’ relationship to sunlight and latitude, they hypothesized that water might exist in reservoirs around the planet but evaporate on contact with the surface.