geotimesheader

News

Notes

Science

Policy

Evasive

nuclear testing a misstated threat

Keeping nuclear tests a secret is difficult, say researchers who argue

that Senate leaders resorted to political stealth and misleading claims

about verification during last October’s debate over ratifying the Comprehensive

Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. One of the points of contention that has dogged

the treaty for 40 years, and some scientists say should be put to sleep,

has been the credibility of monitoring for evasive tests.

The international treaty would ban testing of nuclear weapons. During

last year’s debate, when the Senate failed to ratify the treaty, the majority

believed countries other than the United States might be capable of modernizing

their nuclear weapons through clandestine testing.

“It is possible to conduct a nuclear test with the intention of evading

systems designed to detect the explosion’s telltale seismic signature,”

said Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott on Oct. 8, 1999. Lott argued that

the U.S. government’s Arms Control Intelligence Staff considered caverns

dug in hard rock salt places where tests would be muffled to the outside

world — a technique known as decoupling or, more simply, the big-hole technique.

“Claims in the Senate debate about decoupling were either false or greatly

exaggerated,” says seismologist Lynn Sykes of Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory.

Sykes and others presented their views May 31 at the spring meeting of

the American Geophysical Union.

Sykes compared the debate last year with the zeal surrounding decoupling

during the 1960s when Eisenhower’s first science advisor, James Killian,

stated in his memoirs: “The big-hole technique proved to be much more difficult

than expected by its advocates. … It was a bizarre concept, contrived as

part of a campaign to oppose any test ban.”

In 1964, a 5.3-kiloton test created a cavity 828 meters deep with a

mean radius of 16.7 meters in the Hattisberg, Miss., salt deposits. Two

years later, the crater buffered a 0.38-kiloton explosion code named the

“Sterling” test. The Sterling test remains as the only known successful

and fully decoupled nuclear explosion, Sykes says.

A one-kiloton explosion has as many calories of energy as 1,000 tons

of TNT and generates the equivalent of a magnitude-4 earthquake, says Greg

van der Vink of the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS)

Consortium in Washington. “Less than 1 percent of the energy from a bomb

is transformed into seismic waves,” he says. “Mostly it turns into heat

that vaporizes into the air and melts rock. Relatively little is actually

generating a seismic wave.”

| To fully cloak a nuclear test from the International Monitoring System,

a cavity needs to keep radionuclides from escaping, dampen the seismic

waves and cushion the shock waves without overstressing the rock. With

all its cracks and deformation, hard rock is simply not up to the job,

Sykes says. But hydrologic mining of salt could pump out brine and create

a large cavern with no cracks or joints. Still, it would be difficult to

keep secret, he says.

It’s no small task: A five-kiloton explosion in salt would require a

cavity 43 meters in diameter, big enough to fit the Statue of Liberty.

Most of the land in India and Pakistan is too dry for solution mining and

disposal of brine in rivers can easily be detected by satellite images.

And less than 1 percent of the land in Russia has salt, Sykes says.

Still, politicians express concern that five- to 10-kiloton testing

could be muffled in cavities in Russia or China and made to look like smaller

explosions, or even masked entirely. Should that ever occur, “it would

indicate they’re engaging in nuclear modernization and we’re not,” a senior

staff member on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who asked not to

be named, said at a recent Washington meeting.

Modernizing nuclear weapons vs. continuing with the ban on testing that

President George Bush initiated in 1992 is emerging as an underlying part

of the debate. The crux rests on whether or not the United States can maintain

its stockpile in working condition without testing. “We have encountered

problems we would have tested for in the past,” the staff member

said. “We would need to resume testing if problems reach above a certain

threshold, but to date those problems have not been identified. Will we

reach that threshold in the next administration? I believe we probably

will.” |

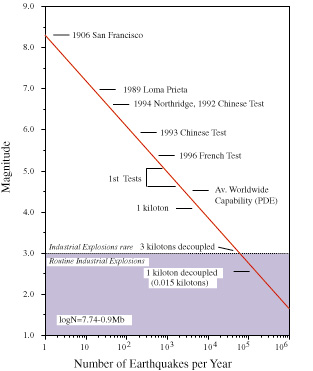

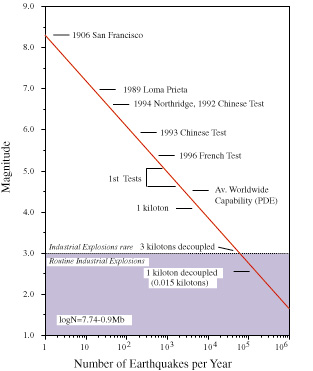

Seismic monitoring becomes more difficult as the size of the

explosion decreases. At lower magnitudes more earthquakes

occur, as do more legitimate industrial explosions, more

credible evasion scenarios and higher levels of naturally

occurring background noise. (PDE is the Preliminary

Determination of Epicenters, published by the U.S.

Geological Survey.) Greg van der Vink, IRIS. |

Christina Reed