The

Antarctic ice sheet stores 90 percent of Earth’s frozen freshwater. Its

freezing and melting dynamics have many implications for climate change. Now,

scientists Eric Rignot from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Stanley

Jacobs from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory reveal

in the June 14 issue of Science that the bottoms of Antarctic ice shelves are

melting more rapidly at their grounding lines — where ice detaches from

the seafloor and begins to float — than previously thought.

The

Antarctic ice sheet stores 90 percent of Earth’s frozen freshwater. Its

freezing and melting dynamics have many implications for climate change. Now,

scientists Eric Rignot from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Stanley

Jacobs from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory reveal

in the June 14 issue of Science that the bottoms of Antarctic ice shelves are

melting more rapidly at their grounding lines — where ice detaches from

the seafloor and begins to float — than previously thought. “It’s important because in the climate machine, which includes interactions among ice, atmosphere and oceans, the component that has been overlooked is ocean-ice interaction,” says Terence Hughes, glaciologist at the Institute of Quaternary and Climate Studies at the University of Maine. “Using satellite data, a means that has revolutionized the science, the authors better constrain an important and extremely vulnerable part of the climate system, the ice sheets.”

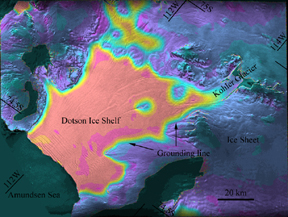

Image of tidal motion of Dotson Ice Shelf, Antarctica, obtained from interferometric synthetic-aperture radar data. Grounded ice is blue, floating ice is red, the transition from grounded to floating ice is blue, to light green, to yellow and red as the ice adjusts to hydrostatic equilibrium. Image size: 100 kilometers by 100 kilometers,from the European Remote Sensing Satellite ERS-1; Taken in 1992.

Satellite radar interferometry, a technique that measures the change in size, velocity and shape of an object, helped precisely locate the grounding lines of 23 ice shelves extending from ice sheets.

Depths at which ice shelves detach from the seafloor vary. The ocean water is 2 to 3 degrees above freezing and, due to its saline composition, is able to melt the ice. At depth, increasing pressure causes greater melting.

Although the authors suggest that melt rates maintain the equilibrium of the Antarctic ice sheet, they estimate that a 0.1 degree Celsius increase in ocean temperatures will lead to melt increases of a meter per year. “A change of 0.1 degree Celsius is not unrealistic, and a meter per year thinning of ice is a large rate. In a hundred years an ice shelf can disappear,” Rignot says.

Hughes agrees. “This research does change the way we consider the Antarctic ice sheet. We are getting at the underlying mechanism that causes ice sheets to melt and we see that this melting is happening very quickly.”

Salma Monani