When it comes

to the mass extinction that marked the Cretaceous/Tertiary (K/T) boundary 65

million years ago, most people want to know what killed the dinosaurs. A new

study instead focuses not on who died, but on who survived and why. What it

all came down to, researchers say, is that only those who hid had a chance to

survive.

When it comes

to the mass extinction that marked the Cretaceous/Tertiary (K/T) boundary 65

million years ago, most people want to know what killed the dinosaurs. A new

study instead focuses not on who died, but on who survived and why. What it

all came down to, researchers say, is that only those who hid had a chance to

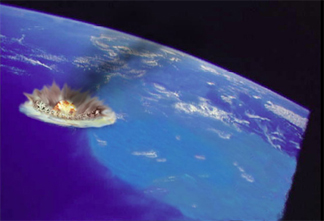

survive.An artist’s illustration shows the impact at the Chicxulub crater site off the Yucatan Peninsula 65 million years ago, which many researchers have linked to a global mass extinction. Some scientists now say that the event’s surviving land animals were those who burrowed out of harm’s way. Image courtesy NASA/University of Arizona Space Imagery Center.

Douglas Robertson, a geophysicist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and his co-authors, including paleontologists specializing in mammals and birds, base their study on the idea that an intense atmospheric heat pulse caused by the reentry of ejected impact debris would have heated the sky for several hours and ignited global wildfires. This fiery environment would have killed off most species in a geological instant and reset the course of future evolution, they write, unless the animals were able to seek shelter.

“We argue that sheltering underground, within natural cavities or in water was the fundamental means of survival during the first few hours of the Cenozoic,” the authors write in the May/June issue of the Geological Society of America Bulletin. The idea of burrowers or swimmers being able to survive an intense heat event is not new. But “the thing that is novel here,” Robertson says, “is that nobody else noticed that the question of what is underground or underwater provides a very good match to the observed survival patterns of land animals.”

Because the model assumes the occurrence of global wildfires, the paper has reignited the controversy over the amount of heat generated by the impact and whether wildfires engulfed the globe following it. Most scientists now agree that an impact occurred at the Chicxulub crater discovered off Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula, and that the impact would have caused ejecta and therefore some degree of thermal radiation upon the re-entry of that ejecta into the atmosphere. They continue to debate, however, the thermal fallout as well as the impact’s other environmental effects, and whether those events caused a gradual or sudden extinction.

“The effect of the impact, the universality of it and the amount of energy that returned to Earth are still open to debate,” says Arthur Sweet, a palynologist with the Geological Survey of Canada in Calgary, Alberta. Sweet has found well-preserved, uncharred pollen samples across the K/T boundary, and he discovered that pollen assemblages were changing well before the boundary, which he says is why he falls into the multiple-factor camp.

Additionally, Sweet co-authored a recent paper that found less-than-normal background levels of charcoal in various K/T boundary layer sites across North America — evidence, the authors said, of the lack of global wildfires. Robertson’s team, however, says that the lack of charcoal would be expected because the fires would have been intense enough to burn it completely.

The new study addresses only terrestrial extinctions, not the extensive marine ones. Robertson’s team says that one factor in whether land animals survived was their body size, noting that the mammals surviving the K/T were the size of a rat or smaller (larger mammals did not evolve until hundreds of thousands to millions of years later). “If they were rat-sized or smaller, they were plausibly burrowers,” Robertson says.

Some researchers, however, question the accuracy of this premise. Bill Clemens, a paleontologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who specializes in early mammals, says that the size range of many early marsupials was similar to that of early placental mammals, yet the marsupials did not survive. “To me that suggests that selectivity here really isn’t explained,” Clemens says.

In theory, everything alive today will have descended from a sheltering organism — including birds, which, the authors say, would have had to burrow or, once singed, been able to find immediate respite in water, a scenario Clemens finds dubious. “That part of their article just struck me as really improbable,” he says.

Robertson acknowledges that birds are a problematic case, but notes that many kinds of birds today nest in burrows, or swim or dive. He points out that the theory offers even those that sought shelter only a very small probability of surviving the impact. “We think that all of the non-shelterers died and probably most of the shelterers did too,” he says. “This thing was awful.”

If an organism did survive, he says, species fitness would have dropped drastically because the environment to which they were adapted was now gone; the new one was possibly in the throes of an impact winter, lacking adequate food and sunlight.

Robertson says their theory doesn’t address how many dinosaurs were still around to suffer the consequences of the impact, a nod toward theories that dinosaurs were in gradual decline up to the K/T boundary or extinct long before it. However, he says, “any of them that were still present would have become extinct in hours.”