Geotimes

Untitled Document

Web Extra

Thursday, August 5, 2004

Whale-bone-eating worms

In Monterey Bay, off the coast

of California, researchers have discovered a group of extraordinary marine worms

that feed on the bones of dead whales. Even Jules Verne would have difficulty

imagining up these creatures whose closest relative may be the tubeworms found

at deep-sea vents.

In Monterey Bay, off the coast

of California, researchers have discovered a group of extraordinary marine worms

that feed on the bones of dead whales. Even Jules Verne would have difficulty

imagining up these creatures whose closest relative may be the tubeworms found

at deep-sea vents.

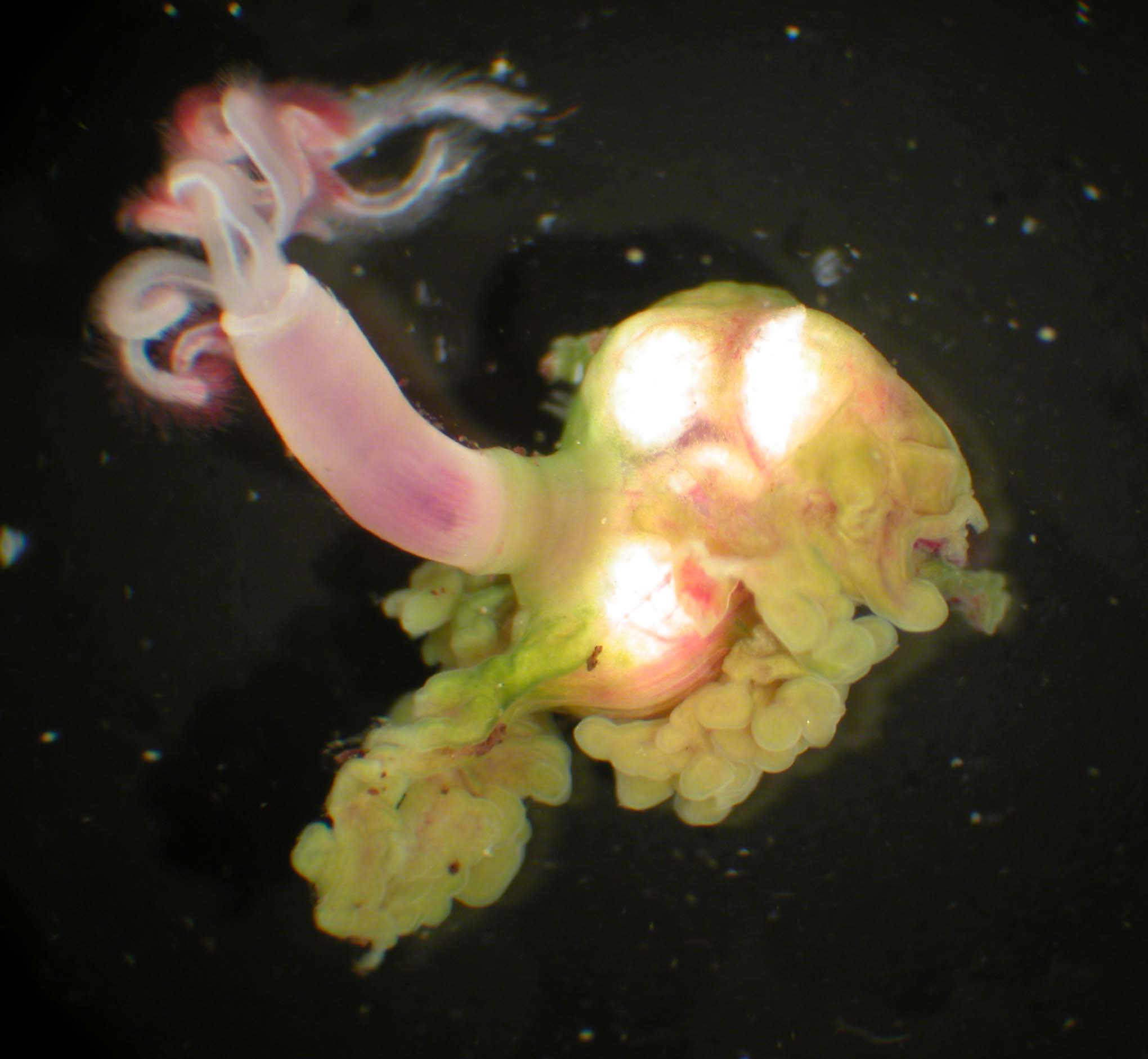

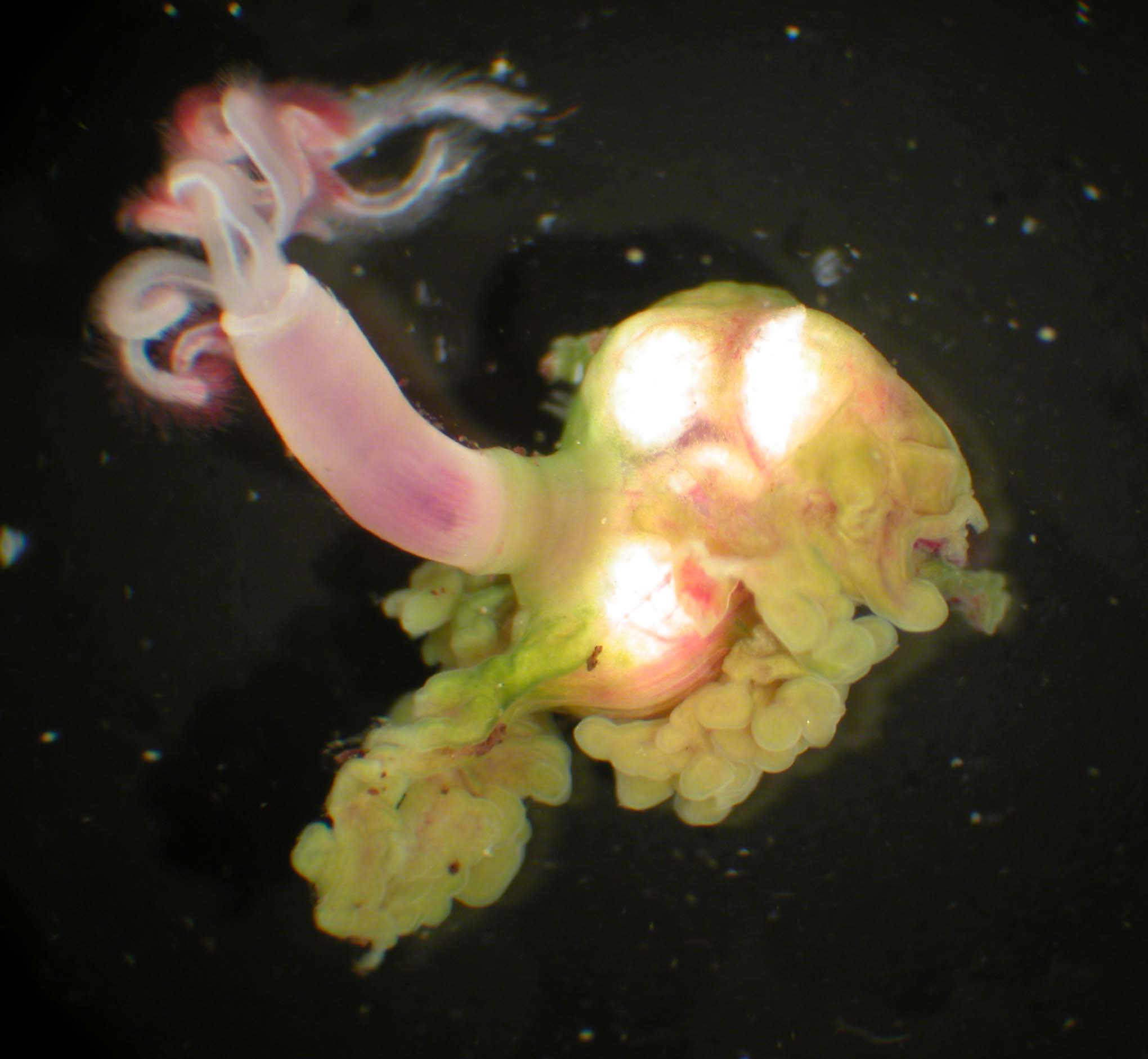

On whale bones, only the pinkish trunk of this cross-section of a female Osedax

tubeworm is visible. The white blobs are ovaries where more than 100 dwarf male

tubeworms can live inside the female. Symbiotic bacteria give the tubeworm's

roots their greenish color. Image copyright of Greg Rouse, 2003.

In this week's Science, Greg Rouse, a marine biologist

at the University of Adelaide in Australia, and others created a new genus,

Osedax, which translates as "bone devouring," to classify

the new organisms. Upon discovery, the researchers noticed the bone-eating worms

"shared some characteristics with the tubeworms at deep-sea vents,"

says Bob Vrijenhoek, a senior scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research

Institute and co-author of the paper. "But beyond that, we really didn't

know how they were related." Subsequent DNA testing revealed the two worms

are distant cousins. "It was probably in excess of 100 million years ago

the two groups spilt apart," Vrijenhoek says.

In 1977, scientists first discovered that entire ecosystems exist at the ocean

bottom along deep-sea vents and hydrocarbon seeps. Prior to that discovery,

scientists thought life could not exist without sunlight. Symbiotic bacteria

that live within the tubeworms process inorganic materials like sulfides or

methane and provide nutrients to the worms and surrounding communities. The

newly discovered tubeworms contain a type of bacteria that break down fats (a

type of hydrocarbon) inside of bones. "They are like termites, with symbiotic

bacteria in their guts, but they eat bone instead of wood," Vrijenhoek

says.

Apart from the use of symbiotic bacteria

and the absence of a mouth or gut, the two tubeworms are not very similar. "They

are relatively closely related but morphologically very distinct," Rouse

says. The tubeworms found at deep-sea vents can grow up to 10 feet in height,

but Osedax are only a few inches tall. Another major difference between

the tubeworms is the presence of roots. Many of the larger tubeworms have a

single root to help anchor them to the seafloor, however, Osedax has

roots "a lot like a tree," says Ken Halanych, a marine biologist at

Auburn University, who is not associated with the research. The root penetrates

the bone and "branches out and grows several different roots," he

says. The bone-digesting bacteria reside in these roots.

Apart from the use of symbiotic bacteria

and the absence of a mouth or gut, the two tubeworms are not very similar. "They

are relatively closely related but morphologically very distinct," Rouse

says. The tubeworms found at deep-sea vents can grow up to 10 feet in height,

but Osedax are only a few inches tall. Another major difference between

the tubeworms is the presence of roots. Many of the larger tubeworms have a

single root to help anchor them to the seafloor, however, Osedax has

roots "a lot like a tree," says Ken Halanych, a marine biologist at

Auburn University, who is not associated with the research. The root penetrates

the bone and "branches out and grows several different roots," he

says. The bone-digesting bacteria reside in these roots.

The Tiburon, operated by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute,

grabs the rib of a grey whale from the ocean floor. The red filaments on the

bone are the newly discovered tubeworm. Image copyright of MBARI,

2003.

Also, unlike tubeworms at deep-sea vents, Osedax is sexually dimorphic.

"In other tubeworms, males and females look similar; in these worms, the

males are microscopic," Halanych says. The so-called dwarf males, sometimes

numbering over 100, live inside the female tubeworms, next to their oviducts.

"This is a classic textbook example of bizarre marine invertebrate anatomy,"

says Cindy Van Dover, a marine biologist at the College of William and Mary

in Williamsburg, Va., and the first female pilot for the Alvin research

submarine.

The researchers who discovered the new tubeworms

used an unmanned, remotely operated vehicle, Tiburon. The scientists

watched TV screens on the boat while Tiburon scuttled along the seafloor

more than 9,000 feet below. They were studying clams that day and found the

whale bones and new tubeworms by coincidence. When the whale carcass came into

view, it looked "like a thick red carpet covering the bones," Vrijenhoek

says.

The researchers who discovered the new tubeworms

used an unmanned, remotely operated vehicle, Tiburon. The scientists

watched TV screens on the boat while Tiburon scuttled along the seafloor

more than 9,000 feet below. They were studying clams that day and found the

whale bones and new tubeworms by coincidence. When the whale carcass came into

view, it looked "like a thick red carpet covering the bones," Vrijenhoek

says.

Bacteria in the roots of Osedax

produce nutrients by processing the fats and lipids in the bones of whales.

Image copyright of MBARI, 2003.

The accidental discovery of the new organisms in the deep ocean underscores

the possibility for breakthroughs in understanding the deep ocean. "It

is very clear we still don't know a lot about the oceans," Halanych says.

"And this [Monterey Bay] is one of the best studied areas of the ocean

we have."

Jay Chapman

Geotimes Intern

Links:

"Worms

discovered living on whale bones," Associated Press story on CNN.com

The

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Science - "Osedax: Bone-Eating Marine Worms with Dwarf Males"

Back to top

Untitled Document

In Monterey Bay, off the coast

of California, researchers have discovered a group of extraordinary marine worms

that feed on the bones of dead whales. Even Jules Verne would have difficulty

imagining up these creatures whose closest relative may be the tubeworms found

at deep-sea vents.

In Monterey Bay, off the coast

of California, researchers have discovered a group of extraordinary marine worms

that feed on the bones of dead whales. Even Jules Verne would have difficulty

imagining up these creatures whose closest relative may be the tubeworms found

at deep-sea vents.

Apart from the use of symbiotic bacteria

and the absence of a mouth or gut, the two tubeworms are not very similar. "They

are relatively closely related but morphologically very distinct," Rouse

says. The tubeworms found at deep-sea vents can grow up to 10 feet in height,

but Osedax are only a few inches tall. Another major difference between

the tubeworms is the presence of roots. Many of the larger tubeworms have a

single root to help anchor them to the seafloor, however, Osedax has

roots "a lot like a tree," says Ken Halanych, a marine biologist at

Auburn University, who is not associated with the research. The root penetrates

the bone and "branches out and grows several different roots," he

says. The bone-digesting bacteria reside in these roots.

Apart from the use of symbiotic bacteria

and the absence of a mouth or gut, the two tubeworms are not very similar. "They

are relatively closely related but morphologically very distinct," Rouse

says. The tubeworms found at deep-sea vents can grow up to 10 feet in height,

but Osedax are only a few inches tall. Another major difference between

the tubeworms is the presence of roots. Many of the larger tubeworms have a

single root to help anchor them to the seafloor, however, Osedax has

roots "a lot like a tree," says Ken Halanych, a marine biologist at

Auburn University, who is not associated with the research. The root penetrates

the bone and "branches out and grows several different roots," he

says. The bone-digesting bacteria reside in these roots. The researchers who discovered the new tubeworms

used an unmanned, remotely operated vehicle, Tiburon. The scientists

watched TV screens on the boat while Tiburon scuttled along the seafloor

more than 9,000 feet below. They were studying clams that day and found the

whale bones and new tubeworms by coincidence. When the whale carcass came into

view, it looked "like a thick red carpet covering the bones," Vrijenhoek

says.

The researchers who discovered the new tubeworms

used an unmanned, remotely operated vehicle, Tiburon. The scientists

watched TV screens on the boat while Tiburon scuttled along the seafloor

more than 9,000 feet below. They were studying clams that day and found the

whale bones and new tubeworms by coincidence. When the whale carcass came into

view, it looked "like a thick red carpet covering the bones," Vrijenhoek

says.