Geotimes

Feature

Bringing Sustainability

to the People of Nunavut

Ross L. Sherlock, David J. Scott and Gordon MacKay

Nunavut is Canada’s newest territory, established on April 1, 1999. Encompassing

about 20 percent of Canada’s landmass and accounting for nearly 70 percent

of Canada’s coastline, Nunavut is roughly four and a half times the size

of Texas. The territory has 26 communities, with populations ranging from 130

people in Grise Fiord on Ellesmere Island to more than 5,000 people in Iqaluit

on Baffin Island, for a total population of about 28,000, 85 percent of whom

are Inuit.

Nunavut is Canada’s frontier, as isolated and remote as any place in the

world. No highways link the communities of Nunavut, and access to the territory

is only by air or sea. Located on tidal flats, all communities are icebound

six to 10 months of the year. The climatic conditions are harsh, with almost

all of the territory above the tree line and more than half the communities

above the Arctic Circle. Given the physical realities of Nunavut, the economy

has only limited directions in which to expand; the only practical means is

through responsible development of its natural resources.

Nunavut’s

geology is diverse, representing more than 3 billion years of Earth’s history

and encompassing many environments that are favorable for large ore bodies.

Nunavut hosts several of the largest undeveloped lode-gold deposits in Canada

— Meliadine, Meadowbank, Goose Lake-George Lake and Hope Bay — as

well as large undeveloped zinc resources at Izok Lake and copper resources at

High Lake. Recently a number of companies have been aggressively exploring for

diamonds in different regions of Nunavut, and initial results are quite promising.

In Nunavut, the potential to discover world-class mineral deposits is high.

Nunavut’s

geology is diverse, representing more than 3 billion years of Earth’s history

and encompassing many environments that are favorable for large ore bodies.

Nunavut hosts several of the largest undeveloped lode-gold deposits in Canada

— Meliadine, Meadowbank, Goose Lake-George Lake and Hope Bay — as

well as large undeveloped zinc resources at Izok Lake and copper resources at

High Lake. Recently a number of companies have been aggressively exploring for

diamonds in different regions of Nunavut, and initial results are quite promising.

In Nunavut, the potential to discover world-class mineral deposits is high.

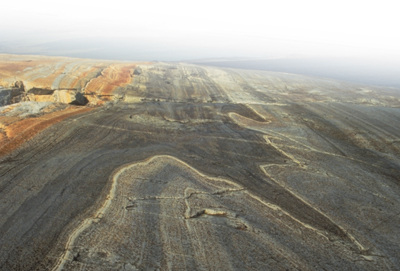

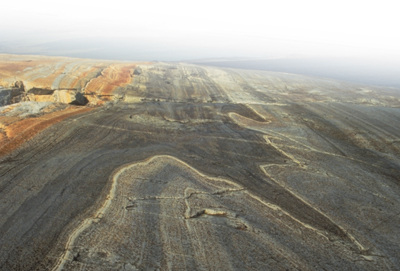

These folded metamorphic rocks are typical

of the ancient Canadian Shield bedrock that underlies Nunavut and is the source

of much of its mineral wealth. Photo courtesy of Governments of the Northwest

Territories and Nunavut.

The Government of Nunavut embraces the United Nations’ Brundtland definition

of sustainable development, which states that development must be undertaken

in ways that “meet the needs of the present, without compromising the ability

of future generations to meet their own needs” (see story,

this issue). This approach invariably involves maximizing the economic and

social benefits to local people through training and support, so that mine closures

leave the local communities in a sustainable state without environmental liabilities.

In Nunavut, responsible development of natural resources is viewed as a mechanism

to develop human capital, thereby creating a sustainable social and economic

climate that can expand beyond a reliance on resource extraction.

Exploration and future mining projects are part of a balance, with a healthy

diversified economy, environmental integrity and economic opportunities for

today that do not compromise opportunities for future prosperity. Individual

projects must use industry’s best practices and follow an underlying moral

imperative to develop mineral resources in a responsible manner. Each project,

however, is just part of a larger vehicle to ensure the economic and social

viability of the territory through the transfer of benefits to Nunavut residents

by development of its resources.

Meet the community

Key to understanding the concept of sustainable development in Nunavut is an

appreciation of the physical and socioeconomic realities of the territory. The

Inuit of Nunavut are in transition from a traditional to modern lifestyle. Many

of the older residents of Nunavut were born on the land and moved into modern

houses as children. Many Nunavummiut (residents of Nunavut of any ethnic background)

still spend a large portion of the year in Nunavut, hunting, fishing and gathering.

As a result, young Nunavummiut balance between the traditional lifestyle of

their elders and the modern lifestyle that they are exposed to via television

and the Internet.

Nunavut

has a very young and rapidly growing population; about 60 percent is under the

age of 25, and 41 percent under the age of 16. More than half the adult population

has not completed high school, and only a small percentage of the population

has a post-secondary education. Income levels in Nunavut are low, which, compounded

with the very high cost of living, result in more than half of Nunavummiut needing

some form of income support during any given year. Unfortunately, these socioeconomic

conditions have resulted in serious health problems, such as high incidences

of infant mortality, tuberculosis, diabetes, sexually transmitted diseases and

lung cancer.

Nunavut

has a very young and rapidly growing population; about 60 percent is under the

age of 25, and 41 percent under the age of 16. More than half the adult population

has not completed high school, and only a small percentage of the population

has a post-secondary education. Income levels in Nunavut are low, which, compounded

with the very high cost of living, result in more than half of Nunavummiut needing

some form of income support during any given year. Unfortunately, these socioeconomic

conditions have resulted in serious health problems, such as high incidences

of infant mortality, tuberculosis, diabetes, sexually transmitted diseases and

lung cancer.

Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory, has a very young population, with more

than half under the age of 25 and 40 percent under the age of 16. Photo courtesy

of Governments of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

Nunavut’s economy is a unique mix of traditional activities (hunting, fishing

and carving) as well as wage-based employment. The traditional activities are

very important in terms of providing food, modest financial gains, and preserving

the social and cultural infrastructure. However, the realities of the 21st century

require Nunavummiut to increase their participation in the wage economy if they

are to rise above the poverty line.

The wage-based economy in Nunavut is dominated by the public service industry,

representing almost 40 percent of Nunavut’s gross domestic product (GDP),

followed by mining and resource development (about 18 percent of GDP). The three

operating mines in Nunavut have recently closed due to depleted resources, which

will increase the economy’s reliance on government and government services.

In a recent study, the Conference Board of Canada concluded that Nunavut’s

reliance on government employment is not sustainable. The coming years will

see a large influx of Nunavummiut seeking employment; the economy must diversify

if the territory is to achieve sustainability.

Mineral rights

In 1993, the Inuit of Nunavut signed the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (NLCA).

Self-determination over resource development forms key sections in the agreement.

The NLCA gave the Inuit ownership of 356,000 square kilometers of land (about

16 percent of Nunavut) and combined surface and mineral rights to about 35,000

square kilometers (about 2 percent of Nunavut) of the most promising ground.

The mineral rights are held and administered by Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated

(NTI), the nonprofit corporation established primarily to oversee implementation

of the NLCA on behalf of the Inuit. Where the Inuit own the mineral rights,

NTI issues licenses to explore and mine through its own mineral-tenure system.

Although NTI holds mineral rights to only 2 percent of Nunavut, much of the

territory’s mineral wealth belongs to the Inuit of Nunavut.

Ownership of mineral resources is critical to the future economic prosperity

of Nunavut. The people of the territory, through NTI, regulate mining and exploration

and collect royalties on future operations. These royalties can be very significant.

A modern diamond mine, such as Ekati or Diavik in the Northwest Territories

of Canada, could provide royalties in excess of Can$600 million over a mine’s

25-year life. Similarly, modern gold or base metal mines could provide Can$10

million to Can$100 million in royalties over a 10- to 20-year mine life. NTI

can use these royalties to reinvest in the communities and directly improve

the quality of life of the Nunavummiut.

In addition to royalties, the NLCA requires that project proponents establish

impact-benefit agreements with the Inuit. These agreements typically create

direct employment and training opportunities, building capacity in Nunavut’s

communities and ensuring responsible development through community consultation

and shared-monitoring programs. A key requirement of these agreements is improvement

of basic education levels. Then, Nunavummiut will be able to participate in

these economic opportunities and consequently help retain the benefits of mining

in Nunavut.

Even prior to the commencement of mining operations, exploration projects offer

economic benefits. These projects contribute approximately 10 percent of their

total expenditures to the local communities, mainly through direct employment

and provision of goods and services. Although a relatively small proportion,

exploration programs in Nunavut are commonly in excess of Can$1 million per

year, which can have a very significant impact on a small community that consists

of several hundred people. Presently, the capacity of most communities is limited,

such that one or two exploration projects will fully engage the service capacity

of a community. This capacity gap is not unique to the exploration industry;

it is prevalent throughout the developing economy. As Nunavut’s economy

matures, and more impact-benefit agreements are completed, the capacity to service

all forms of industry will improve. Local communities can then capture more

of the benefits of exploration and other economic sectors.

Need for geoscience

A well-recognized relationship exists between the provision of public geoscience,

increased exploration activity, and discovery and development of new mineral

deposits. As established mines become depleted, exploration companies will increasingly

explore in more remote areas; but they need geologic information in order to

select areas and reduce their exploration risk. Public geoscience knowledge

(bedrock and surficial geological framework) is reasonably complete in many

mature jurisdictions of Canada and elsewhere; in these areas, the private sector

can identify energy and mineral resources. Nunavut, however, as a frontier jurisdiction,

lags far behind the rest of Canada in terms of providing a comprehensive geoscience

database at a regional level. Large areas of the territory have never been mapped

at a scale that is useful for mineral exploration or for making informed land-use

planning decisions. Thus, there is an enormous opportunity for new mapping to

stimulate further exploration.

Nunavut is competing worldwide for exploration dollars; companies can go anywhere

in the world to explore and develop mineral deposits. To successfully compete,

Nunavut needs to demonstrate its mineral potential through developing and maintaining

a high-quality geoscience knowledge base that is available and readily accessible

to the public. Ultimately, this knowledge will enable the discovery and development

of mineral resources that will benefit the Nunavummiut, and allow the territory

to develop a sustainable social and economic climate that can expand beyond

a reliance on resource development. Although the potential to discover new economic

mineral deposits is high, government-funded earth science must provide the geologic

framework to facilitate these discoveries.

Sherlock is a research scientist

with the Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office (C-NGO) in Iqaluit, where he conducts

research projects on mineral deposits in Nunavut.

Scott is the program manager of the Geological Survey of Canada’s Northern

Resources Develop-ment Program, overseeing geoscience projects across Canada aimed

at supporting sustainable development in Canada’s north. He was the founding

chief geologist of the C-NGO in Iqaluit, a partnership formed to build geoscience

capacity in Nunavut.

MacKay is the director of Environment and Integrated Resource Management with

the Government of Nunavut’s Department of Sustainable Development. As a professional

geologist with close to 20 years experience in government and the mining industry,

MacKay is working to support the development of a strong Nunavut economy.

Link:

"Sustainable Development and the Use of

Nonrenewable Resources," Geotimes, December 2003

Back to top

Nunavut’s

geology is diverse, representing more than 3 billion years of Earth’s history

and encompassing many environments that are favorable for large ore bodies.

Nunavut hosts several of the largest undeveloped lode-gold deposits in Canada

— Meliadine, Meadowbank, Goose Lake-George Lake and Hope Bay — as

well as large undeveloped zinc resources at Izok Lake and copper resources at

High Lake. Recently a number of companies have been aggressively exploring for

diamonds in different regions of Nunavut, and initial results are quite promising.

In Nunavut, the potential to discover world-class mineral deposits is high.

Nunavut’s

geology is diverse, representing more than 3 billion years of Earth’s history

and encompassing many environments that are favorable for large ore bodies.

Nunavut hosts several of the largest undeveloped lode-gold deposits in Canada

— Meliadine, Meadowbank, Goose Lake-George Lake and Hope Bay — as

well as large undeveloped zinc resources at Izok Lake and copper resources at

High Lake. Recently a number of companies have been aggressively exploring for

diamonds in different regions of Nunavut, and initial results are quite promising.

In Nunavut, the potential to discover world-class mineral deposits is high.

Nunavut

has a very young and rapidly growing population; about 60 percent is under the

age of 25, and 41 percent under the age of 16. More than half the adult population

has not completed high school, and only a small percentage of the population

has a post-secondary education. Income levels in Nunavut are low, which, compounded

with the very high cost of living, result in more than half of Nunavummiut needing

some form of income support during any given year. Unfortunately, these socioeconomic

conditions have resulted in serious health problems, such as high incidences

of infant mortality, tuberculosis, diabetes, sexually transmitted diseases and

lung cancer.

Nunavut

has a very young and rapidly growing population; about 60 percent is under the

age of 25, and 41 percent under the age of 16. More than half the adult population

has not completed high school, and only a small percentage of the population

has a post-secondary education. Income levels in Nunavut are low, which, compounded

with the very high cost of living, result in more than half of Nunavummiut needing

some form of income support during any given year. Unfortunately, these socioeconomic

conditions have resulted in serious health problems, such as high incidences

of infant mortality, tuberculosis, diabetes, sexually transmitted diseases and

lung cancer.