This

week, scientists further confirmed the presence of water on Mars, almost a year

after the Mars Exploration Rovers landed on the fourth rocky planet from the

sun. Spirit, which is now in the Columbia Hills and 336 martian days into its

travels on Mars, finally found evidence of water, several months after its twin

Opportunity did. And Opportunity continues to see further signs of water on

Mars, from the ground to the sky.

This

week, scientists further confirmed the presence of water on Mars, almost a year

after the Mars Exploration Rovers landed on the fourth rocky planet from the

sun. Spirit, which is now in the Columbia Hills and 336 martian days into its

travels on Mars, finally found evidence of water, several months after its twin

Opportunity did. And Opportunity continues to see further signs of water on

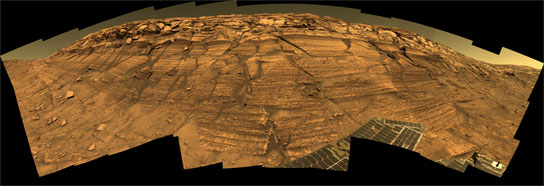

Mars, from the ground to the sky.This panorama image of Burns Cliff on Mars was taken by the rover Opportunity, while it was perched below the tens of meters of rhythmic layers in the cliff wall. The composite image makes the gently curving cliff face appear to bulge towards the rover. Courtesy of NASA/JPL.

After landing in Gusev Crater last January (halfway around the planet from twin rover Opportunity's landing site later that month), Spirit exited its terrain of volcanic deposits and bare soils around its 150th day on Mars. Seven martian days later, it entered the hills that it is now traversing, where it has seen sedimentary rocks with fine, almost horizontal layering that contains sometimes-cemented granules that vary in size and angularity.

"We think these are deposits from a fluid," said Raymond Arvidson of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., at a press conference on Monday at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. The team is now debating whether the granules deposited are from volcanic ash or impact deposits from a later event, with chemical and mineralogical signatures that are very different from the volcanic deposits that Spirit first saw. Whether or not "it's an impact ash transported by fluid, we just can't tell yet," Arvidson said.

In its transition to a different landscape, Spirit also has stumbled across a surprising mineral that further confirms the presence of water in some form: goethite, a mineral that is common on Earth. "It doesn't necessarily need to have liquid water" to form, said Goestar Klingelhoefer of Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany, who is the lead scientist for the Moessbauer Spectrometers onboard both rovers. Klinghoefer said that the goethite [pronounced GUR-tite] could have formed in the presence of water vapor or maybe ice. "That's one of the things we need to look more closely at in the data."

Until last Sunday (Earth time), Spirit's twin Opportunity continued to examine the Endurance Crater, and in particular Burns Cliff, a thick sequence of sulfate-rich rocks. Opportunity managed to climb halfway up the cliff, and is mapping the lithologic layers by comparing what it has found with exposures on other faces in the crater. The result should be a 3-D map of at least one layer.

And, said principal investigator Steve Squyres of Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., Opportunity found a distinct unconformity between what looks like aeolian dunes topped by finer layers probably deposited in liquid water. "Don't think deep ocean; think 'a playa,'" he said, with intermittently wet and dry conditions. Squyres also noted that Opportunity observed a new mineral in the past few days, something that the team has not yet had time to identify, but which he will show pictures of in his talk later this week.*