Geotimes

Untitled Document

Web Extra

Friday, December 17, 2004

A Saturnian one-two punch:

Flybys of Titan and Dione

On Monday, the Cassini-Huygens

spacecraft flew by Titan only 1,200 kilometers above the moon's surface. It

was the second such flyby of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, since the spacecraft

began orbiting Saturn on June 30. Then on Tuesday, Cassini-Huygens flew by Dione,

another of Saturn's moons, at 82,000 kilometers, providing the closest glimpse

ever of its enticing surface.

On Monday, the Cassini-Huygens

spacecraft flew by Titan only 1,200 kilometers above the moon's surface. It

was the second such flyby of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, since the spacecraft

began orbiting Saturn on June 30. Then on Tuesday, Cassini-Huygens flew by Dione,

another of Saturn's moons, at 82,000 kilometers, providing the closest glimpse

ever of its enticing surface.

"We're very excited," said Dennis Matson, project scientist on the

Cassini-Huygens mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) at Caltech

in Pasadena, Calif., during a presentation at the fall meeting of the American

Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco on Tuesday. Both of these flybys have

provided Earth-bound scientists with new data, images and surprises, as they

eagerly await the Huygens descent through Titan's atmosphere beginning on Christmas

Eve.

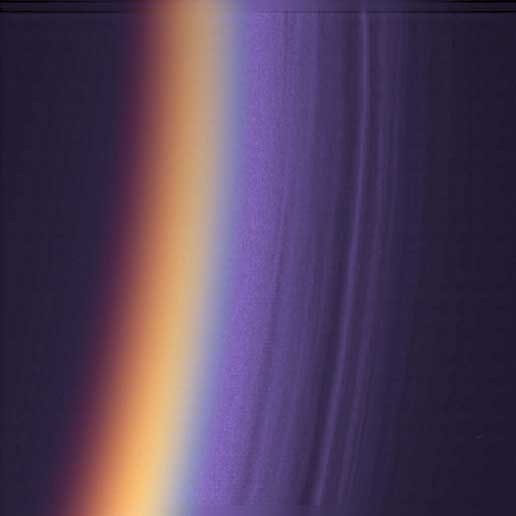

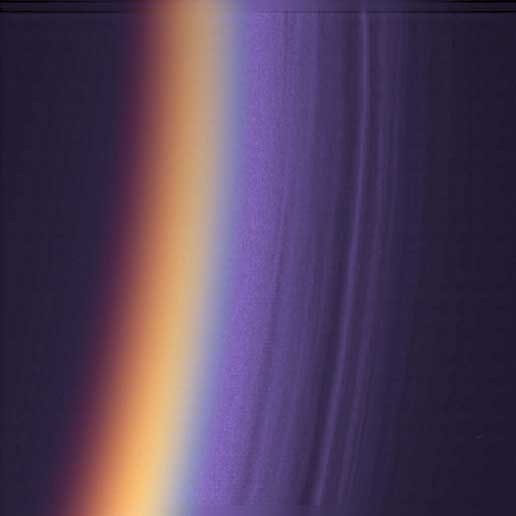

Layers of haze compose Titan's upper atmosphere,

photographed in ultraviolet by Cassini and modified to appear in true color.

Images of Titan from Monday's flyby and of Dione are posted on the Jet

Propulsion Lab (JPL) Web site. Courtesy

NASA/JPL.

Scientists say that Titan, which is larger than Mercury and Pluto, is one of

the most likely places in our solar system to find extraterrestrial life, as

it is the only known body to have an atmosphere. And Monday's flyby has confirmed

what atmospheric models had predicted, and revealed some new surprises about

the moon's murky orange skies and topographic features since the spacecraft's

last flyby on Oct. 26, said Linda Spilker of JPL, deputy Cassini-Huygens project

scientist, at a press conference on Thursday.

One of those surprises, said Kevin Baines, a Cassini Science Team member, was

that the clouds that had been observed by the previous flyby had moved, providing

the scientists with "something to study." The cloud movement is also

the first evidence of weather on Titan, Baines said. The clouds moved much more

slowly than previous images had revealed and looked to be at lower altitudes

as well. Cassini's flyby also observed multiple atmospheric layers (perhaps

as many as 12 or more), and at least one very thick one that looks as though

it is composed of hydrocarbons, Baines said.

Through the atmospheric haze, Cassini was also able to image bright circular

or spiral-shaped features, said Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team leader at

the Space Science Institute in Colorado. Although the scientists are excited,

they have no idea what the features are, or if they are depressions or uplifts,

Porco said at Thursday's press conference. The same was true after the October

flyby revealed what appear to be lava domes and flows.

Until they have a chance to look at the various features with synthetic aperture

radar and radar altimetry data, Porco said, the scientists won't know the 3-D

landscape — they'll just have to keep guessing about "what's high

and what's low." That opportunity may come in February or March, when scientists

will be able to use

to get a better idea of the topography.

The topography of another

moon, Dione, is being revealed much more quickly than on Titan, especially following

this week's exciting flyby. When Voyager flew by Dione in 1980, it caught glimpses

of a "wispy terrain," which is considered the "most distinctive

feature on this satellite," Porco said. Since then, scientists believed

that the wisps were probably thick ice depositions. However, from the latest

flyby, scientists now say that thick ice deposits were not the primary feature.

Instead, the satellite is pockmarked with impact craters, and crisscrossed with

fractures and cliff faces that appear to be very deep.

The topography of another

moon, Dione, is being revealed much more quickly than on Titan, especially following

this week's exciting flyby. When Voyager flew by Dione in 1980, it caught glimpses

of a "wispy terrain," which is considered the "most distinctive

feature on this satellite," Porco said. Since then, scientists believed

that the wisps were probably thick ice depositions. However, from the latest

flyby, scientists now say that thick ice deposits were not the primary feature.

Instead, the satellite is pockmarked with impact craters, and crisscrossed with

fractures and cliff faces that appear to be very deep.

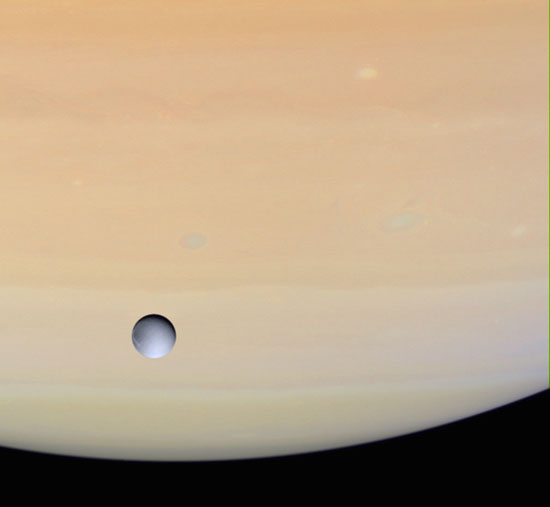

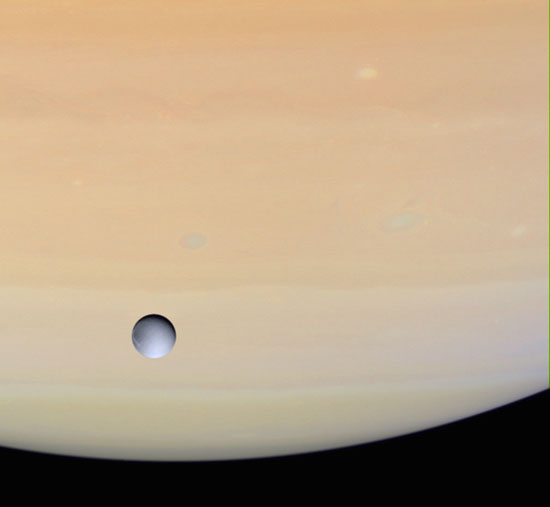

Saturn looms behind its moon Dione, photographed on Dec. 14 as Cassini approached

for a closer view. Courtesy NASA/JPL.

Those fractures and cliff faces look like wisps from far away, but the close

view provided by Cassini reveals not a thick ice deposit to be found. This is

very surprising, Porco said. Some of the team members, Porco said, suggest that

this type of complex system of fractures is what they would expect if Dione

had started out as slush and then solidified. "This has been a delightful

and surprising encounter," she said, with many more years of analysis to

come.

For the next four years of the Cassini mission, the spacecraft will fly by Titan

every month or so. Of more immediate interest, however, is the Huygens probe's

descent into Titan's atmosphere. On Dec. 24, Huygens will detach from its galactic

taxi, Cassini, and will enter Titan's atmosphere. For 21 days, the probe will

float through the atmosphere, sending images and data signals to Cassini, which

will relay the data back to Earth. Then on Jan. 14, Huygens will begin its descent

onto Titan. Three parachutes will deploy to slow the probe's landing and to

provide a stable platform for scientific measurements — very possibly the

last contact scientists will have with the probe.

The entire descent will last about two and a half hours, Matson said, "and

there's no way to guarantee where we'll land or how. We could land in water,

snow, on rock." The scientists have aimed the landing at a dark area on

the moon that they hope represents a liquid surface (perhaps water) near the

equator, based on images already taken by Cassini. Wherever it lands, he said,

there's little guarantee that Huygens will land right-side-up or that it will

survive the landing.

Regardless of whether or not the probe survives, Matson said, NASA and its partners

are hopeful that as it lands, the probe will give them even more detailed information

than it has already sent back. "The best is yet to come," he said.

Other interesting results are coming from Saturn (see sidebar)

and from the planet's other moons, including Phoebe, which Cassini zoomed by

last summer (see Geotimes Web Extra).

The close view of that satellite revealed temperatures, carbon dioxide levels,

iron content and ice content, as well as craters, Matson said.

Cassini is the fourth NASA spacecraft to explore Saturn. Pioneer 11 passed by

in 1979, Voyager in 1980 and Voyager 2 in 1981. Cassini is the first mission,

however, to orbit the planet. The Cassini-Huygens mission is a collaborative

project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The

Huygens probe was named after Christian Huygens, a Dutch astronomer who discovered

Titan in 1655.

Megan Sever

Saturn's

surprises

As Cassini continues to get new views of some of Saturn's more than 30 moons,

researchers have plenty of other data to analyze about the planet's composition,

its huge and complex magnetosphere, and its famous rings.

Since the spacecraft reached Saturn's orbit in July, scientists have learned

more about the composition and grain size of the planet's rings, which extend

hundreds of thousands of miles from the planet and are composed of billions

of particles of ice and rock, ranging from the size of sand grains to cars

and houses. Right now, they only understand about 5 percent of the rings,

said Jeff Cuzzi of the NASA Ames Research Center in California, but that

is changing quickly.

Cassini has imaged at least three new ringlets within the D ring that were

not there when Voyager flew by — indicating that the rings are very

dynamic and variable. Cassini has also revealed a "buried treasure"

in the mass-heavy B ring, Cuzzi said in a presentation at the annual fall

meeting of the American Geophysical Union on Tuesday: Some reddish organic

material is mixed in; most of the rings are composed of 90 percent water.

Also, he said, certain regions of the rings have proven to be very "polluted"

by meteoroid bombardment.

The rings, along with Saturn's icy satellites, may also be contributing

to the vast amount of water in Saturn's magnetosphere, which is nearly a

factor of 10 higher than the scientists had thought, said Tamas Gombosi

at the University of Michigan, who is a member of the Magnetosphere and

Plasma Science working group on the mission. Cassini imaged the planet's

magnetosphere — a magnetic envelope of charged particles that surrounds

some planets, including Earth — for the first time. The large mass

of water could have important consequences for the magnetosphere, which,

Gombosi said, is particularly interesting because it combines a number of

properties usually only seen in one source. The scientists are now trying

to figure out what breaks the water out of the rings and drags it into the

magnetosphere.

In studying Saturn, there's never a dull moment, as Dennis Matson, project

scientist on the Cassini-Huygens mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

(JPL) at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., said: "Every time we think we

see something, it turns out not to be what we thought it was — we're

stumbling through and faced with the challenge of interpretation."

MS

|

Links:

NASA's

Cassini mission home page

NASA

JPL Cassini-Huygens project

"Sliding into

Saturn," Geotimes Web Extra, July 2, 2004

Back to top

Untitled Document

On Monday, the Cassini-Huygens

spacecraft flew by Titan only 1,200 kilometers above the moon's surface. It

was the second such flyby of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, since the spacecraft

began orbiting Saturn on June 30. Then on Tuesday, Cassini-Huygens flew by Dione,

another of Saturn's moons, at 82,000 kilometers, providing the closest glimpse

ever of its enticing surface.

On Monday, the Cassini-Huygens

spacecraft flew by Titan only 1,200 kilometers above the moon's surface. It

was the second such flyby of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, since the spacecraft

began orbiting Saturn on June 30. Then on Tuesday, Cassini-Huygens flew by Dione,

another of Saturn's moons, at 82,000 kilometers, providing the closest glimpse

ever of its enticing surface.

The topography of another

moon, Dione, is being revealed much more quickly than on Titan, especially following

this week's exciting flyby. When Voyager flew by Dione in 1980, it caught glimpses

of a "wispy terrain," which is considered the "most distinctive

feature on this satellite," Porco said. Since then, scientists believed

that the wisps were probably thick ice depositions. However, from the latest

flyby, scientists now say that thick ice deposits were not the primary feature.

Instead, the satellite is pockmarked with impact craters, and crisscrossed with

fractures and cliff faces that appear to be very deep.

The topography of another

moon, Dione, is being revealed much more quickly than on Titan, especially following

this week's exciting flyby. When Voyager flew by Dione in 1980, it caught glimpses

of a "wispy terrain," which is considered the "most distinctive

feature on this satellite," Porco said. Since then, scientists believed

that the wisps were probably thick ice depositions. However, from the latest

flyby, scientists now say that thick ice deposits were not the primary feature.

Instead, the satellite is pockmarked with impact craters, and crisscrossed with

fractures and cliff faces that appear to be very deep.