America’s national

parks are facing a financial crisis: Overall, the parks have a $600 million

shortfall, on top of a maintenance backlog estimated at $4.5 billion to $9.7

billion, according to the National Parks Conservation Association. In response,

the National Park Service (NPS) and Congress are devising new priorities, guidelines

and methods for fundraising, some of which have proven controversial.

America’s national

parks are facing a financial crisis: Overall, the parks have a $600 million

shortfall, on top of a maintenance backlog estimated at $4.5 billion to $9.7

billion, according to the National Parks Conservation Association. In response,

the National Park Service (NPS) and Congress are devising new priorities, guidelines

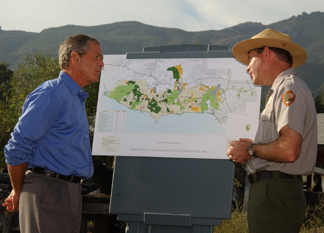

and methods for fundraising, some of which have proven controversial.President Bush met with National Park Service employees in California’s Santa Monica Mountains in August 2003, to address maintenance backlogs in the parks, which are estimated to be $4.5 billion to $9.7 billion. Image courtesy of DOI.

NPS, established in 1916 as a federally funded agency to preserve public lands, is responsible for 388 sites, from Rocky Mountain National Park to the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington, D.C. Traditionally, protection and conservation have been the focus of park system management, says Bill Wade, former superintendent at Shenandoah National Park and chair of the executive council of the Coalition of NPS Retirees. But priorities could change toward a heavier emphasis on recreational use, according to language in a newly revised management plan, he says, in review until mid-January.

Strategies are also shifting for funding the park service, which is underfunded annually by one-third, says Craig Obey, head of the National Parks Conservation Association, a nonprofit advocacy group set up in 1919 for the national parks and the park system. Although NPS has always relied on philanthropy, from land gifts to money from nonprofit foundations, such as the National Parks Foundation, as well as new and old “friends” groups affiliated with specific parks, the current NPS administration is putting a “strong increasing emphasis” on partnerships with nonprofit organizations and others, Wade says. “The shift has been dramatic in the last several years in increasing revenues from these organizations,” a reliance Wade and others find worrisome.

Now, an additional revenue source could be corporate gifts, in a policy announced by NPS Director Fran Mainella on Oct. 6 (the 60-day review period ends Dec. 5). While Wade and others say that allowing commercial interests in national parks could have unexpected pitfalls, Ken Olson, the president of Friends of Acadia National Park in Maine, says that “there is a place for corporate funding in national parks. It’s just a matter of how tastefully the contributions are carried out.”

In the meantime, friends groups are funding more and more of what may be considered national parks’ everyday activities. According to a business plan conducted several years ago, Acadia’s shortfalls amount to about 53 percent of its current congressionally mandated budget, whereas most parks are operating with around 30 percent shortfalls. Even though the Acadia Friends organization’s philosophy is to not fund daily government operations, the group’s money still supports employees who maintain more than 100 kilometers of carriage roads originally gifted to the park by the Rockefeller family.

“We’ve crossed the bright line,” says Debra Tuck, head of the Grand Canyon National Park Foundation, “between federal responsibility and private opportunity.” Established in 1995, Grand Canyon National Park Foundation has raised $14 million in mostly private donations, with only 5 percent from corporations — given to such projects as trail-building on both rims of the Grand Canyon, controlling invasive species in the canyon itself and protecting endangered wild condors. “If we didn’t fund the condor program, the program would not be funded,” Tuck says. With one wildlife biologist for the entire 4-million-square-kilometer park, she says the organization must help fund science there.

Olson says that if cuts from Congress continue, philanthropy groups will lose their private donors, particularly if donations “are offset by cuts at the park level,” in programs or infrastructure. Philanthropic donors typically withdraw funding from what they perceive to be poorly supported enterprises, he and other foundation heads say.

Congress has weighed in on its responsibility in several ways. Last April, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Rep. Mark Souder (R-Ind.) sponsored bills in each house to provide funds to address the maintenance backlog, among other issues, under the National Parks Centennial Act. Currently under consideration, those bills will not come to fruition for some time, observers say.

The most recent high-profile proposals for change in the national park system have come from Rep. Richard Pombo (R-Calif.). Among other declarations, Pombo listed 15 national historic sites and reserves to sell. Compromises in October took much of that language out of his bill.

Pombo also called for reopening national park lands to mining and resource industry bids, governed by the 1872 General Mining Law. Pombo would increase the controversial law’s low fees — $2.50 or $5 an acre — to $1,000 per application. Whether Congress will accept these measures remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, the budget for fiscal year 2006 cuts back on national park funding by about 1 percent. It is also millions of dollars less than what parks received five years ago.

With inflation, the real-dollar reductions leave park superintendents in a bind to decide what to fund, which normally ends up being mandated cost-of-living increases for employee salaries and other basic operating costs, rather than maintenance or programs deemed unnecessary.