More than 250

years after astronomers first discovered Saturn’s moon Hyperion, the odd

celestial body is still presenting surprises. A closer-than-ever view of the

moon revealed a heavily cratered surface, which looks remarkably like a sponge.

More than 250

years after astronomers first discovered Saturn’s moon Hyperion, the odd

celestial body is still presenting surprises. A closer-than-ever view of the

moon revealed a heavily cratered surface, which looks remarkably like a sponge.

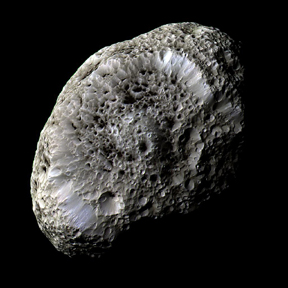

This false-color image of Saturn’s moon Hyperion, obtained during Cassini’s close flyby on Sept. 26, 2005, exposes the extensive craters that cover the surface. Color variations could represent differences in the composition of surface materials. Image courtesy of NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Images from the Voyager 2 mission in the early 1980s and ground-based observations previously hinted at Hyperion’s unique features, which included its unpredictable rotation and elongated shape. New images from the Sept. 26 flyby of the Cassini spacecraft are revealing numerous well-preserved craters also. The images depict the moon’s features in unprecedented detail, according to a Sept. 29 press release from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and scientists hope that close analysis will expose the cause of Hyperion’s uncommon appearance.

The odd look caught the interest of Peter Thomas, a senior research associate at the Cornell Center for Radiophysics and Space Research in New York, who studies surface processes that drive change on celestial bodies. “It certainly looks spongy compared to any other object,” Thomas says.

Hyperion’s resemblance to a sponge, however, is a false front. Close examination revealed that the look is “probably due to lots of craters shoulder to shoulder,” Thomas says. But the curious thing, he says, is that most other bodies do not retain such a large number of craters; fresh ejecta thrown out during new collisions are typically pulled back by gravity to fill in the crater. The craters on Hyperion “clearly don’t degrade like [on] other objects,” Thomas says. “The question is: why are they preserved so well?”

The answer may be the result of Hyperion’s close orbit to Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Thomas says that the suggestion made 20 years ago that Titan’s gravity might prevent Hyperion’s ejecta from falling back to fill the craters might be correct.

Also compounding the spongy appearance in the image are the wide color variations, which NASA says represent differences in surface materials. Centers of craters appear darker, and researchers are interested in determining the composition of this shallow material. Regions that look as if craters have washed away appear lighter, and could be the result of landslides, researchers say.

Additional study will allow scientists to turn up more answers. “We’ve got these images and we are just barely getting started figuring out the details,” Thomas says.