Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers

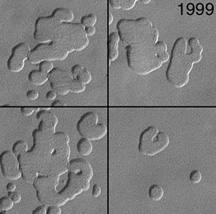

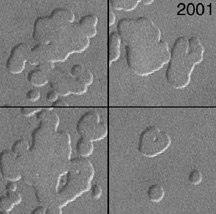

Compare each image on the left its their counterparts on the right. Small hills

vanished and pit walls expanded between 1999 and 2001.The south polar pits,

formed in frozen carbon dioxide,expand as the carbon dioxide sublimates away

a little more each martian year. Sunlight illuminates each scene from the upper

left. Courtesy of NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems.

Images taken by the spacecraft’s

camera system over a the course of a full martian year (687 Earth days) showed

that pits in the planet’s perennial southern polar ice cap are growing dramatically.

The only material that might have sublimated into gas so quickly was carbon

dioxide ice (dry ice), which was enlarging the pits by measurable amounts. The

images confirmed a decades-old suspicion among researchers that the planet’s

surface ice was made of solid carbon dioxide instead of frozen water. “This

is prima facie evidence of climate change,” says Michael Malin, of Malin Space

Science Systems in San Diego, who, along with colleagues Michael Caplinger and

Scott Davis, is principal investigator for the Global Surveyor’s camera system.

“The measurements have rather profound implications, and bring into question

a number of our views about the short-term stability of the martian climate.”

The pits are enlarging so quickly that the entire upper layer of the ice cap

is likely to be sublimated to gas within a martian decade or two. Because carbon

dioxide is a greenhouse gas, the pressure and temperature of the martian atmosphere

may change dramatically over periods as short as a few hundred years.

If enough carbon dioxide is present in Mars’ south polar ice cap, it could potentially

raise surface pressures enough to result in temperatures sufficiently warm for

surface water to exist. Malin and Kenneth Edgett published a paper in the June

30, 2000, issue of Science describing evidence of gullies on the martian

surface that may have been created by recent water flows.

Observations made with the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) were described

in a separate study in the same issue of Science. A paper by David Smith,

Maria Zuber and Gregory Neumann presented detailed measurements of the

planet’s topography and gravitational field suggesting significant changes in

the martian atmosphere within the space of a single martian year.

Because it is also tilted on its rotational axis, Mars has seasons like Earth.

As its surface gradually becomes darker during the martian autumn and winter,

carbon dioxide gas “freezes out” of the atmosphere. Dense dry-ice snow accumulates

at both poles, demarcated by a “frost line” that reaches the planet’s mid-latitudes

by winter. In spring and summer the process reverses.

Smith’s paper described how up to 2 meters of dry-ice snow accumulates in winter,

mostly at latitudes above 80 degrees. The authors also reported a tiny change

in the martian gravity field reflecting a global-scale mass redistribution.

So much carbon dioxide is exchanged between Mars’s atmosphere and surface —

as much as a third of the planet’s carbon dioxide over a full martian year —

that the planet, which like Earth is slightly flattened, actually becomes rounder

in winter.

“This is the first precise measurement of the global-scale cycling of the most

abundant atmospheric gas on Mars,” says Maria Zuber, deputy principal investigator

of MOLA and a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NASA’s

Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “Understanding the present carbon

dioxide cycle is an essential step toward understanding past climates.”

Malin adds, “Mars may help us decipher how natural climate systems, on Mars

and Earth, respond to rapid perturbations. The observations, if they do

in fact lead to climate changes on Mars, also suggest that natural climate change

may completely dominate human-induced climate change. Some people have suggested

‘terraforming’ Mars [altering its environment to make it more habitable], but

our observations suggest that Mars is already experiencing a larger change than

humans may ever be able to induce.”

As evidence accumulates of significant, ongoing climate change on Earth, severe

fluctuations in the martian climate strike closer to home. “There is quite a

bit of evidence that suggests that severe episodic or catastrophic phenomena

are much more common in nature than we have thought,” Malin says. “Certainly

my research both on Earth and Mars strongly points to such processes as being

most crucial in shaping the landscape.”

Julian Smith

Geotimes contributing writer

This story first appeared as a Web Extra

on Jan. 11, 2002.

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |