During the spring

of 1997, a team of oceanographers lowered a bright yellow, uniquely-tailored

sound source into calm seas off the coast of Vancouver Island, Canada. As the

source cruised just above the ocean floor, pulled by the ship above, it emitted

low frequency sound pulses that penetrated the icy sediments. A long streamer

trailing behind the source captured reflected sound waves and translated them

into a detailed image of the sediments beneath.

During the spring

of 1997, a team of oceanographers lowered a bright yellow, uniquely-tailored

sound source into calm seas off the coast of Vancouver Island, Canada. As the

source cruised just above the ocean floor, pulled by the ship above, it emitted

low frequency sound pulses that penetrated the icy sediments. A long streamer

trailing behind the source captured reflected sound waves and translated them

into a detailed image of the sediments beneath.The images from that trip, published in the Dec. 12 Nature, give the closest look yet at sediments bearing methane hydrates — gases trapped in ice-like structures. The images reveal features affecting the distribution and stability of hydrates invisible to conventional seismology, suggesting that perhaps all hydrates need to be viewed under a stronger lens before geoscientists can fully understand the nature of these vast reservoirs of gas.

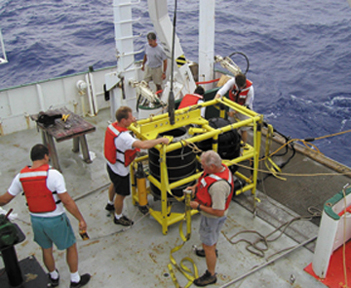

Oceanographers prepare to deploy the Deep-Towed Acoustic/Geophysics System, which has generated detailed seismic images suggesting that methane hydrate reservoirs might not be as stable as once thought. Photo by Warren Wood.

“The images add a fundamentally new perspective to gas hydrate systems,” says Ingo Pecher, a geologist with the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in New Zealand. “I really think the results will lead to some very exciting and profound changes in our view of gas hydrate reservoirs.”

Oceanographers have long known that the sediments in the Cascadia margin off the coast of Vancouver hold large amounts of methane hydrates. The area has become a natural laboratory for studying hydrates (Geotimes, December 2002).

Conventional seismic images, in which the sound source and receivers are trailed near the surface of the water, have indicated that the hydrates persist from just below the ocean floor down to about 300 meters within the sediments. The images also suggest that the base of hydrate stability, the depth at which the sediments become hot enough to melt the hydrates, is smooth and runs parallel to the ocean floor.

The new images, which are ten times more detailed than the conventional ones, refute the idea of a smooth base. In these images, the base appears convoluted, with peaks and valleys; the peaks bring the base almost to the surface of the ocean floor. The authors argue that the peaks result from fissures that allow warm fluids to migrate up into the surface sediments. The warmth of the fluids melts any hydrates that might form within or near the fissures, freeing the gas from its ice cages and creating what the authors term gas chimneys.

The importance of the chimneys lies in the fact that methane hydrates near the chimneys are on the brink of melting. Any slight increase in temperature (from warming ocean water) or drop in pressure (from lower sea level) can cause the ice cages to break down, releasing the gas. The presence of the chimneys therefore increases the overall fraction of the gas hydrate reservoir poised for release. “The chimneys could make the mechanism of methane release a bit more rapidly,” says lead author Warren Wood, an oceanographer with the Naval Research Laboratory at the Stennis Space Center in southern Mississippi, which funded the study.

“It is too early to speculate on how much of an impact the new results will have on assessing the quantities, distribution, and stability of gas hydrates since we don’t know how ubiquitous such gas chimneys are,” Pecher says. But, he adds, “We ‘conventional seismologists’ may need to adjust the designs of gas hydrate surveys to look for such gas chimneys.”

Greg Peterson