The

time period from 32 to 24 million years ago has largely been a black hole for

paleontologists studying East Africa's animals — they have had very little

information about life, or death, during those 8 million years. Newly discovered

large vertebrate fossils from Ethiopia, however, are providing evidence that

not only was there a thriving and diverse population, but also that it continued

long after.

The

time period from 32 to 24 million years ago has largely been a black hole for

paleontologists studying East Africa's animals — they have had very little

information about life, or death, during those 8 million years. Newly discovered

large vertebrate fossils from Ethiopia, however, are providing evidence that

not only was there a thriving and diverse population, but also that it continued

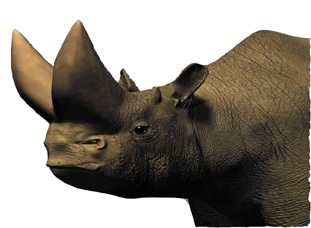

long after. A new species of Arsinoitherium recently found in Ethiopia is the largest (about 7 feet tall) and youngest (27 million years old) yet discovered. Image by Trent L. Shindler, National Science Foundation.

John Kappelman, a paleontologist at the University of Texas in Austin, led an international team of researchers into the high plateaus of Ethiopia to look for Tertiary fossil-bearing sediments. The team found more than 70 fossil localities with vertebrates, invertebrates and plants that were all contemporaneous and dated to this time period, as reported in the Dec. 4 Nature. "Kappelman et al. provide our first glimpse into the period," wrote Jean-Jacques Jaeger of the Institute of Evolution at Montpellier University in France in an accompanying commentary in the same issue.

Many of the medium- to large-sized mammalian fossils indicate the earliest known occurrence of certain animals, such as several distant, smaller relatives of today's elephants, which evolved 7 million years earlier than previously thought. The team also found fossils that represent the latest known appearance by animals thought to be long extinct by this period, including the double-horned arsinoithere, an animal that resembled a modern rhinoceros. The new discoveries in the highlands also suggest that the animals had widespread habitats, the authors wrote.

Twenty-four million years ago, a permanent land bridge formed between Afro-Arabia and Eurasia, spawning a sudden burst in faunal diversity from migration. Prior to that major biogeographical event, animals in Afro-Arabia were thought to be evolving in isolation, but very little was known about them, Jaeger wrote. Researchers speculated that an earlier extinction event in Africa allowed the Eurasian animals to easily take over, Kappelman says. They suspected they had not yet found many fossils because, unlike the nearby East Africa Rift Zone, this area of Afro-Arabia was quiet tectonically and thus the fossils have not been exposed for discovery.

"Previously, we did not have any idea what had happened to these animals during this interval, or when, and the discovery helps to fill in these gaps," Kappelman says. The new findings suggest that there was no extinction event; instead, the animals were evolving and diversifying throughout the continent.

And many more surprising discoveries are to be expected, Jaeger wrote. While continuing to work on the vertebrate fossils, the researchers will soon be studying the myriad plant fossils they also found. Like the animals, Kappelman says, the record of plant evolution for Afro-Arabia is very sparse and a "missing years" story.

Megan Sever

Back to top