Geotimes

Feature

Geoarchaeology:

The Past Comes to Light

Geotimes Staff

Perhaps the only way to fully understand early humans is to understand their

ancient environments. That simple concept underlies the field of geoarchaeology — the application of the earth sciences to archaeological studies. The following

geoarchaeology vignettes show that geological stories are inseparable from the

human ones: Sea level can rise causing populations to migrate. A volcano can

erupt and wipe out a civilization. Climate can alter the soil and shift the

course of a culture. As the natural world changes, so too does society. Together,

geologists and archaeologists can unravel our past and better plan for and understand

our future.

Searching Dirt

Aegean Volcanic Dating Dilemma

Digging Below Manhattan

Black Sea Floods

Satellites Reconstruct Ancient Egypt

Iceman's Origins

SEARCHING

DIRT

For

25 years, geologist Rolfe Mandel has been studying early Americans. He wants

to know when they first arrived on the continent, where they came from and where

they went once they populated the landscape. But in searching for clues from

ancient people, Mandel decided on a route different from most archaeologists.

They go out looking for artifacts; he goes out looking for soils.

For

25 years, geologist Rolfe Mandel has been studying early Americans. He wants

to know when they first arrived on the continent, where they came from and where

they went once they populated the landscape. But in searching for clues from

ancient people, Mandel decided on a route different from most archaeologists.

They go out looking for artifacts; he goes out looking for soils.

Excavations in 2003 at the Claussen

site along Mill Creek in northeast Kansas revealed at least three archeaological

horizons. Rolfe Mandel, shown below inspecting mussel shells in an ancient campsite

buried 30 feet deep, now awaits radiocarbon dates for the lower two horizons.

Images courtesy of John Charlton, Kansas Geological Survey.

Mandel

diligently treks from creekbed to creekbed, searching the banks for layers of

soils that might be more than 9,000 years old, in hopes of finding evidence

of early Americans. He believes that Paleo-Indians spent most of their time

in stream valleys and near shallow depressions known as playas. As focal points

for water, animal and plant resources, the playas and streams were attractive

to people living in the High Plains. Because buried soils are viewable in river

cutbanks, Mandel says, the banks are like windows to ancient landscapes.

Mandel

diligently treks from creekbed to creekbed, searching the banks for layers of

soils that might be more than 9,000 years old, in hopes of finding evidence

of early Americans. He believes that Paleo-Indians spent most of their time

in stream valleys and near shallow depressions known as playas. As focal points

for water, animal and plant resources, the playas and streams were attractive

to people living in the High Plains. Because buried soils are viewable in river

cutbanks, Mandel says, the banks are like windows to ancient landscapes.

Ancient Americans are among the most elusive groups for archaeologists to study

because they were largely nomadic, following migrating herds of bison. They

left little behind in the way of belongings or settlements, Mandel says. So

archaeologists look for subtle clues of habitation, including flint spear points,

knife blades, charcoal remains of campfires and bone fragments from the game

that provided sustenance for the Paleo-Indians.

Until recently, most anthropologists believed that the peopling of North America

began about 11,500 years ago with the crossing of the Beringia land bridge and

then slow migration across the continent. However, archaeologists have now found

sites dating human activity to at least that age in the North American Southwest

and Southeast, which leads some researchers to believe that people arrived well

before then (see stories in this issue).

Mandel and colleagues at the University of Kansas department of anthropology

and the Kansas Geological Survey believe they will find evidence of inhabitants

from more than 11,500 years ago across the Great Plains. Art Bettis, a geologist

at the University of Iowa who also studies the peopling of the Great Plains,

says it is "very likely" that geoarchaeologists will find these older

sites.

Mandel, Bettis says, has developed the first comprehensive description of the

Quaternary landscape history of Kansas, which will help in the search for buried

archaeological sites. Indeed, Mandel's work is one of the most detailed regional

histories of Holocene environments in the world, echoes Lee Allison, head of

the Kansas Geological Survey. Having a good idea of what the ancient landscape

looked like, especially the temporal and spatial patterns of soil deposits,

allows Mandel to then target these geological oases for potential archaeological

evidence. "It is geologic exploration applied to an entirely new field,"

Allison says. Thus far, searching the soils has led Mandel and colleagues to

uncover several Paleo-Indian sites in Kansas that are at least 9,000 years old.

"Each site fills in a slightly different piece of the puzzle," Mandel

says. At the Kanorado site in northwestern Kansas, for example, researchers

uncovered well-preserved mammoth and camel bones at the base of a river cutbank

— thought to be more than 11,000 years old. And at the Winger site in southwestern

Kansas, researchers saw a massive bison bone-bed about 9 feet below the surface

along a stream that is cutting into a playa. Researchers have dated the bones

to about 9,000 years ago, and Mandel says there may be additional, older layers

below.

One spot to watch, Bettis says, is the Claussen site in northeastern Kansas,

which Mandel first discovered in 1999 but only recently began fully exploring.

Walking along a creekbed, 30 feet below the present-day land surface, Mandel

saw telltale signs of former stable landscapes — dark soil layers that

indicate buried topsoils. In the dark layers, he noted small flakes of flint,

cracked and blackened rocks from ancient fires, mussel shells and animal bone

fragments. At the very least, Mandel says, "someone had eaten dinner here

thousands of years ago." Even more exciting, he says, was that he could

see at least three distinct layers of human activity, with the upper layer dated

to nearly 9,000 years ago.

In the summer of 2003, Mandel and a team of archaeologists returned to the site,

armed with a $1 million endowment from retired geologist Joe Cramer (who has

spent more than a few years in search of ancient Americans himself) to search

for further evidence of human activity. They collected charcoal samples from

each distinct layer and sent them to a lab for radiocarbon dating. Now, Mandel

awaits word on the dating. In the meantime, he's going back out to the streambeds,

looking for archaeological evidence in the soils.

"Mandel's research into the early Americans promises to increase immensely

our understanding about the peopling of the Plains," Bettis says. Mandel

has changed the field of archaeology, he says, and it will be exciting to see

what comes next.

Megan Sever

Links:

"The

Ice-Free Corridor Revisited," Lionel E. Jackson Jr. and Michael C.

Wilson, Geotimes, February 2004

"Quest

for the Lost Land," Renée Hetherington et al., Geotimes,

February 2004

Back to top

Aegean

Volcanic Dating Dilemma

After a volcanic

eruption, widespread ash plumes can smother the region and leave behind valuable

marker horizons in the archaeological record. By assigning absolute dates to these

horizons, geologists are working with archaeologists to better understand the

history of the ancient civilizations that flourished nearby. At Thera, an eastern

Mediterranean island also known as Santorini, geologists are looking to the ash

to reconstruct what happened there thousands of years ago.

After a volcanic

eruption, widespread ash plumes can smother the region and leave behind valuable

marker horizons in the archaeological record. By assigning absolute dates to these

horizons, geologists are working with archaeologists to better understand the

history of the ancient civilizations that flourished nearby. At Thera, an eastern

Mediterranean island also known as Santorini, geologists are looking to the ash

to reconstruct what happened there thousands of years ago.

Floyd McCoy samples a small remnant of a

massively thick deposit left behind by the Late Bronze Age eruption of Thera in

the eastern Mediterranean. In the background stands the huge caldera excavated

by that eruption and now filled by the sea. Photo courtesy of Floyd McCoy.

Thera erupted more than 3,500 years ago, causing pyroclastic flows, earthquakes,

tsunamis and extensive tephra plumes that scattered pumice and ash as far away

as the Black Sea and the Nile Delta. In 1939, Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos

hypothesized that the Late Bronze Age eruption had led to the demise of the artistically

and technologically advanced Minoan civilization, which had thrived for more than

1,500 years on the Aegean island of Crete, just 70 kilometers south of Thera;

the civilization began to decline in 1450 BC. This idea quickly gained widespread

acceptance and was later popularized as proof of the historical accuracy of the

myth of Atlantis. However, a discrepancy between archaeological and geological

findings has led to a 20-year-long debate about the exact date of the eruption

and therefore, its role, if any, in the collapse of the Minoan civilization.

Traditional archaeological techniques of dating — such as synchronization with

Egyptian civilizations through the discovery of Minoan pottery at sites in the

Nile Valley or of Egyptian artifacts on Crete — have put the eruption date around

1550 B.C. or later. And some radiocarbon dates from the town of Akrotiri, a Theran

city buried under meters of ash, place it closer to 1500 B.C.

Other geological dating techniques have suggested a much earlier date for the

eruption. Acid snow and volcanic glass found in Greenland ice cores place the

date of the eruption around 1645 B.C. Also, thicker than normal tree rings found

in ancient trees in Anatolia show that a cool wet year, possibly caused by a massive

volcanic eruption, occurred around the same time. Additional evidence for climate

change at this time comes from Ireland, California and China.

"It's really geophysicists against archaeologists," says Floyd McCoy,

a volcanologist at the University of Hawaii who has been studying Thera for more

than 20 years. "But it's not a hostile thing. It's a wonderful kind of conversation

going on as we try to figure this out."

McCoy recently discovered 2-meterthick ash deposits in new roadcuts on the island

of Anaphi, 12 kilometers east of Santorini, and ash in seafloor cores close to

the Peloponnese peninsula. Both findings indicate a much wider ash distribution.

"This eruption was almost 10 times bigger than we thought," McCoy says.

"It had been about a 6. This puts it at 7.0" on the Volcanic Explosivity

Index, which ranges from 0 to 8. It would thus have had a more damaging and lasting

effect on the region's agriculture, trade, infrastructure and fleets, he says,

which could have eventually contributed to the Minoan collapse. "It's my

opinion that this eruption changed the whole course of Western civilization,"

McCoy says.

Jeremy Rutter, a specialist in Bronze Age archaeology of the Aegean at Dartmouth

College, agrees with the earlier date for the eruption, but he says that even

if the eruption were more explosive, the time span between the eruption and the

collapse of Minoan palatial civilization is still too long for it to be a factor.

"There's no way you're going to make something that happened in either 1640

B.C. or 1550 B.C. responsible for something that happened quite suddenly in 1450

B.C.," he says.

The true importance of the eruption date, Rutter says, is its potential for use

in correlating developments within various Bronze Age civilizations across the

eastern Mediterranean. "This is a problem that has been haunting this small

corner of scholarship for some time now," he says. "We're interested

in determining whether certain things happened first in Egypt or first in the

Aegean. And continuing disagreement over the absolute date of the Theran eruption

really is getting in the way of making progress on this."

Rutter said he expects the conflict will be resolved in the next 10 to 15 years,

with the discovery of Theran ash in a welldated archaeological site in the Near

East or by advances in dendrochronology. Or it could be solved geologically, McCoy

says. He is currently trying to apply new techniques for dating the eruption itself.

Sara Pratt

Geotimes contributing writer

Back to top

Digging

Below Manhattan

Buried under

the cement and concrete of the Manhattan skyline lie layers of glacial deposits,

animal bones and modern human detritus, representing thousands of years of Holocene

geology. The most urban setting in the world still provides opportunities for

geoarchaeological research, and recent work on the soils and stratigraphy of the

island sheds light on how to dig in New York.

Buried under

the cement and concrete of the Manhattan skyline lie layers of glacial deposits,

animal bones and modern human detritus, representing thousands of years of Holocene

geology. The most urban setting in the world still provides opportunities for

geoarchaeological research, and recent work on the soils and stratigraphy of the

island sheds light on how to dig in New York.

A trench at a dig site on Worth St. in downtown

Manhattan reveals soils and other geologic evidence for the ancient and more recent

history of New York. Image courtesy of Geoarcheology Research Associates.

Joseph Schuldenrein and his team of geoarchaeologists have further elucidated

Manhattan's geology, both prehistoric and historic. In the past few years, the

researchers were called in to several construction projects where they had a rare

opportunity to core and document profiles from freshly dug sites across lower

Manhattan.

They had seen these neighborhoods before, when centuries-old African-American

burial grounds were discovered during the construction of a tunnel almost two

decades ago. Schuldenrein, an adjunct professor at New York University, established

Geoarcheology Research Associates in 1989. Based in Riverdale, N.Y., the consulting

geoarchaeologists determine whether construction projects will disturb historic

sites and document the value of what might be found, necessary steps under the

National Historic Preservation Act. The company works to fuse geology and archaeology,

studying everything from early Native American landscapes in the Ohio River valley

to early cultures in Pakistan, India, and Jordan.

During their most recent opportunities to see under the city, the researchers

recorded some known stratigraphic history — from late Quaternary glacial moraine

deposits and prograding deltas to the arrival of the Dutch and the beginning of

anthropogenic landscape shifts. But they also found a soil horizon they could

follow across the island.

"Nobody knew about this soil," Schuldenrein says. The stable landform

serves as a baseline for future digging, allowing the team to reconstruct the

island's past surface morphology. It also provides a date for stratigraphic reference

from the layer's organic material, of about 2,000 years before present. Schuldenrein

presented the new soil horizon and a complete history of the island at last year's

annual Geological Society of America (GSA) meeting in Seattle, Wash.

Superimposing historic and current maps with well profiles, Schuldenrein's team

has painted "a real picture" of what to expect when digging, Schuldenrein

says. The least likely traces to be encountered are Native American, which Schuldenrein

compares to "looking for a needle in a haystack — they didn't leave much

behind." However, by reconstructing the postglacial landscape, he can point

to the stream deposits that represent landscapes where people might have made

camps or hunted in the region before the Dutch settlers came.

According to Dutch maps from the 1600s, a pond sat just north of the city's first

commons, where City Hall sits today, Schuldenrein says. Native Americans probably

stayed there, and the area held a local lime source from natural springs as well.

Several hundred years later, early American tanners used both the pond and the

lime.

"As the tanning industry got bigger and bigger, the pond became a huge cesspool,"

Schuldenrein says, creating a health epidemic (and a typhus reservoir). In 1815,

the city mandated its closure, filling it without leaving a trace. But Schuldenrein

traced the origins of the fill to an early artist's rendition of a nearby hill

that was once popular for sledding in the city. "The only thing this can

be is a glacial kame," or ridge deposited by a glacial stream, says Schuldenrein,

who has found oral accounts from 1850 describing the recreation area. "In

1815, that's what they used to fill it — they just leveled the landscape."

The new New Yorkers flattened glacial features and extended Manhattan to its current

configuration, changing the terminal moraine in order to create a huge commercial

center. Geoarcheology Research Associates has produced a 15,000-year chronology

and a map of lower Manhattan, noting the potential Dutch, English and American

archaeological sites and places where, hypothetically, Native Americans could

have settled.

Schuldenrein "mentally stripped away the construction and got to the landscape

as it was when people first settled there … defining some of the glacial

features underneath the city that influenced the settlement of the earliest European

historic populations," says David Cremeens, a soil scientist with GAI Consultants,

in Monroeville, Penn., and the chair of the archaeological geology division of

GSA.

Construction of the modern city disturbed previous deposits in some places and

preserved them under cement in others, also making the evidence hard to access,

Cremeens says. Schuldenrein's work could uncover social structures or other elements

buried underneath the modern city. It "has the potential of turning up something

brand new," he says, "or at least adding to what we know."

Naomi Lubick

Back to top

BLACK

SEA FLOODS

Born in Odessa,

Ukraine, Valentina Yanko-Hombach has always wanted to understand the ancient history

of the great basin that borders her homeland. The Black Sea, which stands as an

important trading and commercial center for the surrounding countries, holds clues

deep in its sediments about the people who once lived along its shores.

Born in Odessa,

Ukraine, Valentina Yanko-Hombach has always wanted to understand the ancient history

of the great basin that borders her homeland. The Black Sea, which stands as an

important trading and commercial center for the surrounding countries, holds clues

deep in its sediments about the people who once lived along its shores.

This SeaWiFS satellite pass over Turkey

in August 2000 highlights the Black Sea (top) and the nearby Mediterranean Sea.

A body of evidence is now emerging from Eastern European scientists about the

flooding history of the Black Sea, challenging a mainstream hypothesis of a large,

catastrophic flood linked to the biblical story of Noah’s flood. Provided

by ORBIMAGE and the SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center.

For the past 30 years, the geologist and micropaleontologist has been working

to reconstruct the region's sea level, drawing on research from other former-Soviet

and Eastern Bloc scientists. Language and political barriers have largely prevented

these scientists' data from entering the mainstream global scientific debate.

A prevailing Western idea about a past ancient flood in the region, first presented

in 1997 by Walter Pitman and Bill Ryan both of Columbia University, suggests that

salty Mediterranean water abruptly flooded the freshwater Black Sea about 7,200

years ago; the researchers link the event to the biblical story of Noah's flood.

But Yanko-Hombach is weaving together a different story for the basin — not

one of a single sharp cataclysmic inundation but instead of natural cyclicity.

The ups and downs of the sea could have mirrored the changes in culture for a

variety of societies.

She and colleagues have studied thousands of kilometers of high-resolution seismic

profiles and thousands of sediment cores during large-scale geological surveys

of the Black Sea shelf. Yanko-Hombach's own work hones in on foraminifera — shells

of bottom-dwelling microorganisms that reflect past water chemistry. She can match

specific species, for example, to the salinity signatures from various bodies

of water; some love saltwater, others abhor salt.

Yanko-Hombach's analyses suggest that the region has experienced many floods of

various magnitudes over the past 800,000 years. She has found a first wave of

recolonization by Mediterranean immigrants among foraminifera species in Black

Sea sediments as early as 9,500 years before present. Strontium isotope ratios

in mollusk shells, however, as measured by Candace Major and Steve Goldstein in

Ryan's research group, are now revealing the sudden switching on of a strong marine

signal at 8,400 years before present. Thus, Yanko-Hombach's data suggest an earlier

and less dramatic sea-level change. The evidence shows, Yanko-Hombach says, that

"Noah's flood legend has nothing to do with the Black Sea."

Ryan and Pitman's hypothesis was based on incomplete data, she says. The Black

Sea has many areas of regional washout, where sediments of certain ages are absent

and can give the impression of a flood event. Eastern scientists, however, have

long been sampling areas closer to the seashore.

Jim Teller of the University of Manitoba says that where researchers sample can

result in significantly different conclusions about changes the fossils underwent.

"Researchers get a limited number of dates, and there's a lot of difference

in the extrapolation process over intervals without dates," he says.

But Ryan speculates that the discrepancy with the Russian and Ukrainian measurements

may lie in the dating method itself. The ages Yanko-Hombach uses are primarily

derived from methods of carbon-14 dating. This technique required large samples,

he says, which may have introduced mixed organic materials and skewed the results

to older apparent ages.

"Her timing of the saltwater intrusion is more than a thousand years before

any similar salinity signal in cores calibrated with the new accelerator mass

spectrometer instruments," Ryan says. "So it is difficult for me to

see how so many salt-tolerant species of clear Mediterranean genesis could colonize

the Black Sea 9,500 years ago and yet not show up in the strontium isotopic signal."

Yanko-Hombach's data are "both wonderful and problematic," Ryan says,

pointing out that her "marvelously detailed record of the foraminifera species

abundances" still indicates the occurrence of an abrupt change in fauna in

some cores, just like what he sees in the bottom-dwelling mollusks. "A flood

from the Mediterranean could produce this change, but the real issue is whether

a flood is the required causative event or if something of less magnitude and

more gradual could produce the changes we both observe," he says.

Currently, Yanko-Hombach and Ryan are working together to apply modern dating

methods to single specimens in an old Ukrainian core sample. Ryan says that his

research has involved frequent correspondence with Eastern scientists. Yanko-Hombach's work, he says, is a valuable service to the community in creating new

opportunities for collaborative study.

"I am trying to bring together people to develop scientific dialogue,"

Yanko-Hombach says. She has already presented her research widely, including at

a NATO workshop last October in Bucharest, Romania, and the Geological Society

of America (GSA) meeting last November in Seattle, where she co-chaired a session

about the Black Sea.

To further break down barriers of the past, she has proposed a 4.5 million Euro

proposal to the European Union that involves archaeologists, anthropologists and

geologists from 11 countries, including Germany, Switzerland, France, Italy and

those bordering the Black Sea basin (excluding Georgia). The project would continue

her quest to link climate to changes in coastal migration and culture in the region.

In the meantime, archaeologists continue their own quest to link their findings

to flood events. Archaeological evidence from a site called Kamennaya Balka in

Rostov, Russia, for example, supports a large flooding event 16,000 and 14,000

years before present, Yanko-Hombach says. She and Andrey Tchepalyga of the Institute

of Geography in Moscow say that melting glaciers and thawing permafrost caused

the Caspian Sea to increase its surface level by about 80 meters, swelling to

half again its present size, and to spill multiple times into the Black Sea during

the 2,000-year period.

Nataly Leonova at Moscow State University suggests that such flooding may have

been responsible for local changes in culture about 16,000 years ago. Before that

time, Leonova says that archaeological artifacts in and around the Crimea indicate

a clear relationship to Caucasus cultures. And then that connection suddenly stopped:

The area was perhaps covered by water, cutting off communication.

All the floods likely caused some change in culture, Yanko-Hombach says. Flooding

can happen in many places in the world as a result of climate change, and thousands

of years ago, "local people would have considered this as 'Noah's flood,'"

she says.

"These were magical kinds of things, so anything truly larger compared to

your experiences and what your ancestors had told you about would be worth writing

down," says Teller, who also co-chaired the GSA session. He has published

work in 2000 suggesting that Noah's flood occurred in the Persian Gulf, where

archaeologists found the Epic of Gilgamesh — clay tablets that include a story

of a great flood.

Still, Teller says that linking any flood event to Noah's flood is nearly impossible

at this time "unless something is discovered that nails down the whole concept

of Noah's flood — which is just a few verses in the Bible."

Lisa M. Pinsker

Back to top

Satellites

Reconstruct Ancient Egypt

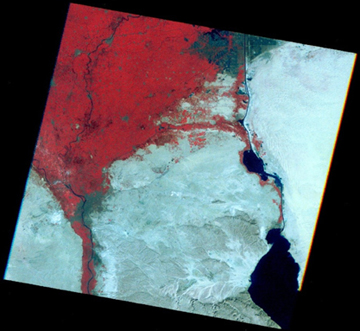

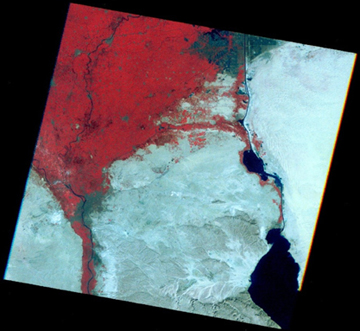

Sarah

Parcak of Cambridge University in England used this Landsat image of the eastern

Egyptian delta to locate 44 new archaeological sites in Egypt. Darker spots

on the image reveal archaeological sites and modern cities from the surrounding

landscape due to their higher moisture content.

Sarah

Parcak of Cambridge University in England used this Landsat image of the eastern

Egyptian delta to locate 44 new archaeological sites in Egypt. Darker spots

on the image reveal archaeological sites and modern cities from the surrounding

landscape due to their higher moisture content.

Parcak is taking this satellite imagery and verifying it with archaeological

data and cores from the delta in order to differentiate present-day cities from

the ancient sites, and to reconstruct settlements from Egypt's Old Kingdom —

best known for the Great Pyramids. This is the first time this methodology has

been used to locate archaeological sites.

Presenting at the American Geophysical Union meeting last December, Parcak says

she particularly wants to see how an extreme and sustained period of drought

and cooling 4,200 years before present affected the delta landscape and the

people of the Old Kingdom. Archaeologists have found many sites tied to the

Old Kingdom from before the abrupt climate change, but very few after. Thus

Parcak's research could open up the field for further research on climate change-civilization

interaction.

Megan Sever

Back to top

ICEMAN'S ORIGINS

A long the Italian-Austrian border in 1991, two German hikers made a startling

discovery: a 5,200-year-old mummy preserved in an alpine glacier. Later named

the Iceman, this Neolithic man has led to a plethora of research and debate over

the past 13 years, speculating about his lifestyle, habitat and cause of death.

The Iceman, however, left clues about his life and habitat in the chemical composition

of his remains. Through food and drink, the isotopic signatures from local rocks,

soils and water transfer to the biological minerals deposited in the human body.

Tooth enamel preserves childhood activity, and bones reveal the last 10 to 20

years before death. By comparing the Iceman's isotopic signatures to those in

the surrounding environment, geoscientists now say that they have nailed down

his likely birthplace and lifelong travel patterns.

The Iceman, also known as Ötzi (he was found in the Ötzal Alps), probably

lived his entire life — 46 years — within a 37-mile range south of the glacier

in which he was found, says Wolfgang Müller, a geologist at the Australian

National University. His birthplace was likely within a few valleys to the southeast

of where he was found — present-day northernmost Italy. He migrated during his

later adult life and seemed to spend much of his adult life a bit farther west,

Müller and colleagues suggest in an article in the Oct. 31 Science.

While Ötzi may have migrated seasonally, the evidence that he spent his entire

life in one small region demonstrates that central Europe's Alpine valleys were

permanently inhabited during the terminal Neolithic, Müller and colleagues

write.

"Knowing the Iceman's home territory will help in reconstructing the cultural

landscape in which the Iceman lived," says Thomas Loy, an archaeologist at

the University of Queensland in Australia, who has been using DNA analysis to

understand the Iceman's death (most recently speculated to have been caused by

a violent battle). Until Müller's analysis, Loy says, the Iceman was a singularity;

he was an isolated Copper Age person with no corresponding identifiable culture.

The researchers compared isotopic composition in Ötzi's teeth and bones with

soils throughout the region. Within his habitat, at least four different types

of rock are distinguishable by strontium and lead isotopes: limestone, rhyolite,

basalt and a group of mixed phyllites and gneisses. Also in his teeth and bones,

the geochemists noted distinct levels of certain oxygen isotopes that they could

then compare to known oxygen isotopes in the area, thus constraining Ötzi

to the specific watersheds in which he lived at varying stages of his life.

Although much of Müller and colleagues' findings correspond to previous research

in the region, some papers have suggested that Iceman spent a good deal of time

farther north than Müller's team suggests. But, Müller says, all the

isotopic evidence they found points to the south. In addition, the isotopic evidence

corresponds to the botanical and archaeological evidence.

In the new study, the scientists use a "combination of several techniques

pooled together to maximize information, and also new methods never utilized in

such circumstances," Müller says. One such method involves examining

argon isotopes in tiny mica flakes found in the Iceman's intestines, which constrains

his last meal to a region that holds the same mica. Loy says using combined isotopic

evidence to constrain habitat and travel ranges is "a very powerful method,"

and will be a very useful tool to investigate prehistoric people and societies.

Megan Sever

Back to top

For

25 years, geologist Rolfe Mandel has been studying early Americans. He wants

to know when they first arrived on the continent, where they came from and where

they went once they populated the landscape. But in searching for clues from

ancient people, Mandel decided on a route different from most archaeologists.

They go out looking for artifacts; he goes out looking for soils.

For

25 years, geologist Rolfe Mandel has been studying early Americans. He wants

to know when they first arrived on the continent, where they came from and where

they went once they populated the landscape. But in searching for clues from

ancient people, Mandel decided on a route different from most archaeologists.

They go out looking for artifacts; he goes out looking for soils.

Mandel

diligently treks from creekbed to creekbed, searching the banks for layers of

soils that might be more than 9,000 years old, in hopes of finding evidence

of early Americans. He believes that Paleo-Indians spent most of their time

in stream valleys and near shallow depressions known as playas. As focal points

for water, animal and plant resources, the playas and streams were attractive

to people living in the High Plains. Because buried soils are viewable in river

cutbanks, Mandel says, the banks are like windows to ancient landscapes.

Mandel

diligently treks from creekbed to creekbed, searching the banks for layers of

soils that might be more than 9,000 years old, in hopes of finding evidence

of early Americans. He believes that Paleo-Indians spent most of their time

in stream valleys and near shallow depressions known as playas. As focal points

for water, animal and plant resources, the playas and streams were attractive

to people living in the High Plains. Because buried soils are viewable in river

cutbanks, Mandel says, the banks are like windows to ancient landscapes.  After a volcanic

eruption, widespread ash plumes can smother the region and leave behind valuable

marker horizons in the archaeological record. By assigning absolute dates to these

horizons, geologists are working with archaeologists to better understand the

history of the ancient civilizations that flourished nearby. At Thera, an eastern

Mediterranean island also known as Santorini, geologists are looking to the ash

to reconstruct what happened there thousands of years ago.

After a volcanic

eruption, widespread ash plumes can smother the region and leave behind valuable

marker horizons in the archaeological record. By assigning absolute dates to these

horizons, geologists are working with archaeologists to better understand the

history of the ancient civilizations that flourished nearby. At Thera, an eastern

Mediterranean island also known as Santorini, geologists are looking to the ash

to reconstruct what happened there thousands of years ago.  Buried under

the cement and concrete of the Manhattan skyline lie layers of glacial deposits,

animal bones and modern human detritus, representing thousands of years of Holocene

geology. The most urban setting in the world still provides opportunities for

geoarchaeological research, and recent work on the soils and stratigraphy of the

island sheds light on how to dig in New York.

Buried under

the cement and concrete of the Manhattan skyline lie layers of glacial deposits,

animal bones and modern human detritus, representing thousands of years of Holocene

geology. The most urban setting in the world still provides opportunities for

geoarchaeological research, and recent work on the soils and stratigraphy of the

island sheds light on how to dig in New York.  Born in Odessa,

Ukraine, Valentina Yanko-Hombach has always wanted to understand the ancient history

of the great basin that borders her homeland. The Black Sea, which stands as an

important trading and commercial center for the surrounding countries, holds clues

deep in its sediments about the people who once lived along its shores.

Born in Odessa,

Ukraine, Valentina Yanko-Hombach has always wanted to understand the ancient history

of the great basin that borders her homeland. The Black Sea, which stands as an

important trading and commercial center for the surrounding countries, holds clues

deep in its sediments about the people who once lived along its shores.  Sarah

Parcak of Cambridge University in England used this Landsat image of the eastern

Egyptian delta to locate 44 new archaeological sites in Egypt. Darker spots

on the image reveal archaeological sites and modern cities from the surrounding

landscape due to their higher moisture content.

Sarah

Parcak of Cambridge University in England used this Landsat image of the eastern

Egyptian delta to locate 44 new archaeological sites in Egypt. Darker spots

on the image reveal archaeological sites and modern cities from the surrounding

landscape due to their higher moisture content.