Geotimes

Untitled Document

News Notes

Planetary geology

Tiny moon, gigantic geyser

A tiny moon

of Saturn, no larger than England, is changing researchers’ notions about

which celestial bodies can support geologic activity. New, closer images of

Enceladus have confirmed that a plume, noticed in previous images, is indeed

an enormous geyser emanating from visible cracks in the moon’s surface.

A tiny moon

of Saturn, no larger than England, is changing researchers’ notions about

which celestial bodies can support geologic activity. New, closer images of

Enceladus have confirmed that a plume, noticed in previous images, is indeed

an enormous geyser emanating from visible cracks in the moon’s surface.

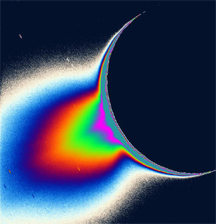

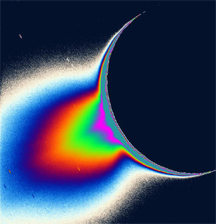

In this color-enhanced image, an enormous

plume emanating from fractures on Saturn’s moon Enceladus appears backlit

by the sun. Astronomers were surprised to find geologic activity on the small

moon, which is seven times smaller than Earth’s moon. Image courtesy of

NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft first revealed the plume-like feature in images

taken in January and February last year. But according to Carolyn Porco, Cassini

imaging team leader at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., speculation

remained that the feature was an artifact of the camera. Following a special

Cassini mission in November to take a closer look, however, the images “confirmed

it without question,” Porco says.

The moon and its plume look similar to a comet and its tail, which forms from

vapor created when sunlight warms the icy body. Enceladus, however, does not

receive much sunlight. Instead, pressurized vapor on Enceladus emanates from

below the surface and “shoots out like a jet” through vents the team

calls tiger stripes, Porco says. She describes the vapor’s composition

of small icy particles to be “like the finest powder you might ski on in

Utah.” The cause of the pressurized geyser, Porco says, is due to an internal

source of heat on the moon, either from flexing tides or from radioactive material.

Small bodies such as Earth’s moon, which is 3,476 kilometers in diameter,

typically lose their internal heat shortly after formation, rendering them geologically

dead. Porco says that even though she was not surprised to find geologic activity

on Enceladus, she finds it “thrilling” to see geologic activity on

another body — especially a moon only 480 kilometers in diameter, with

a geyser as tall as the moon is wide. Finding activity on such a small body,

Porco says, “has torqued our ideas around about how geologic activity can

come about.”

Kathryn Hansen

Back to top

Untitled Document

A tiny moon

of Saturn, no larger than England, is changing researchers’ notions about

which celestial bodies can support geologic activity. New, closer images of

Enceladus have confirmed that a plume, noticed in previous images, is indeed

an enormous geyser emanating from visible cracks in the moon’s surface.

A tiny moon

of Saturn, no larger than England, is changing researchers’ notions about

which celestial bodies can support geologic activity. New, closer images of

Enceladus have confirmed that a plume, noticed in previous images, is indeed

an enormous geyser emanating from visible cracks in the moon’s surface.