Fortunately, Nittrouer and fellow earth science graduate students had a department to return to when classes resumed Jan. 17 — not all Tulane students were as lucky. University officials decided that to keep afloat financially, they would have to make cuts, including eliminating the civil, environmental and electrical engineering departments, as well as computer science. Tulane’s return to normalcy, however, will take time and the continued aid from other universities, some of which are also working to recover from the disaster.

Among Louisiana’s major universities, Tulane suffered some of the most severe damage from Hurricane Katrina. Flood-water reached levels between 60 and 120 centimeters (2 to 4 feet) high at the back of campus, where several science facilities are located, including the biomedical labs. The earth science department in the front part of campus stayed dry, however, suffering only wind damage.

Stephen Nelson, a volcanologist and chair of Tulane’s earth science department, says that he “wasn’t all that concerned” that his department would be cut, as the department’s numbers appear to remain strong. As a private university, Tulane strongly depends on tuition, Nelson says. Departments with fewer students, such as in the engineering school, have always faced more of a funding challenge because it’s “difficult for them to pay their own way,” Nelson says. As a result, the engineering department has historically been heavily subsidized by the rest of the university, and was an easy target for cuts post-Katrina.

Prior

to Katrina, the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences had good numbers

compared to other departments at Tulane, with about 10 undergraduate students,

28 graduate students and 10 faculty members, but it remains unknown how many

will return this semester. Nelson expects that most of the undergraduates will

return, but has heard that five or six graduate students left and two faculty

members resigned.

Prior

to Katrina, the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences had good numbers

compared to other departments at Tulane, with about 10 undergraduate students,

28 graduate students and 10 faculty members, but it remains unknown how many

will return this semester. Nelson expects that most of the undergraduates will

return, but has heard that five or six graduate students left and two faculty

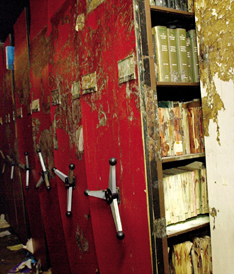

members resigned. These books at Tulane University’s library suffered severe water damage from Hurricane Katrina. University personnel continue to sort through books, microfilm and government documents, some of which are irreplaceable. Image courtesy of P. Burch, Tulane University Publications.

While Tulane was out of commission, most students found other universities to take them in, Nelson says. Graduate student Nittrouer, for example, spent three months at the University of Washington’s oceanography department in Seattle following a brief return to New Orleans to retrieve his computer and other belongings from his apartment, which to his relief had survived the hurricane.

Other Tulane earth science students stayed closer to home, attending classes at Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge as a small part of the total 3,000 students that the university took in. LSU was not damaged by the hurricane, according to Laurie Anderson, chair of the Geology and Geophysics department at LSU. As a result, Anderson says, the campus “became a major hub” for the emergency response that included an 800-bed field hospital and animal shelter.

LSU also supported earth science students from the University of New Orleans (UNO), which closed for a semester following Hurricane Katrina. Most buildings on the UNO campus reopened the first week of January, but the earth science department still awaited inspection for electrical problems, according to Denise Reed, a geoscience professor at UNO. Those inspections could delay the department’s opening, Reed says. Severe flooding of surrounding low-lying apartments and houses, however, posed a larger problem for the school than damage to the university, which sits atop a hill, Reed says. UNO officials are concerned that students and faculty, without a place to live, might not return to the school.

Still, the earth science department at UNO, which, like Tulane, depends heavily on student tuition, has survived intact without any cuts thus far. That’s because the university has been working hard to retain students, Reed says. Although the department was physically closed last semester, students could continue taking courses that Reed and others taught through intensified online curricula — one student, Reed notes, worked from as far away as Nigeria. UNO is also combating the potential loss of students and faculty by arranging temporary trailer housing on campus.

ExxonMobil is also helping UNO recover. Each year, the company donates money to the earth science programs to support minority education and outreach to high school students. This year, ExxonMobil doubled their contribution to $100,000, to help earth science students return to UNO, Reed says.

Of the total university’s average of 15,000 to 17,000 students, Reed says that 12,000 must remain enrolled to avoid cuts due to budget stress. As of early January, only two-thirds of that number had registered.

In the meantime at Tulane, Nelson has been preparing for upcoming classes. The natural disasters class that he teaches, for example, will include an added focus on the local geology for the first time. “I do my research in places where there are mountains; I come from places where there are mountains,” Nelson says. “I have been here for 25 years and have pretty much ignored the geology of New Orleans.”

In November, however, Nelson started offering public field trips to see the geology that Katrina “brought back to the surface,” such as sand deposits and the cross-bedding of those deposits exposed by bulldozers recreating streets. Nelson plans to incorporate these trips into his class because he says that geology is important to people’s understanding of what happened in New Orleans and south Louisiana.

“In New Orleans, we have to send out two messages,” Nelson says. “One, we’re back in business, and two, we really need further help here because there is so much devastation still existing.”

Amid the devastation, the biggest challenge in getting the Tulane earth science department up and running, Nelson says, has been trying to accommodate students’ needs with a reduced number of faculty and graduate students to teach. Graduate student Nittrouer, who plans to reschedule the defense of his thesis in the coming months, says that “if things look really dire,” he will be happy to help teach for the department that he says “does a lot of work and a lot of good things.”

Tulane University student Jeffery Nittrouer was only a few weeks from

defending his master’s thesis — studying the movement of streambed materials

in the Mississippi River — when Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Louisiana

coast Aug. 29. Attending a conference in New Zealand thousands of miles away from

his New Orleans school, Nittrouer avoided evacuation hassles. But he did not know

whether years of his research and data in the Department of Earth and Environmental

Sciences, or even his apartment, had survived. “It was pretty hairy there

for a little while,” Nittrouer says.

Tulane University student Jeffery Nittrouer was only a few weeks from

defending his master’s thesis — studying the movement of streambed materials

in the Mississippi River — when Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Louisiana

coast Aug. 29. Attending a conference in New Zealand thousands of miles away from

his New Orleans school, Nittrouer avoided evacuation hassles. But he did not know

whether years of his research and data in the Department of Earth and Environmental

Sciences, or even his apartment, had survived. “It was pretty hairy there

for a little while,” Nittrouer says.