Geotimes

Untitled Document

Geophenomena

A far-off new ocean

Longer to patch the ozone hole

A far-off

new ocean

A new

ocean basin opened up in an African desert last fall, or at least, made its

first cracks. The ruptures, researchers say, could mark the beginning of an

inland sea in Ethiopia’s East African rift zone.

A new

ocean basin opened up in an African desert last fall, or at least, made its

first cracks. The ruptures, researchers say, could mark the beginning of an

inland sea in Ethiopia’s East African rift zone.

This 6-meter-wide fissure in Ethiopia’s

East African rift zone spouted ash after earthquakes shook the region, in what

may be the first visible events leading to ocean spreading in the rift. Image

courtesy of Cynthia Ebinger.

In September, a large earthquake followed by a series of tremors shook the region,

and about a week later, a segment of the rift spewed ash in a volcanic eruption

and tore several cracks amounting to an opening of more than 6 meters at the

surface, according to Cynthia Ebinger, a geologist at Royal Holloway University

of London. “It appears that we’ve seen the birth of an ocean basin,”

she told the BBC Dec. 8.

The new opening is part of the Afar triple junction (also sometimes called the

Gulf of Aden triple junction), where the Arabian and African plates come together

at a point where Africa is also splitting. The newly active portion of the basin,

about 20 kilometers wide and 60 kilometers long, is fractured by a series of

1.8-million-year-old faults, with the new fissures splitting it further. Researchers

hailing from a variety of institutions, including Royal Holloway University

of London, University of Oxford and Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, have

tracked strain and movement in the region with seismic arrays as well as by

satellite. Taken together with eyewitness accounts, the data, presented by the

researchers at the American Geophysical Union annual meeting in San Francisco

in December, suggest that the system is transitioning between continental rifting

to oceanic spreading, accompanied by changes in the rocks beneath.

Hot magma from the mantle welling up under the southern part of the zone may

be facilitating the rifting, members of the research group suggested, in a region

where tectonic forces are too small to explain the rifting occurring now. Although

this may be the first time human eyes have observed such speedy and perceptible

rifting, it will take millions of years for a true ocean to develop here: Researchers

predicted that the rift will continue to pull apart very slowly, at around 6

millimeters per year.

Naomi Lubick

Back to top

Longer

to patch the ozone hole

Longer

to patch the ozone hole

Scientists predicted in 2002 that the atmosphere’s ozone “holes”

would recover to 1980 levels by 2050. But new research shows the ozone layer will

take 15 years longer to heal than previously thought.

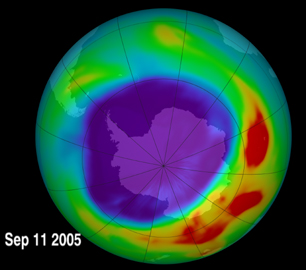

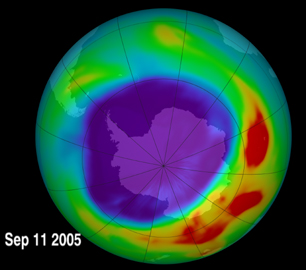

Not quite a “hole,” ozone depletion

in the Antarctic reaches its maximum from August to October every year. Last year,

the peak occurred Sept. 11, shown here in blue, slightly larger than the maximum

depletion in 2004 — but almost 2 million square kilometers smaller than the

largest ever measured in 1998, which averaged about 26 million square kilometers.

Scientists announced revised recovery dates for the ozone holes at both poles

in December. Image courtesy of NASA/GSFC.

After the discovery of an ozone hole in the Antarctic in 1985, researchers determined

that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halon gases had destroyed ozone in a layer

that protects Earth from ultraviolet rays, over both the Arctic and Antarctic.

International efforts taken in 1996 to stop the manufacture and use of CFCs had

dramatically reduced the amount of the substances, which travel into the lower

atmosphere. There, strong ultraviolet light breaks up the molecules, freeing chlorine,

which can destroy ozone.

Despite the ban on CFCs, new research shows that emissions of the molecules in

2003 from the United States and Canada still ranged from 10 to 45 percent of the

global total, according to Dale Hurst of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA) Global Monitoring Division in Boulder, Colo., and his co-workers.

Hurst hypothesizes that in addition to continued manufacture and use in developing

countries, remaining pools of CFCs in old appliances and even car air conditioners

are enough to extend the damaging effects of the chemical by a decade and a half

more than modelers previously thought. More CFCs may also come from sources squirreled

away after manufacturing officially ended, he said in a Dec. 6 presentation at

the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in San Francisco.

The ozone hole in the Antarctic reached its maximum last year on Sept. 11, when

temperature conditions and chemical concentrations hit their prime during the

Antarctic spring, according to Michelle Santee of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

in Pasadena, Calif. Using NASA’s Aura satellite, which has been tracking

global ozone levels and other ozone-depleting chemicals since its launch in 2004,

Santee and co-workers have determined that seasonal changes in ozone levels vary

at the north and south poles.

Monitoring so far, she said at the AGU meeting, shows that the Arctic gets warm

enough so that chlorine-containing molecules have less of a destructive effect

than in Antarctica, where it is cold enough to maintain the chemical reactions

that destroy ozone year-round. But wind patterns in the Arctic also disperse chemicals

and ozone, enough so that the status of ozone at the northern pole remains unclear,

Santee said.

The condition of the Arctic, where the ozone hole may mend by 2030 or 2040, still

seems likely to improve more rapidly than at the southern pole, according to John

Austin of NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory at Princeton University

in New Jersey. The Antarctic hole most likely will not recover until 2065, but

even that prediction remains subject to the variability in chemistry and the two

polar environments.

Naomi Lubick

Back to top

Untitled Document

A new

ocean basin opened up in an African desert last fall, or at least, made its

first cracks. The ruptures, researchers say, could mark the beginning of an

inland sea in Ethiopia’s East African rift zone.

A new

ocean basin opened up in an African desert last fall, or at least, made its

first cracks. The ruptures, researchers say, could mark the beginning of an

inland sea in Ethiopia’s East African rift zone. Longer

to patch the ozone hole

Longer

to patch the ozone hole