geotimesheader

News Notes

Global change

Laughing

gas throws a hard punch

A shocking amount of nitrous oxide off the

western coast of India is causing scientists to take another look at laughing

gas. Researchers at the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa found

three times more nitrous oxide in the Arabian Sea than previously found

anywhere else in the world.

“The actual magnitude of the concentrations really blew me away,” says

Louis Codispoti of Horn Point Laboratory in Cambridge, Md., who read the

report in the Nov. 16 Nature. The findings also suggest nitrous

oxide plays a stronger role in global warming than originally thought.

“We

are talking about a fairly large and globally significant source,” says

Wajih Naqvi, the primary author of the report. The contribution of the

Arabian Sea to the total amount of nitrous oxide into the atmosphere may

be as much as one million tons per year or 25 percent of all anthropogenic

sources of nitrous oxide, he says. This complicates the picture of global

warming even further. “On a per molecule basis, nitrous oxide is over 200

times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation as carbon dioxide.”

Even small increases in nitrous oxide inventory of the atmosphere could

bring about relatively large changes in climate.

“We

are talking about a fairly large and globally significant source,” says

Wajih Naqvi, the primary author of the report. The contribution of the

Arabian Sea to the total amount of nitrous oxide into the atmosphere may

be as much as one million tons per year or 25 percent of all anthropogenic

sources of nitrous oxide, he says. This complicates the picture of global

warming even further. “On a per molecule basis, nitrous oxide is over 200

times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation as carbon dioxide.”

Even small increases in nitrous oxide inventory of the atmosphere could

bring about relatively large changes in climate.

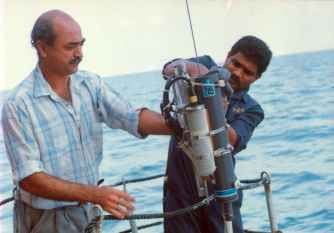

[Wajih Naqvi (left) and

assistant prepare a water trap while on board the Research Vessel Sagar

Kanya (below right). Photos courtesy of W. Naqvi.]

A 1992 report of nitrous oxide concentrations of 173 nanomoles off the

coast of Peru held the record. Naqvi’s report, with nitrous oxide concentrations

reaching 533 nanomoles in the Arabian Sea, triples that number. During

the summer monsoon season, an undercurrent off the coastal shelf of western

India brings an upwelling of cold, saline, nutrient rich and oxygen depleted

water to the country’s shores. But freshwater runoff during the heavy monsoon

rains bleeds out over the colder seawater — covering it with a 5- to 10-meter-thick,

warm cap. Planktonic algae thrive in the upper layers of these nutrient

rich waters before sinking to the bottom where bacteria, living off decaying

organic matter, produce nitrous oxide in the low-oxygen environment through

both nitrification and denitrification.

The three-year study also indicates fertilizer runoff into the Arabian

Sea may be contributing to the production of the nitrous oxide. The increasing

runoff of nutrients from land aggravate the situation by increasing eutrophication

in the surface waters and thereby feeding the bacteria with further organic

matter. Because the area is so shallow, 6 to 28 meters, the nitrous oxide

produced can easily escape to the atmosphere, Naqvi says. More nitrous

oxide could feed a vicious cycle — leading to increased global warming,

potentially stronger monsoons, an increase in the nitrogen-laden runoff

from land, coastal eutrophication, and bacteria producing nitrous oxide

as they munch on dead plankton cells. And nitrous oxide is but one part

in the “deliciously complex” nitrogen cycle, Codispoti says.

In the open ocean, the site of past studies on nitrous oxide, scientists

such as Codispoti learned that bacteria finish eating what little oxygen

remains in their surroundings and then begin to consume the nitrous oxide

they already produced — converting N2O to N2 using an enzyme known as nitrous

oxide reductase in the denitrification process. The bacteria switch to

consuming the reductase — helping to keep the level of nitrous oxide in

check.

Naqvi and colleagues have found that in shallow waters with almost no

oxygen, high microbial metabolic rates can lead to brief periods when nitrous

oxide accumulates to extremely high levels with the chance, in the shallow

environment, to escape before the bacteria can chow down on the nitrous

oxide reductase. This can give a pulsing effect to the levels of nitrous

oxide as the stop-and-go nature of local phenomena, such as storms, temporarily

re-oxygenate the waters.

“It’s time we started looking at analogous areas more closely,” Codispoti

says. He would like to investigate nitrous oxide in the Chesapeake Bay.

Other areas with fluctuating nutrient zones to explore include the mouth

of the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico and coastal waters off Peru.

Christina Reed

“We

are talking about a fairly large and globally significant source,” says

Wajih Naqvi, the primary author of the report. The contribution of the

Arabian Sea to the total amount of nitrous oxide into the atmosphere may

be as much as one million tons per year or 25 percent of all anthropogenic

sources of nitrous oxide, he says. This complicates the picture of global

warming even further. “On a per molecule basis, nitrous oxide is over 200

times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation as carbon dioxide.”

Even small increases in nitrous oxide inventory of the atmosphere could

bring about relatively large changes in climate.

“We

are talking about a fairly large and globally significant source,” says

Wajih Naqvi, the primary author of the report. The contribution of the

Arabian Sea to the total amount of nitrous oxide into the atmosphere may

be as much as one million tons per year or 25 percent of all anthropogenic

sources of nitrous oxide, he says. This complicates the picture of global

warming even further. “On a per molecule basis, nitrous oxide is over 200

times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation as carbon dioxide.”

Even small increases in nitrous oxide inventory of the atmosphere could

bring about relatively large changes in climate.