Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers

| Geotimes Home | Calendar | Classifieds | Subscribe | Advertise |

| Geotimes

Published by the American Geological Institute |

January

2001

Newsmagazine of the Earth Sciences |

NASA

has revised its Mars program for the next several decades, dropping some

missions altogether and leaving scientists in the lurch. Less than six

months ago, NASA had ambitious plans to send a lander to Mars in 2001 and

another in 2003 to collect rock samples. Many planetary geologists were

working on the instruments that would allow those missions to happen.

NASA

has revised its Mars program for the next several decades, dropping some

missions altogether and leaving scientists in the lurch. Less than six

months ago, NASA had ambitious plans to send a lander to Mars in 2001 and

another in 2003 to collect rock samples. Many planetary geologists were

working on the instruments that would allow those missions to happen.

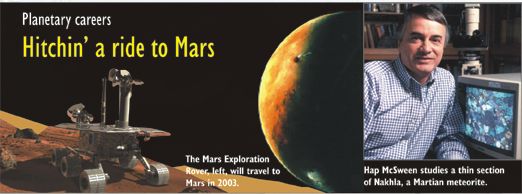

The failure of the Mars Polar Lander mission in 1999 left NASA reluctant to press on with an optimistic sample return mission and the launch of a lander whose design was all too similar to the lost Polar Lander. Last spring, NASA cancelled the lander but kept the orbiter for the Mars Odyssey 2001 mission and, in July, postponed sample returns until 2011 in favor of the 2003 Mars Exploration twin rovers. Those who worked on the scrapped missions are now embarking on uncertain paths that involve a bit of luck and a lot of hope that their instruments will be incorporated into the new missions.

As one of the principal investigators for the science payload of the

original 2001 Mars Surveyor mission and 2003 sample return, Steven Squyres

of Cornell University had a lot to lose when those missions were erased.

Fortunately for Squyres, his team was involved in early investigations

of an airbag-deployed rover. When the old plans were scrapped, the air

bag-deployed rovers were on a list of about a hundred other ideas for future

Mars ventures intended to replace the cancelled missions.

NASA had to move fast if it was going to get plans underway to take

advantage of the 2003 launch opportunity, when spacecraft can most easily

be sent to Mars. His team’s rover and science payload made the cut and

plans are now underway to build twin “robotic field geologists” for the

2003 mission. “My team was very lucky,” Squyres says. “There are several

others whose instruments do not have a ride to Mars.” Squyres is now the

principal investigator for the science payload for the 2003 mission.

David Kaplan is still working for NASA but his instrument was left

to collect dust when the original 2003 mission was cancelled. Kaplan developed

an instrument that would have produced rocket fuel — pure propellant-grade

oxygen — from carbon dioxide in Mars’ atmosphere. It was certified for

flight but has now found what will probably be its permanent home: a controlled-environment

storage facility at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Kaplan has

since taken a year of leave from Johnson Space Center to work at NASA headquarters

in the Office of Space Flight developing technologies for human trips to

Mars. The next chance for his rocket fuel payload to hitch a ride to Mars

is 2007. But by then, the payload he originally designed in 1997 will be

out of date. “I’m quite certain they won’t take old payloads out of the

vault,” he says.

Several other teams have developed instruments housed by cancelled

landers. Thomas Meloy of West Virginia University was also a principal

investigator for the cancelled Mars missions. The instruments he designed

to determine the mineral composition of martian soil will not go to Mars

in 2003 or 2005. He continues to work on these instruments with the hope

that they might hitch a ride on the Mega Rover 2007 mission, but NASA officials

have not guaranteed his work a spot on the spacecraft. Already in his 80s,

Meloy has other concerns. “How can I know that I’ll live until 2011 or

2012 so that I’ll be able to publish all the data?” he asks. “But on the

upside, we’ll have far better instruments [in 2007].”

To survive mission cancellations with the fewest bruises, it seems

that building a specific instrument is not the safest way to go. Hap McSween

of the University of Tennessee has spent his career studying martian meteorites

and was one of the first tapped by NASA to become a part of its science

team back in the early 1980s.

“I was at the right place at the right time. It was blind luck,” McSween

says. Now that studying Mars has become more popular, it has become increasingly

difficult to secure a spot in the planning for NASA’s Mars missions. Most

of McSween’s involvement with NASA over the past years has been as a generalist

on the science team, helping to interpret chemical and other data to determine

the mineral composition of Mars. He will work on the Mars Odyssey

2001 mission interpreting mineralogy and petrology from thermal imaging

data. What he learns will apply to the planned 2011 sample return.

But like others, McSween would like to see martian rocks delivered

to Earth sooner. “I appreciate that we have to be very careful, but I’m

really disappointed,” he says. “I’ll find something to do in the meantime.

We all will.”

Laura Wright

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |