Geotimes

Energy & Resources

Controversial mineral deposit sold

Mineral Resource of the Month: Lead

Controversial mineral

deposit sold

Since it

was first discovered by Exxon in the 1970s, the Crandon copper-zinc deposit in

Wisconsin has been an on-again-off-again venture for mining companies and a source

of apprehension for some local residents. Nestled in forest in the Wolf River

watershed, one of the last pristine rivers in the Midwest, the deposit contains

almost a million metric tons of copper and about 4 million metric tons of zinc,

making it one of the top 20 volcanic-associated metal sulfide deposits in the

world — and the largest in North America. The area also contains sacred sites,

burial sites and wild rice stands in small lakes, harvested by Native American

tribes from nearby reservations.

Since it

was first discovered by Exxon in the 1970s, the Crandon copper-zinc deposit in

Wisconsin has been an on-again-off-again venture for mining companies and a source

of apprehension for some local residents. Nestled in forest in the Wolf River

watershed, one of the last pristine rivers in the Midwest, the deposit contains

almost a million metric tons of copper and about 4 million metric tons of zinc,

making it one of the top 20 volcanic-associated metal sulfide deposits in the

world — and the largest in North America. The area also contains sacred sites,

burial sites and wild rice stands in small lakes, harvested by Native American

tribes from nearby reservations.

The Crandon deposit is set in Wisconsin’s

northern woods. Photo by Tom Fitz.

The deposit’s unique cultural and economic value has stood at the heart of

a decades-long struggle to obtain mine permits. In October, the surprise sale

of the Crandon deposit by Nicolet Minerals Company to two local Native American

tribes ended speculation and plans for mining zinc and copper in northern Wisconsin.

“I feel so grateful because we’ve been able to protect many generations,

and I literally can’t stop feeling good about that,” says Tina Van Zile,

vice chair of one of the tribes and the new president of Nicolet Minerals. “To

know that we will be able to ensure things as clear water and plants and wild

rice … let alone all the burial sites that will be intact.”

The Crandon deposit originated in Proterozoic ocean crust, now incorporated into

the North American craton. The mineral body sits below 125 feet of porous glacial

till. Its setting complicates water and waste disposal issues affecting groundwater

and nearby streams and lakes, concerns that have haunted the Crandon deposit mine

for almost 30 years.

After exploration in the 1960s and 1970s, Exxon started the permitting process

for the first time in the early 1980s. Environmentalists and Native Americans

intensified their protests. In 1986, the company withdrew, as zinc and copper

prices plummeted. When the market for metals strengthened, the company once more

sought a permit to mine in 1994.

In the meantime, the Wisconsin legislature tightened regulations on mining. “By

virtue of our laws and rules, we require an extensive evaluation and more or less

that compliance be proven up front,” says Larry Lynch, mining team leader

for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR). “That’s a tall

order.”

Also, he says, the most recent Crandon project changed hands several times, with

several modifications to mining plans, further complicating and delaying the permitting

process: Rio Algom bought out partner Exxon, and then BHP Billiton, one of the

largest metal mining companies in the world, acquired Rio Algom. Adding further

discord, environmental coalitions questioned the jobs and income the mining companies

promised; industry accused local citizens of knee-jerk environmentalist backlash.

“This was an important resource that needed to be developed,” says Dale

Alberts, a former president of Nicolet Minerals. Had it gone forward, the 30-plus-year

mining operations could have given about a $4-billion boost to “a very poor

county” — Wisconsin’s second poorest — he says.

Two independent

appraisers for the state, which briefly considered buying the land in 2002, judged

the proposed mine site worth about $52 million or $91 million, with mining rights.

However, the ability to use those rights — and the issuance of a permit —

remained uncertain because of lingering concerns over water contamination.

Two independent

appraisers for the state, which briefly considered buying the land in 2002, judged

the proposed mine site worth about $52 million or $91 million, with mining rights.

However, the ability to use those rights — and the issuance of a permit —

remained uncertain because of lingering concerns over water contamination.

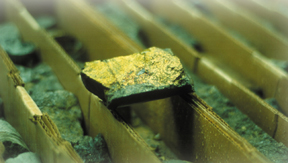

Cores confirmed what magnetic anomalies

indicated was a huge metal sulfide ore body, filled with chalcopyrite (shown here)

and sphalerite. Photo by Tom Fitz.

In addition to Exxon’s initial investments, including permitting costs, drilling

and other exploration, tens of millions of dollars went toward the development

of a mine, with pollution prevention plans in mind. Rio Algom alone invested millions

of dollars into the permit application and in creating a cutting-edge design for

remediation and pollution prevention during the mine’s life. According to

Nicolet Mineral’s most recent plans, the underground mine would be refilled

with a mixture of pyrite tailings and cement in order to isolate any sulfur that

could cause acid drainage on the surface. Other measures, including intense wastewater

treatment and a blanket of grout over the mine, would further control contamination

and water flow. DNR also created innovative and extensive groundwater and contaminant

flow models, Lynch says.

Nicolet Mineral’s own models show, however, that future groundwater effects

might be unavoidable, requiring constant monitoring even hundreds of years after

the mine shuts down. DNR could not allow the project to go forward without the

development of an acceptable plan to avoid such problems.

Such obstacles in the permitting process may have played a role when the Northern

Wisconsin Resource Group, a regional lumber company that is family owned and managed,

bought the land last April for an undisclosed amount. The company intended to

find an experienced mining partner: None stepped forward. Months later, on Oct.

28, the Sokaogon Chippewa Community Mole Lake Band (which earns revenue from gambling

on its reservation) and the Forest County Potawatomi Community bought Nicolet

Minerals and the Crandon land for $16.5 million, including all mineral rights.

Although he hesitates to speculate on the impact of Crandon’s sale on mining

in Wisconsin, Lynch notes that because the state legislature continued to change

regulations — passing a “mining moratorium” act in 1998 —

exploration applications have stopped. Surveys have shown industry perceives Wisconsin

as an unfavorable place to do business. The Crandon project withdrawal probably

will not improve that negative perception, Lynch says.

Van Zile says that for the foreseeable future the tribe does not intend to exercise

the mineral rights. “I can’t say what a new council would do,”

she says. “As far as right now, there’s no technology that’s safe

enough to pull this off.”

Naomi Lubick

Back to top

Mineral

Resource of the Month: Lead

U.S. Geological Survey Lead Commodity Specialist Gerald R. Smith has prepared

the following information on lead — one of the world’s most widely used

and recycled metals.

The United States is a major producer and consumer of refined lead, representing

almost one quarter of total world production and consumption. Two mines in Alaska

and six in Missouri accounted for 97 percent of domestic lead production in

2002. The United States also imports enough refined lead to satisfy almost 20

percent of domestic consumption. Other major producers or consumers of refined

lead in the world are Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan

and the United Kingdom.

Lead is a very corrosion-resistant, dense, ductile and malleable blue-gray metal

that people have used for at least 5,000 years. Ancient Greeks and Romans used

lead for building materials, pigments for glazing ceramics and pipes for transporting

water. The castles and cathedrals of Europe contain considerable quantities

of lead in decorative fixtures, roofs, pipes and windows. And in the United

States, early uses of lead were in ammunition, brass, burial vault liners, ceramic

glazes, leaded glass and crystal, paints, pewter, solders and pipes.

In the 20th century, however, the phenomenal growth of motor vehicle manufacturing

dramatically altered the market profile for lead, as demand grew for its use

in starting-lighting-ignition (SLI) batteries and gasoline additives. Use of

lead in the production of such batteries for motor vehicles accounted for 70

percent of the reported consumption of lead in the United States by 2003. In

addition, lead use increased in batteries for a wide range of vehicles that

are not gasoline-powered, including wheelchairs, golf carts, airport ground-support

equipment, industrial forklifts and mining vehicles.

Other technological advances during the last century further prompted greater

use of lead in batteries for uninterruptible and emergency power in hospitals

and national defense installations, as well as for telecommunications and computer

systems. Lead use in all battery types reached 87 percent of reported consumption

by 2003. The use of lead for radiation shielding in medical devices, video displays

and military hardware also became important new markets for the metal in the

latter part of the 20th century.

Bans on lead — because of health risks to people — essentially eliminated

its use in gasoline and paint additives during the past 30 years in the United

States. The use of lead in SLI automotive-type batteries, however, has continued

to grow steadily. Consequently, domestic recycling of spent lead-acid batteries,

particularly SLI batteries, has also risen in response to environmental concerns

about lead. By 1980, recovery of lead through the recycling of old scrap in

the United States had reached 581,000 metric tons, representing 51 percent of

U.S. refined lead production and 69 percent of all refined lead consumed domestically.

Today, almost 80 percent of U.S. lead production is derived through recycling

under strict environmental standards and satisfies about 80 percent of U.S.

refined lead demand. The lead-acid battery, with a 97-percent recycling rate,

is now the most highly recycled consumer product in the United States.

Of the 1.12 million metric tons of lead recycled in 2003, about 99 percent was

produced by seven companies with 15 plants in 11 states across the country.

Most of the recycled lead was recovered either as soft lead or lead alloys to

be reused in the manufacture of lead-acid storage batteries.

For more information on lead, visit the USGS

minerals Web site.

Back to top

Since it

was first discovered by Exxon in the 1970s, the Crandon copper-zinc deposit in

Wisconsin has been an on-again-off-again venture for mining companies and a source

of apprehension for some local residents. Nestled in forest in the Wolf River

watershed, one of the last pristine rivers in the Midwest, the deposit contains

almost a million metric tons of copper and about 4 million metric tons of zinc,

making it one of the top 20 volcanic-associated metal sulfide deposits in the

world — and the largest in North America. The area also contains sacred sites,

burial sites and wild rice stands in small lakes, harvested by Native American

tribes from nearby reservations.

Since it

was first discovered by Exxon in the 1970s, the Crandon copper-zinc deposit in

Wisconsin has been an on-again-off-again venture for mining companies and a source

of apprehension for some local residents. Nestled in forest in the Wolf River

watershed, one of the last pristine rivers in the Midwest, the deposit contains

almost a million metric tons of copper and about 4 million metric tons of zinc,

making it one of the top 20 volcanic-associated metal sulfide deposits in the

world — and the largest in North America. The area also contains sacred sites,

burial sites and wild rice stands in small lakes, harvested by Native American

tribes from nearby reservations. Two independent

appraisers for the state, which briefly considered buying the land in 2002, judged

the proposed mine site worth about $52 million or $91 million, with mining rights.

However, the ability to use those rights — and the issuance of a permit —

remained uncertain because of lingering concerns over water contamination.

Two independent

appraisers for the state, which briefly considered buying the land in 2002, judged

the proposed mine site worth about $52 million or $91 million, with mining rights.

However, the ability to use those rights — and the issuance of a permit —

remained uncertain because of lingering concerns over water contamination.