In 1898, a Swedish

immigrant farmer was clearing his land in west-central Minnesota, near Kensington,

when he found a tombstone-shaped stone that was covered with unintelligible

carved figures, resembling old Scandinavian runes. Some claim that the rune-covered

stone is a hoax perpetrated by the farmer, while others claim that the rune

stone is the greatest American artifact: If legitimate, it would mean that Scandinavians

reached the interior of North America more than 130 years before Columbus. New

geologic evidence may lend some credibility to that claim.

In 1898, a Swedish

immigrant farmer was clearing his land in west-central Minnesota, near Kensington,

when he found a tombstone-shaped stone that was covered with unintelligible

carved figures, resembling old Scandinavian runes. Some claim that the rune-covered

stone is a hoax perpetrated by the farmer, while others claim that the rune

stone is the greatest American artifact: If legitimate, it would mean that Scandinavians

reached the interior of North America more than 130 years before Columbus. New

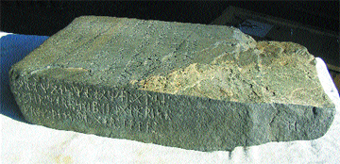

geologic evidence may lend some credibility to that claim.Geologists are trying to determine whether this stone, found in 1898 and covered with ancient Swedish runes telling a tale of a massacre of a band of Scandinavian explorers in Minnesota in 1362, is authentic. Courtesy of Scott Wolter.

Runes are characters from an old Scandinavian alphabet, widely used from the third to the 13th centuries and continuing in lesser usage throughout the next centuries. The Kensington rune stone's inscription, dated 1362, tells of a band of Scandinavians moored near a lake in Minnesota, who returned to camp after a day of fishing to find their comrades massacred, says Richard Nielsen, an engineer and expert on the Kensington rune stone.

When the farmer, Olaf Ohman, found the stone in 1898, many of the words and runes were unknown to linguistics experts, Nielsen says. Furthermore, a fair number of these words are part of the modern Swedish language, which led to suggestions that the farmer carved the inscription. Recent discoveries in Sweden, however, show that all of the words represented by runes on the stone can be found in Old Swedish and were in use in the 1300s, Nielsen says. It is highly unlikely, he says, that a 19th century farmer would know these words were authentic, if linguistics experts did not even know that until recently.

Still, the exact date of the stone has been in question. So in 2000, the Kensington Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minn., asked Scott Wolter, a geologist and president of American Petrographic Services in St. Paul, to perform "an autopsy" on the 202-pound rock to determine when the runes were carved.

A metamorphosed greywacke — a dark-colored, coarse-grained sandstone with abundant mica, quartz, feldspar and rock fragments — the stone is probably at least 1.85 billion years old, says Dick Ojakangas, a geologist at the University of Minnesota in Duluth, who worked with Wolter on the geologic study. Deep glacial striations run roughly parallel down the backside of the stone — the one side that isn't covered in runes — indicating that it was likely plucked from its original bedrock location by glaciers.

For comparison, Wolter sampled inscribed tombstones in Hallowell, Maine, that were subject to similar weathering conditions as the Kensington rune stone. He found that on the surface of the slate tombstones that were older than 200 years, all the biotite mica had weathered out, whereas younger tombstones still had remnant mica grains. Turns out that the carved parts of the Kensington rune stone also showed no signs of mica, Wolter says. Thus, he concluded that the Kensington inscription had to be from the year 1700 or earlier (it has been in museums since it was found, so it hasn't substantially weathered in the past 100 years).

A remaining problem, Wolter recognizes, is that he can only prove that Ohman did not carve the inscription; he has no evidence that it specifically dates to 1362. Still, Wolter believes that the stone is authentic. The facts — the linguistics, historic record and geologic details — "all line up,” he says.

The geologic studies "are certainly interesting and add to the complete picture, but there isn't a lot of proof yet," says William Fitzhugh, curator of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History's arctic collections.

Smithsonian geologist Sorena Sorensen also remains unconvinced. "Resolving ages a few hundred years apart is very difficult," she says. "I don't think the technology is there yet to be able to differentiate 19th century from 14th century artifacts based solely on weathering rates."

Others aren't quite as skeptical: "As a very interested observer, I don't think it has been proven that the rune stone is a fake. Several lines of evidence indicate that it may be authentic," Ojakangas says. But, he adds, more evidence will certainly be needed before its authenticity will be widely accepted.