In

1964, I first became involved with training astronauts in geology for the Apollo

missions. What I found is that teaching geology to astronauts is fun! They are

smart and interesting people, and while most have little or no knowledge of

geology, they all want to learn. The best way to teach geology is in the field,

which is why for the past 40 years, I have been taking these adventurers into

the field, using geological analogs here on Earth, particularly in the western

United States.

In

1964, I first became involved with training astronauts in geology for the Apollo

missions. What I found is that teaching geology to astronauts is fun! They are

smart and interesting people, and while most have little or no knowledge of

geology, they all want to learn. The best way to teach geology is in the field,

which is why for the past 40 years, I have been taking these adventurers into

the field, using geological analogs here on Earth, particularly in the western

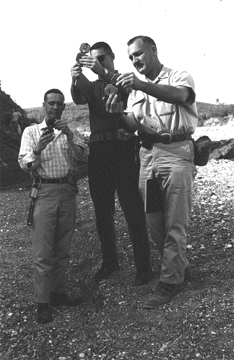

United States. Bill Muehlberger (right) shows Apollo astronauts C.C. Williams (center) and Don Eisele (left) how to use a Brunton compass, while on a field trip in the Marathon fold belt in Texas in the spring of 1964. Courtesy of NASA.

Originally, the Apollo astronauts went to classic field areas with the local experts. For example, their first trip was to the Grand Canyon with Eddie McKee of the U.S. Geological Survey. I helped organize and run their second field trip covering basic field-mapping techniques in the Marathon fold belt in Texas. After these trips, the emphasis was on igneous and impact geology.

The field trips in preparation for moon landings were designed as instruction about the specific landing site. For the Apollo 15 through 17 missions, the "Big Science" missions, field trips took place every other month for the year and a half before launch. We went to places that we thought would show geologic features and problems similar to those they would encounter on the moon, such as impact craters and volcanic areas. Gordon Swann, principal investigator for the geology team for Apollo 14 and 15, worked with the prime crew, and I worked with the backup crew for Apollo 15. When I became principal investigator for Apollo 16 and 17, we switched roles.

Each daily traverse of the two-day field trips was designed to be of similar length to the proposed traverses on the moon. Our only contact with the crew during a traverse was via the "Capcom," an astronaut in Mission Control who would talk to the crew on the moon. We would speak directly to the Capcom, who spoke to the astronauts. After radio debriefing, the local expert took over. He had been with the crew during the traverse, had heard the two-way radio conversation and had seen what the astronauts actually did. He commented at each stop on the effective and ineffective aspects of the conversation or sampling. Because there were always two crews training for a mission, there were always two sets of radios, vehicles and equipment per fieldtrip.

This type of training was key to the success of the Apollo missions. John Young and Charles Duke had been backup crew for Apollo 13, went to the moon on Apollo 16, and were assigned as backup crew for Apollo 17; they had trained for three very different missions to different geologic settings. At the "roast" for my retirement from teaching at the University of Texas at Austin, they proclaimed that they were "the best-qualified lunar field geologists in the world."

Field trips were not a part of the training for either the Skylab missions or the Apollo-Soyuz mission. Time was short and only classroom lectures fit into the schedule. Skylab was the first U.S. space station from which the astronauts made a wide variety of observations and documented them with excellent photos. They also covered the United States with excellent photos, while testing various films before the advent of Landsat.

Sally Ride, a physicist and one of the astronauts waiting to fly on the space shuttle, was assigned the task of determining what scientific research could be conducted from the window of the shuttle. Obviously geology was one subject, with oceanography and meteorology being other major topics. She would fly with another astronaut (different each time) to Austin, and we would spend a day discussing geology and looking at maps, among other activities. Out of those discussions developed a series of lectures (to be given at Johnson Space Center) and a geological field trip to northern New Mexico.

Earth-orbiting missions require a wide knowledge of geology, and all of northern New Mexico could serve as a geologic training ground. Virtually all shuttle and NASA space station astronauts have joined me on a four-day field tripto examine the great and varied geology exposed in this region. In addition to the geological instruction, in 1999 and 2004 (most recently, this past summer), the groups spent another day performing gravity traverses through the town of Taos and vicinity to assist in delineation of buried faults that would affect the distribution of groundwater. Gravity readings had been made on the moon during the Apollo missions to determine the structure of the satellite, and such tests will help in understanding the subsurface geology on Mars.

My part in the geological training of astronauts is small compared to what they receive from the full-time staff at Johnson Space Center. They receive lectures on the various processes that affect Earth, using illustrations taken during earlier Earth-orbiting missions. For a specific shuttle mission, they outline the targets of interest that will be in view from the spacecraft. The space station crew gets daily e-mail updates of transient events (storms, volcanic eruptions, etc.), and they use film cameras as well as digital cameras, images from which are transmitted to Earth for immediate use.

When Dick Truly (shuttle pilot for the second Apollo mission, commander of the eighth, and later NASA administrator from 1986 to 1992) was on campus at the University of Texas at Austin to give a public lecture, I invited him to visit my senior students, who were laying out poster sessions using sequences of shuttle pictures. One sequence across Algeria showed a major sand dune field. I said, "Dick, are those dunes really that red?" He replied, "I remember them as being redder." This startled the students as I had not introduced him to the class. I pointed out that he had taken them. Twenty years later, when I meet one of those students, they still comment on that day. It is a powerful reminder of the important role these early astronauts played in shaping our view of the planet.