David M. Delo died

on Oct. 31, in Seminole, Fla., of congestive heart failure, two months shy of

his 99th birthday. A medley of plaques, honorary degrees (five of them) and

testimonials reflect what my father once referred to as a "misspent life."

David M. Delo died

on Oct. 31, in Seminole, Fla., of congestive heart failure, two months shy of

his 99th birthday. A medley of plaques, honorary degrees (five of them) and

testimonials reflect what my father once referred to as a "misspent life."

By the time he was 40 years old, my father had abandoned the joys of field geology — but he never forgot the Tertiary turtle he found in the Black Hills, nor did he forget the cold floors of the little mountain cabin at the geology field camp in the Wind River Mountains.

David M. Delo, a geologist shown here circa 1935 outside of an old cabin he stayed in when at the Wind River Geology Field Camp, died on Oct. 31. Courtesy of David Delo Jr.

He was a geologist first, graduating from Miami University of Ohio in 1926 and earning a master's degree from the University of Kansas in 1928 and a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1935. He was a founder and later president of the National Association of Geology Teachers and the first executive director of the American Geological Institute (which publishes Geotimes).

After teaching in several Midwest colleges and universities and holding administrative positions in Washington, D.C., during and after World War II, my father also turned his back on his talent and love of teaching. But he never forgot to tell the story — for decades — about the day he admonished his disbelieving students on a beautiful day that it would storm before noon, and thunder preceded the bell by seconds.

Instead, my father gave in to an obdurate inner voice, and in 1952, he accepted his first college presidency at Wagner College, on Staten Island, N.Y. Six years later, he took over the presidency of the University of Tampa. For the ensuing 16 years, he confronted the challenges that all private educational institutions face — the need to forge an educational philosophy that reaches for excellence and the future, and the urgent need to secure a "golden fleece" to end the plague of inadequate financial support.

"An institution, to be great," my father said, "must maintain great expectations of itself. It must have clear-cut objectives and goals . . . the ability to be flexible and courage to experiment . . . and it must possess an atmosphere which motivates and stimulates the educational process." Those words reflected the expectations that my father held for himself.

One prominent memory stands out in my mind as his son. It was a late summer afternoon, 15 years ago, and he and I stood on a 10,000-foot-high promontory in Wyoming's snowy mountains, sharing a moment of mutual love of nature. Without thinking, he caressed the handle of his geology hammer and spoke to me as though I were one of his students. And even though I was educated as a geologist, I knew that he had forgotten more about Earth than I will ever know.

Halfway down the hill that day he paused and leaned back against a rock. "Aw, hell," he said. "My knees are shot." So that year, at age 82, he cut back. He only attended one archeological dig after his jaunt to Hawaii to peer into Mauna Loa.

I would call my father's life "the life of Dr. David M. Delo: Zen and the art of a life fulfilled."

David Delo Jr.

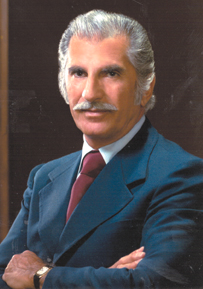

Editors'

note: Michel T. Halbouty passed away on Nov. 6 at the age of 95. After he

received the American Geological Institute’s Legendary Geoscientist Award

in 2001, Geotimes profiled him. The following is modified from that

Editors'

note: Michel T. Halbouty passed away on Nov. 6 at the age of 95. After he

received the American Geological Institute’s Legendary Geoscientist Award

in 2001, Geotimes profiled him. The following is modified from that