Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers

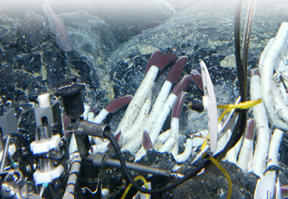

On this return trip,

the researchers wanted to learn how the original Galápagos vent fields

and their fauna had changed. To their surprise, the most famous and best-studied

vent field in the region, Rose Garden, is now gone. The scientists suspect lava

flows paved over the field. Nearby, a young vent community is claiming residency

with small clams and mussels as well as one-inch long tubeworms growing on larger

tubeworms. Disappointed over the loss of Rose Garden, but hopeful that the young

vent field will develop as a community, the scientists named the new site Rosebud.

On this return trip,

the researchers wanted to learn how the original Galápagos vent fields

and their fauna had changed. To their surprise, the most famous and best-studied

vent field in the region, Rose Garden, is now gone. The scientists suspect lava

flows paved over the field. Nearby, a young vent community is claiming residency

with small clams and mussels as well as one-inch long tubeworms growing on larger

tubeworms. Disappointed over the loss of Rose Garden, but hopeful that the young

vent field will develop as a community, the scientists named the new site Rosebud. |

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |