Stevenson’s

paper in the May 15 Nature has captured the attention of both the public

and the earth science community, harkening back to the days of Jules Verne’s

A Journey to the Center of the Earth. But, Stevenson, a planetary scientist

at Caltech, hopes his idea can bridge the gap between the science fiction world

and the research world, encouraging geophysicists to dream big.

Stevenson’s

paper in the May 15 Nature has captured the attention of both the public

and the earth science community, harkening back to the days of Jules Verne’s

A Journey to the Center of the Earth. But, Stevenson, a planetary scientist

at Caltech, hopes his idea can bridge the gap between the science fiction world

and the research world, encouraging geophysicists to dream big.“When I wrote the paper, it was in part a deliberate attempt to shake people up, and it will probably succeed at that independent of whether people finally decide that it’s actually an idea that can be carried out,” he says.

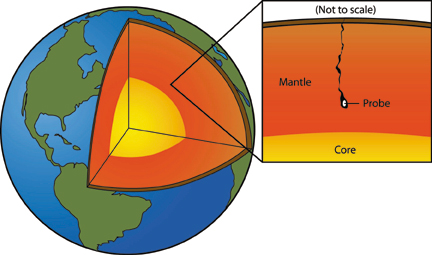

Dave Stevenson, a planetary geologist at Caltech, has proposed sending a grapefruit-sized probe embedded in molten iron down to the Earth’s core to measure ambient conditions and rock composition. Based on principles of magma fracturing, the week-long trip would require an initial 300-meter propagating crack from the surface.

The mission, should geologists choose to accept it, is this: Create a kilometer-deep crack with a force equivalent to a magnitude-7.0 earthquake (also equivalent to a few-megaton TNT explosion or the detonation of a nuclear device within current stockpiled range). Into this crack, pour 100 million tons of molten iron carrying a small probe equipped to sample the planet’s deep. The probe, with diamond as its semiconductor material, would take about a week to reach the core and then communicate fundamental ambient conditions and rock properties via encoded seismic waves back to the surface.

While based on basic equations of volcanism, the proposal boldly challenges current technological limitations, says Jerry Schubert, a geophysicist at UCLA. “The principles on which it’s based are well founded; I couldn’t find any holes in the science. If there are questions about his proposal, I think they’re ones of practicality rather than being scientifically unsound.”

Indeed, the same equations Stevenson cites are those developed over the last couple of decades to explain how magma from Earth’s interior makes its way up to the surface through volcanism — magma, which is lighter than its surrounding rock, rises through natural fractures in Earth. “Stevenson sort of reverses the process and lets some heavier material sink, but it’s the identical concept; the equations are identical,” Schubert explains.

But gathering together such a large quantity of iron, succeeding in propagating a crack through the crust, making sure the iron doesn’t freeze on its way down and instrumenting the probe so that it can actually measure something useful — to name a few — will all prove difficult, he says. And Stevenson agrees. “I actually think that the likelihood of really doing it is quite low,” he says. In fact, very little of the technology necessary to carry out such a feat actually exists, much like the Manhattan Project in 1940, when the technology did not yet exist in order for the atomic bomb to work, he says.

But, the plan’s technical feasibility is not really the point. And many are missing it, Stevenson is quick to add. “The main problem with the media on this story has been a lack of subtlety. Both the journalists and the general public don’t understand the notion that a scientist could be doing something that is partly a joke and partly serious,” he says. Reports of Stevenson’s idea have appeared in newspapers internationally with interviews on everything from National Public Radio and PBS to a morning radio talk show in Seattle.

Upon first glance, the “joke” part does seem hard to find, but Stevenson explains that he attempted to make a serious point without emphasizing the details; only the big picture matters. As a planetary scientist, Stevenson has seen bold ideas proposed for space exploration — such as rovers on Mars and nuclear-powered spacecraft to Europa. With ample financial resources and scientific efforts, the field of space sciences has been able to pursue these big dreams; but no such resources exist for deep Earth, he says. “There is actually an imbalance in the way people devote their mental energy as well as their time and financial resources because of the structure of funding science.”

If Stevenson’s main aim was to get the geological community to listen and to think outside the box, he seems to be succeeding so far. In talking with top geophysicists across the country, words like “provocative,” “intriguing, “exciting” and “challenging” come up. At a June workshop of the Cooperative Institute for Deep Earth Research, Stevenson discussed his idea in the halls and over beer; but, he says, most of the discussions were about his experiences with the media and not the technical feasibility. His proposal is like no other thought of for exploring the core. It may take time for it to develop into more than just a seed in the back of peoples’ minds, he says.

It’s certainly gotten Bruce Buffett, a geophysicist at the University of British Columbia, thinking. “I am part of the conventional crowd that just thinks, well we have seismology and electromagnetic methods; we’re just preconditioned to think this way. So the notion of sending something down there at first seemed absurd when I read the article but then I started wondering if something like this could actually work,” Buffett says.

Geophysicists use seismic waves to infer temperature, pressure and rock densities in the deep interior of Earth; electromagnetic methods and modeling give them clues about the planet’s magnetic and gravity fields. But, Schubert says, “given all that, our information is somewhat difficult to interpret, because we don’t know exactly what’s down there in terms of composition of the rocks, in terms of their properties.”

Knowing those properties, Stevenson says, is key to understanding how Earth formed and evolved. Like exploring other planets, actually going to the core is indispensable to studying it. While working on how to get there, scientists may learn even more about Earth’s structure, says Gary Glatzmaier of the University of California, Santa Cruz. “His idea is to probe the core, but in the process we may learn a lot about the mantle,” he says.

Stevenson also thinks that all this attention surrounding Earth’s core and his proposal may be increasing the public’s understanding of the planet. Before now, people have only associated cracks with earthquake events, not realizing that fractures are part of many Earth processes, such as volcanism. “I think in a small way it may have had a small benefit because it may be that some people will catch onto this idea that cracks are something the Earth does naturally.”

Lisa M. Pinsker