This year’s

hurricane season is promising strong activity due to a confluence in time of

La Niña, which is expected to arrive this summer, with a multidecadal

pattern of tropical rainfall that supports hurricane activity. The hurricane

season officially began June 1, but the time to watch out for the greatest activity

is between mid-August and mid-October, says atmospheric scientist William Gray

of Colorado State University.

This year’s

hurricane season is promising strong activity due to a confluence in time of

La Niña, which is expected to arrive this summer, with a multidecadal

pattern of tropical rainfall that supports hurricane activity. The hurricane

season officially began June 1, but the time to watch out for the greatest activity

is between mid-August and mid-October, says atmospheric scientist William Gray

of Colorado State University. On May 30, Gray and colleagues made available on the Internet their newest estimates for 2003. This season, they say, will have about eight hurricanes (average is 5.9), 14 named storms (average is 9.6), and three intense hurricanes (average is 2.3) that will reach category 3, 4 or 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, where 5 is the highest. In addition, the team reports that estimates that the probability of U.S. major hurricane landfall is about 30 percent above the long-period average.

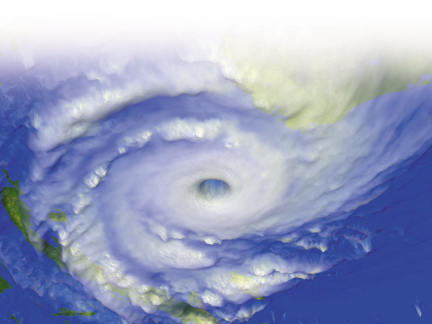

An image of Hurricane Mitch taken from the GOES-8 satellite on Oct. 26, 1998. Hurricane Mitch developed during a La Niña year. Dennis Chesters (NASA/GSFC); taken from NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio Web site.

For the past few years the presence of El Niño has suppressed hurricane activity in the Atlantic, Gray says. But as El Niño petered out in March and April, signs of cooling in the Pacific Ocean in May indicated La Niña was close on its heels.

The stepping in of La Niña at the beginning of the hurricane season is a situation that has only arisen twice in the last eight hurricane seasons, Gray adds. Both 1998 and 1999 had moderate to strong La Niña episodes during the months between July and December, according to NOAA. Hurricane Mitch, for example, was one of the strongest storms ever recorded in the Atlantic and first began as a tropical depression on Oct. 22, 1998, according to the National Climatic Data Center.

La Niña’s typically cooler-than-normal temperatures in the Pacific Ocean influence the global atmospheric conditions and make for an active Atlantic hurricane season. In El Niño or neutral years, wind directions and speeds create a high vertical wind shear between the lower and upper atmospheres, such that the weaker westerly jet stream winds cut off the tops of storms that develop in the strong easterly trade winds. When La Niña enters the scene, it tends to strengthen the upper-level winds and cause the lower trades to lose their gusto. “La Niña tends to make winds more uniform as you go up through the atmosphere,” says senior research scientist Gerry Bell of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. “La Niña contributes to more hurricane activity primarily by acting to decrease the vertical wind shear in the heart of the main development region.”

When predicting hurricane activity, Gray’s team relies on past climatic conditions based on the premise that the ocean and atmosphere will continue to behave in the future as they have in the past. They stress that many atmosphere-ocean circulation and energy-exchange processes are complicated and poorly understood. So-called hindcast studies allow them to forecast based on empirical associations without understanding all the physical processes involved.

Bell agrees that much is still unknown about hurricane forecasting, but says the technology for understanding the interaction of climate and ocean and how it works together has become state of the art since 1998. “And we’re learning more as we go.”

This year, the global oceanic and atmospheric conditions seen between February and May are most similar to five other recorded years: 1952, 1954, 1964, 1966 and 1998. Gray’s team used the mean average of those five analog years to make the 2003 forecast. As the season progresses, the team will continue to analyze the conditions seen and compare them to the hurricane season and pre-season conditions recorded since 1949. “Always when you are closer to the season, you do a little better with the forecast,” Gray says.

Gray’s team gave an extended range forecast for the season in April, anticipating the then weakening El Niño would dissipate by summer. AccuWeather.com forecasts on May 15 gave a 30 to 90 day outlook indicating that the conditions that typically follow El Niño would go on to develop into La Niña during the summer. On May 19, NOAA announced a similar forecast based on cool temperatures recorded in the Pacific indicating a return of La Niña.

Christina Reed