In an effort

to meet growing demands for natural gas in South Florida, two companies are

planning to build underwater pipelines to transport natural gas from the Bahamas

to the region. The planned construction would drill underneath the coral reefs

that lie between the islands and the state. Although scientists and conservationists

have expressed concerns about the impact of the pipelines on the reef system,

the Florida Cabinet voted to approve both projects in April.

In an effort

to meet growing demands for natural gas in South Florida, two companies are

planning to build underwater pipelines to transport natural gas from the Bahamas

to the region. The planned construction would drill underneath the coral reefs

that lie between the islands and the state. Although scientists and conservationists

have expressed concerns about the impact of the pipelines on the reef system,

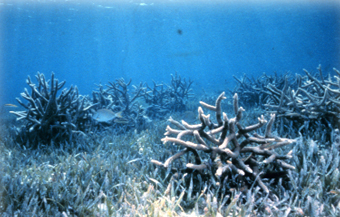

the Florida Cabinet voted to approve both projects in April.Staghorn coral live in seagrass in the Florida Keys Marine National Sanctuary. Two companies are planning to construct underwater pipelines carrying natural gas through a stretch of coral reef north of the sanctuary and down to the Bahamas. Courtesy of the Florida Keys Marine National Sanctuary.

There is little debate that Florida’s fragile coral reefs, like most around the world, are in peril — rising sea-surface temperatures, pollution, overfishing, and damage from divers and boaters all threaten the most extensive living coral reef system in North America. The contested stretch is north of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and is known as the southeast Florida reef tract. It consists of three reef lines that grew between 3,000 and 9,000 years ago. The coral cover on these reefs averages only 2 to 6 percent — compared to recent estimates of 15 to 20 percent in the reefs of the Florida Keys. Although no longer actively growing, they are still home to a rich flora and fauna, including one type of coral, Acropora cervicornis, which is currently under consideration for the endangered species list.

“These reefs are pretty and valuable,” says Bernhard Riegl, associate professor at Nova Southeastern University, “but because they are at the northern end of their range, they are not as lush and diverse as the reefs of the lower Keys and Caribbean.” And conservationists and federal and state officials disagree over whether the pipelines will pose significant danger to these reefs.

Nonetheless, after more than two years of review by an interagency panel that included federal, state and county officials, AES Ocean Express LLC and Tractebel Calypso are each close to getting the green light for pipeline construction underneath the reef. Both projects have already received final approvals from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission; with the state cabinet’s approval, Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) will issue its own permit. “The permitting process follows the mantra: ‘avoid, minimize, mitigate,’” says Jayne Bergstrom, permitting manager of FDEP’s Southeast District.

The pipeline companies will use horizontal directional drilling under the reefs on the Florida side; farther offshore, the pipelines will rest directly on the seafloor. The federal environmental impact statement reports that damage to the reefs during pipeline construction would be minimal.

“We were very tough — we were not easy at all,” Bergstrom says. “There are no clear-cut coral reef protection statutes in the state of Florida; there’s nothing that says ‘thou shalt not touch coral.’” To protect the corals, she says, the state built in extra conditions to the permitting process, including doubling the cost of mitigation for impacts covered in the permits and requiring an additional $5 million bond in case of accidental impacts to the reef. The state also lowered its turbidity threshold for the projects, to reduce stress on the corals.

Still, environmentalist groups worry about the effects of the construction on the reef. Dangers to the reef include “frac-outs” (where bentonite mud used to lubricate the drill is released during drilling) and failed pullback of the pipeline into the drill hole. Mechanical damage is also a major concern, says Dan Clark, president of Cry of the Water, a reef activist group. “Inadvertent anchor damage, vessels dragging lines — if you work around fragile coral reefs, these things are going to happen,” he says. Additional damage could result from the methods proposed by each company to bring in the pipeline once the holes are drilled.

“If they’re going to have a gas pipeline, the thing to do is to have it be environmentally safe,” says Ray McAllister, a professor emeritus of ocean engineering at Florida Atlantic University. McAllister and Clark both say that they would like to see more protection measures in place, including requiring a nearshore shutoff valve in case of gas leaks and using natural gaps in the farthest offshore reef to bring in the pipelines for construction, rather than floating or dragging them in.

Final approval of both projects is still pending from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bahamian government. Nonetheless, both projects will likely obtain approval, with pipeline construction beginning by the end of this year. “The permitting process is pretty stringent,” Riegl says. “How worried you are depends on how much you believe in it.”