Geophenomena

Underwater asphalt living

In 1971, petroleum

geologists in the southern Gulf of Mexico took a bizarre photograph near the

Campeche Knolls oilfield, a region where the evaporite deposits below the seafloor

have warped up into domes. The photo seemingly showed a small patch of asphalt

covering the seafloor. Such an exposure, however, would mean that hot tar was

erupting in the deep, cold Gulf, far from any spreading center or ridge —

a scenario unheard of at the time.

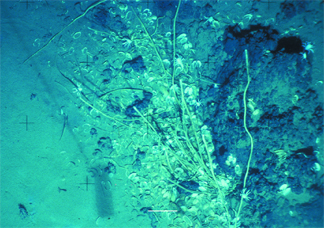

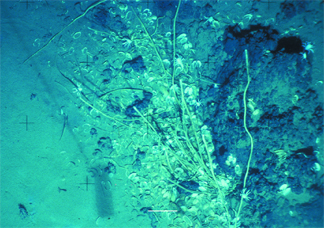

At the edges of the flow field at Chapopote

in the southern Gulf of Mexico, small clusters of tubeworms grow under eroded

asphalt deposits, along with living bivalve shells and galatheid crabs. Photos by Ian

MacDonald, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi.

In November 2003, Ian MacDonald of Texas A&M University and colleagues rediscovered

the site and found something even stranger — an entirely new type of ecosystem.

Three thousand meters below the Gulf’s surface, where no sunlight penetrates

and bottom waters are a chilly 4 degrees Celsius, abundant tubeworms, large

bivalves and crabs were colonizing an asphalt flow. Successive flows appeared

to have covered previous ones and in some cases, flowed over tubeworms, embedding

them in the asphalt.

“There’s nothing really comparable to this system anywhere in the

world,” says Samantha Joye, a University of Georgia biogeochemist. While

Joye has worked on other chemosynthetic communities in the Gulf, she says that

the site at Campeche Knolls is unique from the previously discovered systems,

which are located at shallower hydrocarbon seeps that provide abundant food

sources for microorganisms.

The Campeche

Knolls site — named Chapopote, the Aztec word for tar — is a salt

dome with approximately 1 square kilometer of a lava-like flow of solidified

asphalt around its rim, as described by MacDonald’s team in the May 14

Science. Radial fracturing and columnar jointing of the asphalt flow

suggest rapid cooling.

Katja Heeschen of the Research Center for Ocean Margins at the University of

Bremen in Germany holds a piece of carbonate, which was collected from the Chapopote

site and is covered in crude oil and sediment.

The association between the asphalt and the fauna is unclear and especially

surprising, Joye says, because asphalt is not a very good food source. “Asphalt

is the last thing you get when you are thermally altering carbon, so it’s

not very nutritious,” Joye says. “The fact that you’ve got anything

growing on this asphalt at all, I find astounding.”

Researchers found most of the fauna located on the edges of the asphalt flow

and in cracks on the surface. This location and the fact that other Gulf tubeworms,

unlike hydrothermal vent tubeworms, use root-like structures to absorb sulfide

from the sediments suggest that the asphalt organisms are subsisting on something

migrating from below, Joye says. The specific chemosynthetic pathways used by

the asphalt communities to gain energy, however, remain unknown.

The team found Chapopote using satellite imagery to first identify oil slicks

on the surface of the southern Gulf and then, after accounting for ocean currents,

modeled the probable deep provenance of the slicks. Given that large areas of

the Gulf floor are similar to Campeche Knolls, the authors say that such asphalt

volcanism and the chemosynthetic communities that inhabit them may be widespread.

If so, satellite surveillance will play an important role in discovering them.

William Schroeder, an oceanographer at the University of Alabama Dauphin Island

Sea Lab and editor of the journal

Gulf of Mexico Science, says that the

Chapopote discovery has opened up a myriad of research opportunities. “We

hear the clichés so often lately that we know more about Mars and the

Moon than we do about the deep sea. This paper shows there are still significant

discoveries to be made here in our very own backyard,” he says.

Sara Pratt

Geotimes contributing writer

Back to top

In 1971, petroleum

geologists in the southern Gulf of Mexico took a bizarre photograph near the

Campeche Knolls oilfield, a region where the evaporite deposits below the seafloor

have warped up into domes. The photo seemingly showed a small patch of asphalt

covering the seafloor. Such an exposure, however, would mean that hot tar was

erupting in the deep, cold Gulf, far from any spreading center or ridge —

a scenario unheard of at the time.

In 1971, petroleum

geologists in the southern Gulf of Mexico took a bizarre photograph near the

Campeche Knolls oilfield, a region where the evaporite deposits below the seafloor

have warped up into domes. The photo seemingly showed a small patch of asphalt

covering the seafloor. Such an exposure, however, would mean that hot tar was

erupting in the deep, cold Gulf, far from any spreading center or ridge —

a scenario unheard of at the time.  The Campeche

Knolls site — named Chapopote, the Aztec word for tar — is a salt

dome with approximately 1 square kilometer of a lava-like flow of solidified

asphalt around its rim, as described by MacDonald’s team in the May 14

Science. Radial fracturing and columnar jointing of the asphalt flow

suggest rapid cooling.

The Campeche

Knolls site — named Chapopote, the Aztec word for tar — is a salt

dome with approximately 1 square kilometer of a lava-like flow of solidified

asphalt around its rim, as described by MacDonald’s team in the May 14

Science. Radial fracturing and columnar jointing of the asphalt flow

suggest rapid cooling.