As

the Deep Impact spacecraft nears its intended target, comet Tempel 1, this month,

people around the world are climbing atop their roofs equipped with high- and

low-tech telescopes to see if they, too, can witness the comet collision. What

they observe or, better yet, capture on film both during the event and in the

weeks before and after, could prove useful to the team of NASA scientists trying

to understand the comet and the effects of the impact (see related

story).

As

the Deep Impact spacecraft nears its intended target, comet Tempel 1, this month,

people around the world are climbing atop their roofs equipped with high- and

low-tech telescopes to see if they, too, can witness the comet collision. What

they observe or, better yet, capture on film both during the event and in the

weeks before and after, could prove useful to the team of NASA scientists trying

to understand the comet and the effects of the impact (see related

story). University of Maryland sophomores Brad Poston and Rob Cullen try to capture images of comet Tempel 1 from the university’s observatory in College Park, Md. NASA has asked amateurs around the world to photograph the comet before, during and after its collision with the Deep Impact spacecraft.

As the world becomes more interconnected by the Internet, members of the public are increasingly helping scientists with their research — through personal observations of everything from birds and weather to the stars, as well as by allowing scientists use of their home computers for projects ranging from searching for extraterrestrial life (SETI@Home) and gravity waves (Einstein@Home), to predicting the changing global climate (climateprediction.net; see Geotimes Web Extra, Feb. 7, 2005). These new partnerships not only help the scientists, but also keep the public interested and involved in current scientific research.

NASA has long involved amateurs in the observation process for its missions, says Elizabeth Warner of the University of Maryland, and has designed two programs related to Deep Impact: the Small Telescope Science Program and the Amateur Observers Program. NASA formed the two programs to “get people involved,” Warner says. “Telling people to go to the nearest observatory doesn’t fly — they want to do it themselves, which we encourage.”

The Amateur Observers program is designed to involve anyone who wants to observe the comet collision and submit their observations, whether a photograph, sketch or text description, Warner says. The Small Telescope Science Program is more aimed at technically proficient amateurs who can collect scientific data with their telescopes and charge-coupled-device (CCD) cameras. Both programs, but especially the small telescopes program, are designed to complement data collected by large telescopes, Warner says.

Comet Tempel 1 is “not very bright or easy to see, so it takes a good telescope and a good CCD camera,” Warner says. The small telescopes program focuses on continuous monitoring of the comet before, during and after impact, looking for changes in the brightness of the dust-covered head of the comet and tail, and changes in behavior or movement, she says.

Large observatory telescopes only capture the comet once a month on average, so the hope is that amateurs can fill in any gaps that the observatories miss, Warner says. “Amateurs can go out every night if they want and get good time-lapse photos,” she says. “They can really help the scientific process.”

To participate, people log on to either program’s Web site, create a profile that includes the type of equipment they used, their location and weather conditions at the time of the observation, and then upload photos or fill in observations.

In a similar program, through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Citizen Science program, birdwatchers around the world help scientists collect data to learn about birds. Simple projects allow amateurs anywhere to participate, for example, by counting nests or observing migration and mating patterns.

People sign on to the lab’s Web site and pick a project with which they would like to help, based on where they live and how much time they want to spend. There are year-round projects, such as studying what types of birds live in urban environments, as well as seasonal projects, such as the Great Backyard Bird Count, where people count all the birds that visit their backyards over four days in the winter. This year, more than 51,000 checklists were submitted, including observations of more than 6.5 million individual birds and 613 different species.

Whatever project people choose, they receive a detailed set of instructions along with a list of further resources. Like the Amateurs Observers Program for Deep Impact, the Cornell Citizen Science program is designed so that anyone of any age, experience or education level can participate and help scientists with research.

The

Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow network, based

at Colorado State University, is also designed for anyone. Many of the participants

are retired professionals, but the ages vary widely, with the youngest only

five years old, says Nolan Doesken, a climatologist at Colorado State who created

and runs the program. “Citizen volunteers have a long history in weather

and climate studies,” he says, dating back to before the Civil War. Since

the 1880s, climatologists and meteorologists have utilized citizens to monitor

day-by-day weather as well as long-term climate patterns and variations. And

today, most television stations have local “weather-watchers” that

they rely on to report what is happening, he says.

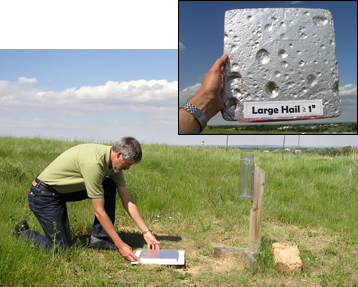

The

Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow network, based

at Colorado State University, is also designed for anyone. Many of the participants

are retired professionals, but the ages vary widely, with the youngest only

five years old, says Nolan Doesken, a climatologist at Colorado State who created

and runs the program. “Citizen volunteers have a long history in weather

and climate studies,” he says, dating back to before the Civil War. Since

the 1880s, climatologists and meteorologists have utilized citizens to monitor

day-by-day weather as well as long-term climate patterns and variations. And

today, most television stations have local “weather-watchers” that

they rely on to report what is happening, he says. Climatologist Nolan Doesken places a Styrofoam hail pad, covered with aluminum foil and measuring 1 square foot, near a rain gauge in Colorado. The instruments measure the size of hail and the amount of rain or snow, as part of a six-state public participation program to track weather and climate. Inset: This damaged hail pad shows hail ranging from pea-sized to greater than 1 inch in diameter. Images courtesy of Henry Reges.

But for the weather in Colorado, meteorologists needed to design a more sophisticated observations program. Most major thunderstorms include hail, which causes millions of dollars in damages each year. The severe weather is so localized, however, that existing weather stations don’t pick up on it, Doesken says.

So in 1997, Doesken and a pair of high-school volunteers set out to see if using low-cost measuring instruments could better track where hail was hitting. In the middle of their testing, a “highly localized” flash flood occurred at the university, Doesken says. With the help of hundreds of volunteers, they were able to piece together what happened. Suddenly, their little pilot project took off, he says.

In just over five years, more than 2,000 volunteers have participated throughout Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Kansas, Nebraska and Texas. In 2004, they logged 18,000 hours of volunteer time. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service has also begun using the citizens’ data, Doesken says.

Getting involved is easy, Doesken says, and staying involved does not take a lot of time. People sign up on the Web site and receive a station identification number and a supply kit. Supplies cost about $40 per station, which participants are asked to pay if they can, he says, but no one has to pay to participate, as several sponsors help cover volunteer costs.

The equipment includes a 4-inch-diameter rain and snow gauge that measures to the nearest 1/100th of an inch, a mounting bracket, and a bag “with lots of brand-new hail pads,” Doesken says. The hail pads are 1 square foot of Styrofoam wrapped with heavy-duty aluminum foil, shiny side down (to prevent excess bird attraction). People mount the rain gauges and hail pads in their backyards, and then check them every morning to record any precipitation that fell. They then empty the rain gauges and bring in damaged hail pads.

Doesken says that working with the public is both rewarding and challenging. “You have to be a people-person and a fast typist to enjoy the consequences of this project,” he says. “We get a ton of wonderful scientific data every day, but also an e-mail box full of questions and correspondences from our volunteers.” But, he says, by “engaging the people and stimulating their thoughts, they get even more engaged — it’s public education as well as scientific research.”

Indeed, public observation projects allow people to take a more active role in scientific research, says Bruce Allen of the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Allen leads Einstein@Home, a computing project that uses idle time on participants’ computers to look for gravity waves by searching for spinning neutron stars (called pulsars), the finding of which could prove the last remaining prediction of Einstein’s theory of gravity.

“These projects allow people to discover science and work on it themselves instead of just reading about it,” Allen says. “And if we discover something, they would have played a very active role in it. It’s exciting.”

Megan Sever

Links:

"Collision Course: Deep Impact," Geotimes, July 2005

SETI@Home

Einstein@Home

ClimatePrediction.net

"Virtual climate experiment's results," Geotimes Web Extra, Feb. 7, 2005

Small Telescope Science Program (Deep Impact)

Amateur Observers Program (Deep Impact)

Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Citizen Science program

Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network