The ancestors

of birds are widely believed to be dinosaurs, but the specifics of bird origin

are still unclear. Now, geologists have found footprints in northwest Argentina

that are evidence for the oldest bird-like creatures discovered.

The ancestors

of birds are widely believed to be dinosaurs, but the specifics of bird origin

are still unclear. Now, geologists have found footprints in northwest Argentina

that are evidence for the oldest bird-like creatures discovered.

The ancestors

of birds are widely believed to be dinosaurs, but the specifics of bird origin

are still unclear. Now, geologists have found footprints in northwest Argentina

that are evidence for the oldest bird-like creatures discovered.

The ancestors

of birds are widely believed to be dinosaurs, but the specifics of bird origin

are still unclear. Now, geologists have found footprints in northwest Argentina

that are evidence for the oldest bird-like creatures discovered.

"This finding poses many questions regarding the origin of birds and the relationships of this unknown group of theropod dinosaurs with other groups of dinosaurs," says Ricardo Melchor from the Universidad Nacional de La Pampa in Argentina, and lead author of the group that published its findings in this week's Nature. "It's significant because we find footprints with morphology identical to modern birds in rocks that predate, by 55 million years, the first record of true Aves."

Ricardo Melchor in his laboratory working on categorizing the oldest bird-like footprints discovered. These footprints predate, by 55 million years, the oldest bird body fossils known. Photo supplied courtesy of Ricardo Melchor.

These footprints are older than the oldest bird body fossils, those of the Archaeopteryx, a feathered cross between dinosaur and bird, that existed in the late Jurassic (150 million years ago). Prior to this, coelurosaurs, recognized as ancestors to birds, have been known to exist as far back as the early Jurassic. Earlier references have been made to bird-like footprints found in the late Triassic and early Jurassic, but they are controversial. To date the tracks to the late Triassic, Melchor and his team used radiometric dating, lithologic comparison, and identification of a late to middle Triassic wood fossil in the same unit of rock.

Criteria such as width to length ratios of the prints, size of the digits (slender vs. thick), angles between the digits and the absence or presence of a distinct pad impression helped characterize the footprints. These are all telltale signs of animal behavior. For example, a horse's prints will look very different from a tiger's prints and point to different evolutionary adaptations.

"These footprints are really something unique," Martin Lockley, paleontologist from the University of Colorado-Denver, says. "It proves that tracks can provide us with surprising information. Tracks are often easier to find than bones and track evidence has been the precursor of important discoveries."

"The first and most striking feature of these fossil footprints is the overall resemblance with modern bird footprints," Melchor says. In many birds, the hallux marks the innermost toe. In human beings this would correspond to the big toe, but unlike in human beings or other non-avian animals, the hallux points backwards in birds. One of the advantages of the evolution of this digit is that it makes it possible for birds to perch. The imprint of the hallux in the late Triassic tracks is a distinct bird-like feature, Melchor explains.

Other features such as slender digits and claws and wide angles between the second and fourth digits also point to bird-like morphology. In addition, the fact that the footprint tracks lack a preferred orientation and occur in shallow lake environment sediments suggests the typical activity of water birds along present day lakes.

Melchor and

team indicate that there are some features that do not correspond to bird morphology,

but these are few. One example is the presence of pad impressions in some of

the footprints. Other features that might be bird-like, but could be common

to other theropods include the wide angles between the second and fourth digits.

Melchor and

team indicate that there are some features that do not correspond to bird morphology,

but these are few. One example is the presence of pad impressions in some of

the footprints. Other features that might be bird-like, but could be common

to other theropods include the wide angles between the second and fourth digits.

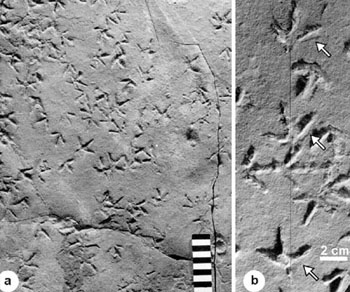

a) Footprints are numerous in this slab

of the Santa Domingo Formation.

b) The arrows point to a track of footprints. Visible in each print of the track

is the hallux, the digit that points backwards in birds. Photo supplied courtesy

of Ricardo Melchor.

Because of these morphological inconsistencies, Melchor and his team are cautious in claiming that they have found evidence of birds or ancestors to birds. "We have a spot in the late Triassic that uncovers the unexpected existence of these animals. There are some debatable findings of footprints in the early Jurassic and late Triassic, true birds and bird-like dinosaurs occur in the late Jurassic, but there is an immense time lapse in between where nothing is known," Melchor says.

Other paleontologists, such as Lockley agree, "The evidence is interesting and these do look like bird tracks, but at the moment we can't know if they are true birds. It's important, however, not to dismiss the track evidence as invalid until the skeletons are found."

Other late Triassic age bird-like footprints have been recorded in southern Africa, but the research has been questioned and its clarity debated. "In my opinion, the footprints in Argentina seem similar to those from southern Africa. However, what is commendable here is that the Argentineans have presented their material well and these footprints seem to be distinctly bird-like and different from any known dinosaurs walking around at the time," Lockley says.

Further research that unearths other fossil remains could generate decisive

answers about bird origins. For the time being, as Melchor states, "the

hope is that this finding will motivate a lot of research and discussion."

Salma Monani

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |