Geotimes

Feature

Geology for the

Record

Marjorie A. Chan, Donald R. Currey,

Andrea N. Dion and Holly S. Godsey

Visit Geotimes.org

later this month for stories on geoconservation in the UK and Europe.

Just outside the town of Stockton, a bedroom community of Salt Lake City, is a

unique geological feature. To the untrained eye, it is a pile of sand and gravel.

But closer inspection will reveal that it is a very old structure with sediments

that host valuable information about changing climate conditions from 28,000 years

ago to today. The early geologist and explorer Grove Karl Gilbert dubbed it the

Great Bar at Stockton; today it is known as the Stockton Bar. Measuring 3 kilometers

long, it is a sandbar remaining from Lake Bonneville, an enormous lake that existed

during the Pleistocene. No other feature in the Bonneville Basin contains as complete

and detailed a record of Lake Bonneville's history as does the Stockton Bar.

Part of Tooele

County, the Stockton Bar is also home to several historical sites, including a

1902 jail and a cemetery that dates to the late 1800s. People find it an excellent

location for horseback riding, picnicking and even hang gliding. The bar also

provides valuable habitat for various plants and animals and serves as green space

in an expanding urban environment.

Part of Tooele

County, the Stockton Bar is also home to several historical sites, including a

1902 jail and a cemetery that dates to the late 1800s. People find it an excellent

location for horseback riding, picnicking and even hang gliding. The bar also

provides valuable habitat for various plants and animals and serves as green space

in an expanding urban environment.

Old and new together:

This aerial view shows the Point of the Mountain spit, which sits at the south

end of the Salt Lake Valley. During the Pleistocene, this was the shoreline of

Lake Bonneville. This shoreline geoantiquity is a world-class paragliding and

hang gliding area that is being converted into high-density residential housing

(left). To meet urban growth needs, large amounts of sand and gravel are being

extracted from this Lake Bonneville landform. Photo supplied courtesy of hang

glider pilot Mark Bennett.

Like many of Lake Bonneville's remaining shoreline features, the Stockton Bar

is situated in an area of rapid urban growth and was recently targeted for destruction.

The bar is on privately owned land, and in 2000 the owner sought to obtain a grandfathered

permit to develop it for sand and gravel. The town of Stockton, which has a population

of about 400, sits beside the bar. Residents were concerned about the dust, trucks

and noise that might accompany a sand-and-gravel operation.

They were also eager to find out more about the Stockton Bar from an outside source

so that they were well informed before any decisions about permitting were made.

At the same time, our research team had received a grant from the National Science

Foundation (NSF) for multidisciplinary research on change in urban environments.

Our specific charge was to examine science-based strategies for evaluating and

making inventories of geologic features such as the Stockton Bar, and how to use

those strategies in preservation efforts. For example, the Stockton Bar is a prime

source of sand and gravel, but it is also a world-class geologic feature. It is

like a rare book that has all its pages. Why tear out pages and try to sell each

one individually? With an inventory of such landforms, we can decide which books

are complete and which are partial. It is better, for example, to extract sand

and gravel from the partial or already incomplete books. The complete books can

become heritage areas slated for preservation.

As it happened, Nicole Cline, a county planner from the Tooele County Planning

office, contacted us for information. We met with the county planners and provided

testimony during public hearings about the permit. We emphasized the Stockton

Bar’s geologic and historic value, noting that Gilbert had documented it

during his explorations in the 1800s. Using grant funds, we created brochures

about the geologic and historical significance of the Stockton Bar. The mayor,

Barry Thomas, arranged to send the brochures out with the town's water bills.

The issue reached the Tooele County planning commission, which requested that

we give a presentation about the bar’s geologic and scientific background.

Using our information and other presentations, the commissioners voted to deny

the permit. Public perception, fueled in part by the brochures we created, helped

a great deal in this decision.

During this process we learned many lessons, one being that our public information

campaign needed a catchier name than landform. We developed the concept of a geoantiquity,

defined as a natural record of Earth history that documents environmental change

on local, regional and global scales. These records are classics of Earth history,

written in nature's handwriting. They are geomorphic landscapes shaped by a host

of surficial processes. Our work in Stockton was the first step in what we hope

to become a national movement to preserve unique geoantiquities.

Geoantiquities can occur in nearly any location and setting. Our study focuses

on near-surface, well-exposed examples associated with the formation of Pleistocene

Lake Bonneville. The Bonneville Basin contains evidence of lakes, marshes, glaciers,

dunes, alluvial fans, deltas, floodplains and extensional tectonics. At the end

of the last major Ice Age, Lake Bonneville occupied much of western Utah, then

receded to the level of the modern Great Salt Lake as the climate became drier

and warmer. As the lake retreated, it left behind beaches, spits and other shoreline

deposits (28,000 to 15,000 radiocarbon years ago), many of which remain beautifully

preserved due to arid conditions.

These Pleistocene geomorphic features offer an invaluable opportunity to study

climate signals, such as temperature, extreme conditions, and wind directions

and strengths; hydrologic changes, such as lake history and river discharge; geodynamic

events, such as earthquake and volcanic markers; and other environmental parameters,

such as fires, biotic communities and unusual depositional events. Scientific

studies also relate to policy issues, such as hazard mitigation and environmental

quality.

Geoantiquity Heritage Areas

Urban development is rapidly changing our landscape. Meeting the resource needs

of a growing urban environment while maintaining benefits of open space and

important natural resources is a particularly challenging problem.

At the same time,

conservation of natural areas in the United States has primarily focused on

biological, ecological or aesthetic criteria. The National Environmental Policy

Act (NEPA) has been used to identify and protect scenic and biological qualities

of sites. Federal land agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management and the

U.S. Forest Service manage sites primarily for resource uses. And even though

some national parks have been set aside for their scientific value, only a small

number of sites are likely to make it into the National Park System.

At the same time,

conservation of natural areas in the United States has primarily focused on

biological, ecological or aesthetic criteria. The National Environmental Policy

Act (NEPA) has been used to identify and protect scenic and biological qualities

of sites. Federal land agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management and the

U.S. Forest Service manage sites primarily for resource uses. And even though

some national parks have been set aside for their scientific value, only a small

number of sites are likely to make it into the National Park System.

The geoantiquity concept parallels the well-established model of cultural resource

management for cultural antiquities (i.e., historic and archaeological sites),

in which sites of special importance are recognized and afforded legal protection.

Using this premise, the concept introduces the idea of geoconservation: protecting

areas based on scientifically important geological and geomorphological resources.

This concept is well-developed in Europe, but the existing legislative framework

in the United States does not provide appropriate protection for sites based

on geoconservation.

To remedy the lack of appropriate protection of scientifically important geological

and geomorphological resources, a geoconservation program must be initiated,

and deficiencies in environmental policies addressed. The purpose of our research

is to develop methods and applications for evaluating and managing earth science

sites, and to suggest specific policy reform to help accommodate such efforts.

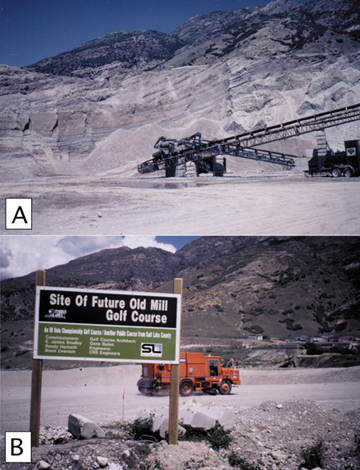

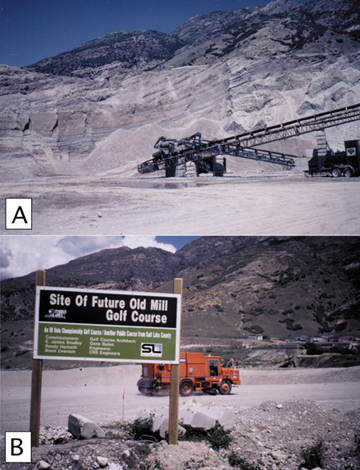

A:

A 1993 view of a large exposure of a Lake Bonneville delta at the mouth of Big

Cottonwood Canyon, Salt Lake City. This has also served as a quarry site for

sand and gravel.

B: By 1994, the sloping fronts of the delta were

remolded and regraded for conversion to a county golf course. Presently the

area is covered with manicured grass, and houses are rapidly being built along

the available paleo-shorelines just behind and overlooking the golf course.

Photos from Chan and Milligan, 1985

Our research on geologic landforms created by Pleistocene Lake Bonneville is

the first systematic attempt in the United States to apply geoconservation methods

of identification, evaluation and management. We propose that well-preserved

sites of unique geologic value be appointed as Geoantiquity Heritage Areas,

much in the same fashion as sites preserved for their cultural antiquities.

A Geoantiquity Heritage Area designation would not only protect the scientific

integrity of pristine geologic sites but would also provide valuable real estate

for a multitude of educational, historical and recreational uses. For example,

researchers have used the Stockton Bar to determine the detailed history of

what happened when Lake Bonneville was rising to its highest level. They have,

in turn, communicated this knowledge to the community through school field trips,

teacher workshops, local publications and public hearings.

Geologic time, human time

Humans can be agents of erosion and other processes leading to irreversible

change. The impact of humans can be permanent, and the loss of geoantiquities

is an impending reality, particularly near cities where land is privately owned

and urban growth is rapid. Human impact on geoantiquities can be dramatic over

time periods of just a few years, or happen over longer scales of decades to

centuries.

Loose, unconsolidated sediments are readily available sources of sand and gravel

for urban needs, but are easily disturbed and vulnerable to removal or burial,

particularly in areas with high growth rates, such as Utah's Wasatch Front,

which extends along the active Wasatch fault and crosses through urban areas

such as Salt Lake City.

Human activity here has already claimed some geoantiquities. It took only a

few years for high-end homes and housing tracts to encroach upon a quarry that

was once on the fringes of Salt Lake City. As a gravel quarry, it displayed

fine examples of large foresets, the sloping fronts of the lake's deltas. But

with the encroaching urbanization it was rapidly regraded, seeded with grass,

and turned into a golf course. Consequently, gravel operations relocated to

other previously pristine geoantiquities. This progression demonstrates the

changes that can happen to geoantiquities within just a few years.

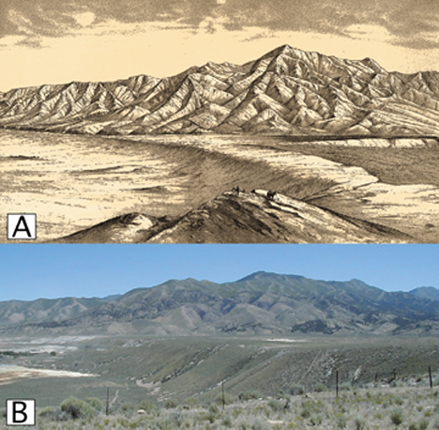

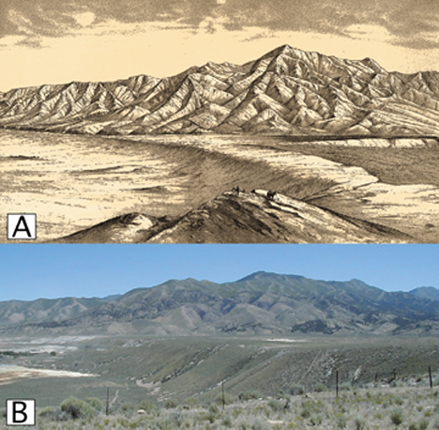

Another example of the rapid degradation of geoantiquities is the case of the

Warm Springs fan. This deposit was a small, post-Bonneville alluvial fan that

Gilbert's team studied and drew in 1890. The fan was deposited over approximately

10,000 years, but it took mere decades for the deposits to be removed and for

the area to be developed as an industrial park. Thus, the anthropogenic rate

of removal is approximately two to three orders of magnitude greater than the

natural rate of deposition.

If we or others had begun this geoantiquity research several decades ago, the

scientific and educational values of this fan might have at least been identified

and made known. With the fan removed, all that remain for scientific study are

pictures and descriptions such as Gilbert's.

Building partnerships for the

future

Our research

now focuses on compiling an inventory of geoantiquities in the Lake Bonneville

area. Planning commissions and special interest groups are aware of our efforts

and have contacted us for scientific information when development projects have

threatened to alter the landscape. An inventory is a key tool in the preservation

process, as it can help in prioritizing sites and identifying those most valuable

to science and education.

Our research

now focuses on compiling an inventory of geoantiquities in the Lake Bonneville

area. Planning commissions and special interest groups are aware of our efforts

and have contacted us for scientific information when development projects have

threatened to alter the landscape. An inventory is a key tool in the preservation

process, as it can help in prioritizing sites and identifying those most valuable

to science and education.

Partnerships between geologists and local and national governing bodies, special

interest groups, community organizations, scientists and educational leaders

are vital for raising awareness of geoantiquities, and can lead to protection

and integration of geoantiquities heritage areas in urban planning. Implementation

and evaluation of partnerships provide a model that can be transferred to other

projects in the region and nationally.

A: The

Stockton Bar (view to the northeast) depicted by Grove Karl Gilbert in the 1890

U.S. Geological Survey Monograph 1.

B: The Stockton Bar today (same view looking northeast).

It remains relatively intact, with excellent potential to be a geoantiquities

heritage area worth saving and preserving. Images supplied courtesy of Marjorie

Chan, University of Utah.

We are working with groups such as the Salt Lake County geologist's office,

which is putting in a county park near the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon

that overlooks glacial landform geoantiquities. Through our research, we can

help emphasize the scientific value of the geoantiquities using interpretive

signs. The Utah Museum of Natural History will be constructing a new "green"

building that will be close to the Bonneville Shoreline. We will offer input

into how they can plan their building to complement the shoreline, and how they

can use this geoantiquity in part of their educational outreach to visitors.

Education is an important tool for implementing geoconservation. Teachers can

instigate change as they interact with the many youth who will form our future.

Working with Genevieve Atwood, a master teacher and chief education officer

for the nonprofit organization Earth Science Education, we offered field workshops

for K-12 teachers to promote geoantiquities. Teachers learned what a geoantiquity

is, how to recognize one, the scientific relevance of geoantiquities, and the

societal and scientific value of geoantiquities. Exercise modules demonstrated

how geoantiquities could be integrated with other subjects such as environmental

science, ecology, mathematics, chemistry, geography, literature and art. Teachers

were positive and enthusiastic about how they could use their neighborhood landscapes

in teaching urban geoscience education. We expect that this will continue to

be an essential avenue for making the community aware of geoantiquities

Earth science research and information is the foundation of the geoantiquities

concept. It can help us provide logical methods of identification, evaluation

and designation of sites, which are critical. However, the success of geoconservation

equally rests upon the political and educational elements of land-use planning

and community involvement. Community support, based on awareness and appreciation

of how the landscape records and reveals Earth's history, will be key to the

future of geoconservation.

All the authors are at the University

of Utah:

Chan is a professor in and currently chair of the Department of Geology and Geophysics,

where she has taught for 20 years. Her research interests in sedimentary geology

have covered Precambrian through Pleistocene age deposits. E-mail: machan@mines.utah.edu.

Currey is professor of geography and director of the Limneotectonics Laboratory

in the Geography Department, where he has taught for 33 years. His research interests

are in the geomorphology of lakes, and in neotectonics and geodynamics of Quaternary

lakes.

Dion is currently a Ph.D. student in the Geography Department. Her research examines

the concept of geoconservation and constructing an inventory database for geoantiquities.

Godsey is currently a Ph.D. student in the Department of Geology and Geophysics.

Her research examines the geomorphic and stratigraphic record of the Stockton

Bar, and high-frequency lake-level changes in Lake Bonneville.

At the same time,

conservation of natural areas in the United States has primarily focused on

biological, ecological or aesthetic criteria. The National Environmental Policy

Act (NEPA) has been used to identify and protect scenic and biological qualities

of sites. Federal land agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management and the

U.S. Forest Service manage sites primarily for resource uses. And even though

some national parks have been set aside for their scientific value, only a small

number of sites are likely to make it into the National Park System.

At the same time,

conservation of natural areas in the United States has primarily focused on

biological, ecological or aesthetic criteria. The National Environmental Policy

Act (NEPA) has been used to identify and protect scenic and biological qualities

of sites. Federal land agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management and the

U.S. Forest Service manage sites primarily for resource uses. And even though

some national parks have been set aside for their scientific value, only a small

number of sites are likely to make it into the National Park System.

Part of Tooele

County, the Stockton Bar is also home to several historical sites, including a

1902 jail and a cemetery that dates to the late 1800s. People find it an excellent

location for horseback riding, picnicking and even hang gliding. The bar also

provides valuable habitat for various plants and animals and serves as green space

in an expanding urban environment.

Part of Tooele

County, the Stockton Bar is also home to several historical sites, including a

1902 jail and a cemetery that dates to the late 1800s. People find it an excellent

location for horseback riding, picnicking and even hang gliding. The bar also

provides valuable habitat for various plants and animals and serves as green space

in an expanding urban environment. Our research

now focuses on compiling an inventory of geoantiquities in the Lake Bonneville

area. Planning commissions and special interest groups are aware of our efforts

and have contacted us for scientific information when development projects have

threatened to alter the landscape. An inventory is a key tool in the preservation

process, as it can help in prioritizing sites and identifying those most valuable

to science and education.

Our research

now focuses on compiling an inventory of geoantiquities in the Lake Bonneville

area. Planning commissions and special interest groups are aware of our efforts

and have contacted us for scientific information when development projects have

threatened to alter the landscape. An inventory is a key tool in the preservation

process, as it can help in prioritizing sites and identifying those most valuable

to science and education.