At about 8,000

feet above sea level, tucked into the east side of the Sierra Nevada mountain

range in California, is Mammoth Lakes — a popular ski resort area and home

of a 40-megawatt geothermal plant. There, superheated waters from magma in Earth's

crust circulate through wells without ever coming into contact with the surface.

The geothermal fluids heat a secondary fluid that then boils and spins a turbine,

creating electricity for the area.

At about 8,000

feet above sea level, tucked into the east side of the Sierra Nevada mountain

range in California, is Mammoth Lakes — a popular ski resort area and home

of a 40-megawatt geothermal plant. There, superheated waters from magma in Earth's

crust circulate through wells without ever coming into contact with the surface.

The geothermal fluids heat a secondary fluid that then boils and spins a turbine,

creating electricity for the area. Although just a couple hundred yards off the main highway between Los Angeles and Reno, the Mammoth Pacific Power Plant is hard to spot, says Gordon Bloomquist of the Washington State University Cooperative Extension Energy Program. "I've been up in the ski area and tried to look for it from up there and even knowing where it's located … I couldn't find the plant."

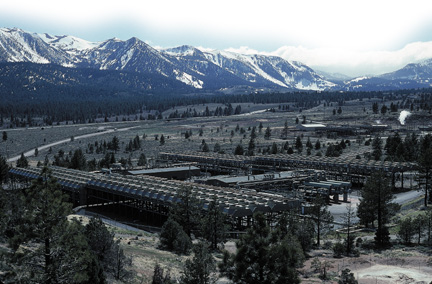

The green-painted, 40-megawatt Mammoth Pacific Power Plant is camouflaged in this valley east of the Sierra Nevada range in California. A recent federal report on geothermal development could motivate construction of similar plants at top geothermal sites in the western United States. Photo courtesy of Geothermal Resources Council and the National Renewable Energy Lab.

Mammoth Pacific features some of geothermal energy’s more attractive qualities, Bloomquist says, including environmental aesthetics, relatively small footprint of a couple of acres and low-emissions. But geothermal development has experienced a significant dry period over the past 20 years, due, in part, to long delays in the leasing of land. A new report released in April by the Departments of Energy and the Interior, however, aims to begin reversing that trend and to spur a new growth in geothermal energy development.

Motivated by a new emphasis on renewable energy in President Bush's National Energy Plan, the report focuses on areas in the western United States that have the highest near-term potential (two to three years) for the development of geothermal energy. It identified 35 "top-pick" sites in six western states: California, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah and Washington.

By honing in on specific areas in each state, the Bureau of Land Management can prioritize funding toward the local leasing offices where geothermal power resources are high. "Now they'll know which field offices to support, and can go through planning processes to determine whether those lands are available for geothermal leasing and development," says report co-author Barbara Farhar of the National Renewable Energy Lab.

Currently, only four states produce geothermal energy — Hawaii, California, Utah and Nevada. California ranks highest, with 7 percent of its energy coming from geothermal energy, while the rest of the nation barely draws 1 percent of its supply from geothermal power.

"There are only a small number of areas where you actually have heat close enough to the surface to be economically exploitable," Bloomquist says. Although other states have the near-source magma and heat to support geothermal development, land access restrictions and a poor market have hampered its progress in those states.

When Bloomquist first began working in Washington in 1978, the state had more than 1 million acres under lease application for geothermal development. Only about 70,000 acres ended up getting leased, Bloomquist says. Now, the state has lease applications that have been pending more than 10 years.

According to the geothermal report, as of May 23, 2002, there were 316 leases and 297 pending lease applications for geothermal development across the nation, with at least 83 of those applications more than 25 years old. In 1985, more than 680 leases existed on more than 2 million acres of land.

The decline in development and delay in leasing land for geothermal stems from several problems, including a lack of funding and general attention by industry and government, Farhar says.

It is also the result of leasing agencies using high development numbers in evaluating the environmental effects of leasing — for example, using 1,000 megawatts per square mile as a standard development figure, Bloomquist adds. Such a large output on a small area would necessitate a large infrastructure — more power plants and wells — and create a larger environmental footprint — greater air emissions, water usage and noise levels. "There's almost no place on Earth where there's 1,000 megawatts per square mile and so if you use that worst-case scenario, the environmental impact would be significant," he says.

After the passage of the Geothermal Steam Act in 1970, which opened up federal lands for geothermal leasing, The Geysers in California was the only major producing area in the United States. The world's largest geothermal energy field, The Geysers was producing about 1,000 megawatts per 5 square miles, Bloomquist says. With such little experience to draw on, no one knew then what the maximum production number was when putting together leasing standards.

Aside from these land access problems, geothermal also faces a tough market. Although more states are passing Renewable Portfolio Standards, which require that a certain percentage of their energy supply come from renewable energy, geothermal energy has yet to be competitive as a renewable resource, Bloomquist says.

"Even if we got all the leases that are pending issued in the next couple of years, you still wouldn't see any rush to build new power plants until you have more Portfolio Standards passed and until you get a production tax credit — or something to reduce the cost of geothermal power." Offset by a tax credit, wind power, for example, costs a couple of cents less per kilowatt-hour than geothermal power, he adds.

Still, geothermal proponents are hopeful that the new report will help speed up the leasing process enough so that utilities and developers can step in when the economics are better. Citing a comprehensive federal report on solar, wind, geothermal and biomass energy sources released in February, Farhar says she is happy to see the country placing more emphasis on these potentially significant contributors. "Now that we realize we must have a domestic energy resource, we must consider renewable resources very seriously for our nation's energy supply."

Lisa M. Pinsker

Back to top