Every few

years, the trade winds of the equatorial Pacific slacken, allowing warm water

in the west to slosh eastward and start an El Niño. Related to the ocean

warming are atmospheric changes, called the Southern Oscillation, which disrupt

climate worldwide — bringing drought and fire to some areas and torrential

rain and floods to others. These events, together known as ENSO, may be more

predictable than previously thought, according to a new climate model tested

with a century and a half of data.

Every few

years, the trade winds of the equatorial Pacific slacken, allowing warm water

in the west to slosh eastward and start an El Niño. Related to the ocean

warming are atmospheric changes, called the Southern Oscillation, which disrupt

climate worldwide — bringing drought and fire to some areas and torrential

rain and floods to others. These events, together known as ENSO, may be more

predictable than previously thought, according to a new climate model tested

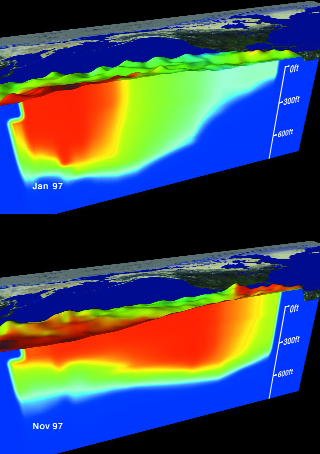

with a century and a half of data. These Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer images show the 1997-1998 El Niño, with a view of the sea surface before the event (left), with warm Pacific waters in the west, and during the event (right), with warm Pacific waters shifted to the east. The bumps are sea-surface height, and the colors are sea-surface temperature. Red is 30 degrees Celsius and blue is 8 degrees Celsius. A new model suggests that predicting such events several years in advance may be possible. Images courtesy NASA.

Dake Chen, an oceanographer at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) at Columbia University, and colleagues tested their new model with historical weather data collected between 1857 and 2003, the longest period over which any model has been used to forecast ENSO events. The coupled ocean-atmosphere model successfully predicted all of the larger ENSO events during that period, but it was not as capable of predicting the smaller ones, according to their study published in the April 15 Nature. For some large events, the results showed lead times of up to two years. Previous successful ENSO models predicted events about six to nine months in advance.

The model, however, not only predicted those ENSOs that occurred but also some that did not. “The authors’ results suggest that false alarms are limiting their model’s forecast skill at long lead times,” says Andrew Wittenberg, a climatologist with NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. He adds that the challenge for all ENSO models, including the LDEO one, “will be to hit the big ENSO events without giving too many false alarms.”

Scientists have long struggled to model the complex interactions between the ocean and atmosphere of the tropical Pacific. Chen’s co-authors and LDEO colleagues, Mark Cane and Steve Zebiak, developed the first successful coupled ocean-atmosphere model, which predicted the 1986-1987 ENSO. Chen’s recent study is the latest in the ongoing debate about how predictable ENSO really is.

On one side, researchers argue that chaotic forces in the atmosphere vary so much from event to event that long-term prediction may be impossible. On the other side, researchers say that what really matters are the initial starting conditions — the sea-surface temperatures and prevailing winds present at the onset of an ENSO cycle. “If ENSO is a self-sustaining oscillation controlled by internal dynamics, it should be predictable at long lead times,” Chen says.

Because his team’s model was able to predict every major ENSO in the last 150 years without accounting for atmospheric chaos, Chen and his colleagues say that it shows these forces are not as influential as previously thought. And, if climatologists can correctly determine at what point a particular ENSO is in its cycle, they may be able to predict future peaks up to two years in advance.

However, such methods and their results still need further testing, says David Anderson, a climatologist at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in Reading, England. In an accompanying Nature commentary, Anderson questioned whether the model’s “success in predicting the future (will) match that of its performance in predicting the past.”

Chen says they will soon find out. The team expects to post long-lead forecasts on the research group’s Web site shortly. “I believe we should be able to predict large El Niños two years in advance,” he says, “though I am less confident in the predictability of small events.”

The outcome of the debate over whether long-term prediction is truly possible could mean the difference between a warning of a>> few months and one of a few years for regions of the world affected by the severe weather ENSO may bring.

“Models are essential for understanding and predicting ENSO, which is by far the largest and most influential short-term climate fluctuation in Earth’s climate system,” Chen says. “Long-lead forecasts of ENSO will not only benefit the tropical countries that are directly under the influence of ENSO, but also improve our ability to manage disastrous floods and droughts in many parts of the world.” His model, he says, provides hope for early forecasting of ENSO events.

Sara Pratt

Geotimes contributing writer

Back to top