Geotimes

Feature

Petra: An Eroding

Ancient City

Naomi Lubick

Sidebars:

Preserving

an Afghan landmark

Conservation changes

Tucked into

desert canyons in southwestern Jordan, carved stone facades cover red sandstone

walls, tens of meters high. Just inside the rock faces, benches line cavernous

rooms hewn there thousands of years ago. The red rock walls ring the ancient

city of Petra, where expert stonemasons made the monuments for gods, kings and

wealthy citizens.

Tucked into

desert canyons in southwestern Jordan, carved stone facades cover red sandstone

walls, tens of meters high. Just inside the rock faces, benches line cavernous

rooms hewn there thousands of years ago. The red rock walls ring the ancient

city of Petra, where expert stonemasons made the monuments for gods, kings and

wealthy citizens.

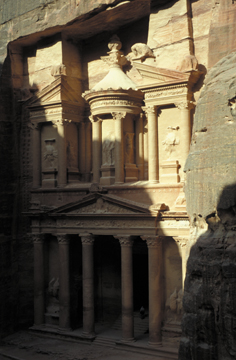

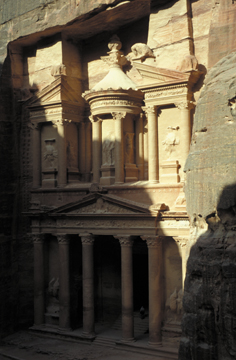

The Al Khazneh, also known as the Treasury,

is the largest monument in Petra. It sits at the entrance to the city, greeting

thousands of visitors to this cultural icon every year. All photographs by and

courtesy of Tom Paradise.

The carved rocks remain as a seemingly timeless testimony of human ingenuity

and survival in a desert that gets 15 centimeters of rain a year. Well-established

by the third century B.C., by which time a formerly nomadic people called the

Nabataeans had moved into the region, Petra became a major center of commerce

by the first century B.C. By the time the Romans took over the desert metropolis

around A.D. 100, a complex integrated system of hand-carved stone flumes (some

lined with ceramic pipes), reservoirs and 200 cisterns was capable of supplying

as much as 12 million gallons of water a day to the settled valley.

Enough to meet the needs of 100,000 people in a modern-day American city, the

water system gave life to gardens, animals and a rich urban culture in the middle

of the desert, supported by a booming spice and textile trade route. At its

height, Petra may have been home to at least 20,000 people, according to archaeologists

and curators of an exhibition of Petra artifacts in the United States, which

opened at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York last fall

and will move to the Cincinnati Art Museum in September.

“Petra is all about water, both its productivity when harnessed and its

power of devastation when left uncontrolled,” says Glenn Markoe, curator

at the Cincinnati Art Museum. The city, which went by different names over the

centuries, had “a really elaborate water management scheme that people

are just understanding now,” Markoe says. However, the flash floods that

created the site’s canyons millions of years ago are now threatening to

destroy it, aggravated by the increasing number of humans who flock to see what

remains of the ancient site.

Controlling the flow

The sandstone

that forms Petra’s red-faced monuments is the oldest in a series of sandstone

formations, underlain by a pre-Cambrian granite with gneiss and schist. The

oldest sandstone consists of coarse- to medium-grained quartz clasts, shot through

with an iron- and manganese-rich matrix, and varies in color from red to yellow

to chocolate.

The sandstone

that forms Petra’s red-faced monuments is the oldest in a series of sandstone

formations, underlain by a pre-Cambrian granite with gneiss and schist. The

oldest sandstone consists of coarse- to medium-grained quartz clasts, shot through

with an iron- and manganese-rich matrix, and varies in color from red to yellow

to chocolate.

Geologists have identified the formation as the remnant of a large braided stream

complex, which was then buried by another white, friable sandstone formation;

a limestone layer caps high points throughout the region. The surrounding hills

are covered with Holocene wind and stream deposits, but little vegetation. Weathering

and regional seismicity exacerbate cracking and jointing of the sandstones.

But when Petra was a thriving city, its intricate water management system helped

buffer it from erosion.

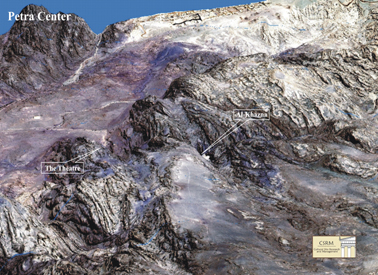

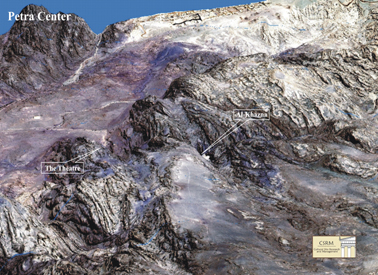

This digital elevation model shows the topographic relief around Petra and the

position of two major sites, the Treasury (Al Khazneh) at the end of the Siq

and the Roman-Greek amphitheater (The Theater), about a mile away. The city

of Petra extends onto the floodplain in the upper left. Image by T. Nirundorn,

courtesy of Cultural Site Research and Management.

Beginning in the 1990s, a team of archeologists from Brown

University, led by Martha Sharp Joukowsky, uncovered a civic complex with

a garden and central pool at the heart of Petra. The complex anchors the end

of the town’s main street, which roughly bisects the valley between Petra’s

monument-carved cliffs. The street itself follows an old ephemeral stream floodplain,

or wadi.

The Nabataeans prevented floods from destroying the city through a damming system

that diverted water from the wadi. They also lined the Siq — a gorge or

narrow chasm that leads from the outside desert to the entrance of the old city

and one of Petra’s largest monuments, known as the Treasury — with

water channels. This system of channels and dams controlled water flow and erosion,

and provided irrigation water to the settlement.

In addition to archeological investigations, satellite imagery is revealing

just how sophisticated the Nabataeans were “in terms of sculpting the ground

and the rock face to facilitate the natural flow of rainwater. That’s the

way they could keep erosion minimized,” Markoe says. “It’s the

breakdown of that system over the past centuries that is contributing to the

environmental hazard.” Sand deposits and rocks carried by flash flooding

now bury the courtyard and steps that once led up to the imposing facade of

the Treasury, Markoe says — piled more than 20 feet thick, “dramatic

evidence of how quickly flash flooding can devastate the site,” he says.

Nature at work

Petra sits on the western edge of the Arabian plate, southeast of the Dead Sea;

the sandstone outcrops extend north on the eastern side of the transform fault

segment of the Dead Sea rift zone (the fault zone becomes a spreading rift farther

south). An earthquake timeline from the AMNH/Cincinnati Art Museum exhibition

lists around 20 major seismic events in the greater region.

Fallen stone columns that lined Petra’s main street tell the story of the

earthquake and aftershocks that overwhelmed the city in A.D. 363, also described

in papyrus documents written to a Byzantine bishop. Approximately 800 carved

cliff monuments survived, but the living city of Petra died — trade routes

had shifted sometime in the previous century, and historians conjecture that

the community lacked the wealth to rebuild its central town structures after

the temblors.

Without any maintenance, Petra’s water system crumbled. The Nabataean dams

and canals no longer diverted water flow away from the tombs and town —

making the sandstone that composes most of Petra’s monuments and its Nabataean

Roman-style theater (which seats 12,000 to 15,000 people) once again susceptible

to accelerated weathering.

Fractures across

the region, worsened by weathering and seismicity, collect water, which leads

to spalling — the freezing and thawing that widen cracks behind the rock

faces, eventually popping the outer layers off. Studies sponsored by the World

Heritage Center, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO), and which designated Petra as a World Heritage Site in

1985, showed that salt deposits from the irrigation systems and other water

table problems contributed to sandstone weathering and erosion. Ironically,

the flooding that created the region’s canyons now threatens to fill them

or erode away the human structures there. The shops that once lined the town

are now filled with flood deposits.

Fractures across

the region, worsened by weathering and seismicity, collect water, which leads

to spalling — the freezing and thawing that widen cracks behind the rock

faces, eventually popping the outer layers off. Studies sponsored by the World

Heritage Center, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO), and which designated Petra as a World Heritage Site in

1985, showed that salt deposits from the irrigation systems and other water

table problems contributed to sandstone weathering and erosion. Ironically,

the flooding that created the region’s canyons now threatens to fill them

or erode away the human structures there. The shops that once lined the town

are now filled with flood deposits.

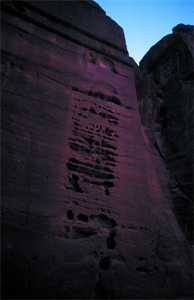

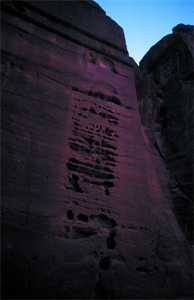

Water, wind and insolation have eroded

the walls of this tomb facade in the Outer Siq in Petra, creating a honeycombed

pattern of cavities called tafoni.

Conventional wisdom also holds that weathering in such dry places should be

greatest on southern rock faces, which get the most sun exposure, says Tom Paradise,

a geomorphologist from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, who has been

studying Petra for 20 years. However, in his studies there in the late 1980s

and mid-1990s, Paradise says, “what I found was that the greatest weathering

was on western faces, where you get wetting from storms, rain and sun.”

And Paradise found considerable weathering on eastern faces as well, where morning

dew and sun combined daily.

“It’s these little tiny super-frequent events, like wetting and drying

from dew every morning, that causes the sand to disaggregate,” he says.

Paradise documented the rates of weathering on rock faces all over Petra, meticulously

noting angle of the sun, precipitation at dawn, temperature, lithology and the

eroded spots in the monuments and elsewhere around the city — as well as

how fast such cavities grew over time. He calculated that some sandstones weathered

as much as 2.5 centimeters in 100 years.

Since then, Paradise says, he revisited his work on Petra’s Greco-Roman

theater, which he mapped with lasers for his dissertation in the late 1980s

to recreate its exact profile. A few years ago, while checking his work, he

found that the original stonemasons’ carved chisel marks — that had

remained plain on the rocks’ surfaces for centuries — had worn away

in some places. In just the few decades that Paradise has worked in Petra, he

says, millennia-old surfaces are gone. The puzzle he faced was why something

that had lasted so long could erode so quickly, when other conditions in the

region had not changed.

People at work

While watching

tourists climb the stairs in Petra’s theater several years ago, Paradise

says he had an epiphany. “People don’t behave as well” as they

did several decades ago and during ancient times 2,000 years ago, he says. Hordes

of people now leave their marks on the cut-rock theater as “they climb

all over the seats.”

While watching

tourists climb the stairs in Petra’s theater several years ago, Paradise

says he had an epiphany. “People don’t behave as well” as they

did several decades ago and during ancient times 2,000 years ago, he says. Hordes

of people now leave their marks on the cut-rock theater as “they climb

all over the seats.”

Petra’s Greek- and Roman-influenced

amphitheater holds seating for 15,000, but erosion from modern tourists scrambling

across the sandstone seats is accelerating as more people have come to visit

the ancient World Heritage Site.

Paradise also noted some seemingly simple shifts in human habits: “Tourists

are all wearing … the best shoes, with soles that grab on everything,”

he says, instead of the rubber-soled working boots or soft sneakers they wore

several decades ago. “We’re ignoring this huge factor and it’s

called us,” Paradise says.

As Paradise was observing these changes to his field site, the yearly number

of visitors was close to peaking. Since European explorers first documented

Petra in the 19th century, modern tourists have flocked to the site, which has

been labeled as the biblical city of Edom. Petra became a destination for busloads

of people ready to walk through the Siq, for religious tours, or to see theTreasury,

featured in the movie “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.”

The once relatively unknown city attracted at least half a million people in

2000, says Doug Comer, an archaeologist who runs a company called Cultural Site

Research and Management, in Baltimore, Md., which currently advises the organizations

that manage Petra. “That’s a lot of people in a site that 20 years

before was getting maybe 30,000,” he says.

The crowds of modern people visiting Petra have left many unexpected marks on

the ancient rocks, Paradise says, and they have accelerated the natural processes

at work. When Petra became a World Heritage Site in 1985, the Bedouin tribes

who had settled in the area were forced to leave the caves they had made home

(living in the monuments’ large rooms lined with rock-carved benches that

the Nabataeans had used as ritual banquet halls). But Bedouin people now run

tours of the site, bringing an influx of money to their community, according

to researchers who work there.

Paradise’s students monitored how people in those tour groups behaved,

from where they put their hands to where they placed their feet. The students

then looked at what had disappeared. “One whole chunk of wall of the Khazneh

[the Treasury] had lost sand because that’s where tour guides let people

sit” while they talked about the history of the site, Paradise says, leading

to a loss of half a cubic meter of sandstone over a few years.

Even the dark inner caves of the monuments carved by the Nabataeans and others

have suffered: “With more than 30 people entering the Khazneh, the humidity

jumped to levels that are unacceptable to preserve sandstone,” Paradise

says. Plus, the appearance of odd white deposits on the walls inside the Treasury

led Paradise to take a sample, assuming it was some kind of salt deposit growing

in flower-like structures on the surface. But, he says, lab tests showed the

deposits to be stearic acid — or beef fat, once a component of cheap suntan

oil in the Middle East. “People would rest by leaning against the wall

with sweating hands,” Paradise says, leaving a scum of fat behind. “This

is when you realize, ‘This is bad.’”

Paving the way

After September 11, 2001, “everything stopped,” Comer says. “Tourism

still hasn’t recovered in Petra.” This breather may be an opportunity

for establishing better management of the region, toward which Jordan’s

government and other organizations are working.

Needs as basic as adequate restroom facilities had been left unmet for years,

leaving tourists to use the tombs, Comer says. Medical services are unavailable

(heart attacks are a problem, owing to the average age of tourists, the heat

and the amount of walking necessary to see the site), he notes, and a lack of

personnel to guard the site makes theft of antiquities a constant concern. In

2001, Petra’s Jordanian caretakers closed the Treasury to visitors to control

humidity impacts, but people still sneak in, Paradise says.

Comer, who recently retired from leading the applied archaeology center for

the U.S. National Park Service, says that U.S. national parks protect a resource

“by steering people away from the sensitive parts,” and then educating

them in a separate space. Parks like Zion and the Grand Canyon are “like

Petra without the archaeology,” Comer says. Studies show that of the 5

million visitors that go to the Grand Canyon every year, the majority look at

it for about 20 minutes, but stay in the region for three days — impacting

the entire region on a greater scale. “Most don’t go into the canyon,

which is good, because if they did, it would be destroyed,” he says.

But guiding that experience in Petra remains challenging, Comer says. In Petra,

most tourists walk in, bring their own food, wander uncontrolled, and often

leave the same day on tour buses, without spending money in the region. That’s

something Comer and other parties involved would like to change, persuading

tourists to stay the night at local hotels and buy food locally.

In 1996, Comer led an analysis of how to manage and control all impacts to the

site, completing a report for the International Council on Monuments and Sites,

which is the cultural arm of UNESCO that advises the World Heritage Center.

In 2000, he and a group of advisors from the U.S. National Park Service, along

with Jordanian stakeholders, laid out the organizational structure necessary

to run Petra as a national park, “down to how many square meters of office

space they needed,” he says. In collaboration with the Jordanian Ministry

of Tourism and Antiquities, tourism groups, the Bedouins and nongovernmental

organizations, Comer and his team have moved forward to implement their management

plan.

Comer recruited four former U.S. National Park Service superintendents, including

the former head of Zion National Park in Utah, to work in Jordan with Petra’s

stakeholders. So far, the American team has worked out the relationships between

the different parties involved in running Petra, from park staff to independent

tour leaders to government agencies. But the advisory group is scheduled to

leave the region in June; Comer hopes that their tenure might be extended for

two more years.

For now, the restoration and conservation projects completed for the region,

listed by the Petra National Trust on its Web site, include rebuilt channels

that once carried water through the Siq. Future projects include such basics

as trail building and animal control measures, as well as an in-depth water

catchment study to determine fundamental information about how water moves through

the area. Comer’s company created digital elevation models in order to

determine the flood regime for the region. Future studies documenting weathering

and erosion will inform management of the site, Comer says. “The biggest

preservation problem is no doubt the tombs.”

Paradise says he intends to return in 2005 with his students to continue his

weathering research — and people-watching. “This is where I think

earth science has to go,” he says. “The only way to help things down

there is through good management.”

Preserving

an Afghan landmark

From

construction in the fourth to seventh century A.D. until just three years

ago, two giant Buddha statues resided about a quarter of a mile apart in

the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan, marking the entrance to hundreds

of caves adorned with fresco art. The two statues, at about 180 and 125

feet tall, were the world’s largest standing Buddhas and among the

oldest such representations. But in March 2001, they met their demise at

the hands of the Taliban. Since then, people have been working to preserve

the cultural site and discussing whether or not to rebuild the statues. From

construction in the fourth to seventh century A.D. until just three years

ago, two giant Buddha statues resided about a quarter of a mile apart in

the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan, marking the entrance to hundreds

of caves adorned with fresco art. The two statues, at about 180 and 125

feet tall, were the world’s largest standing Buddhas and among the

oldest such representations. But in March 2001, they met their demise at

the hands of the Taliban. Since then, people have been working to preserve

the cultural site and discussing whether or not to rebuild the statues.

Before its destruction by the Taliban in 2000, the larger of Afghanistan’s

two 1,800-year-old Buddha statues stood 180 feet tall. Now an empty niche,

the space that once held the large Buddha is still surrounded by 700 living

chambers and worship halls carved into the sandstone cliffs lining Afghanistan’s

Bamiyan Valley. Courtesy of Michael Urbat, University of Cologne, Germany.

From at least 300 B.C., central Afghanistan marked the confluence of ancient

civilizations in China, India, Rome, Greece and Persia. Merchants, artisans,

explorers and Buddhist monks traveling the famed Silk Road all passed through

Bamiyan, an oasis between two mountain ranges. Settling there, Buddhist

monks carved 700 living chambers and temples deep inside the valley’s

soft red sandstone cliff over the following several centuries.

Together with Greek artisans, the monks later decorated the chamber walls

with ornate and colorful frescoes. They also began carving the Buddha statues

directly out of the cliffs in huge niches, and carved staircases leading

up to the top of the statues’ heads. By covering the carvings with

mud and straw, the workers were able to fashion minute details such as facial

expressions and folds of clothing. They then plastered the entire statues

to preserve the detailing, and finally painted the Buddhas and gilded them

with gold.

The statues survived in the Bamiyan Valley more than a thousand years, through

conquering hordes, complete abandonment, strong earthquakes, desert weathering,

water intrusion and civil wars. But in 2001, after announcing its plan to

eradicate anything deemed idolatrous or that represented non-Islamic ideals,

the Taliban ignored pleas from the United Nations and countries around the

world, and destroyed the statues with dynamite.

Classified as a World Heritage Site in 2003, the entire Bamiyan site is

now in further danger. The Bamiyan cliffs are composed of a sequence of

conglomerates interbedded with fine-grained layers. And these same soft

Miocene sediments that allowed the artisans to carve the caves and Buddhas

now threaten the stability of the cliffs, especially after the 2001 explosions,

says Michael Urbat, a geologist at the University of Cologne in Germany.

Shoring up the collapsing niches that the Buddhas had occupied and the unstable

cliffs is the first priority for the United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), says Christian Manhart, the organization’s

Afghanistan specialist. UNESCO has planned preservation efforts to prevent

further deterioration of the few frescoes still in the caves and potential

looting of the Buddha and fresco remains. He says 26 caves with paintings

remain, as well as fragments of the stone Buddhas up to 2 to 3 meters in

size. And though they are hardly visible, parts of the Buddhas’ shoulders

and arms also remain intact in the niches. “We need to save what is

there,” Manhart emphasizes.

Stabilization of the cliffs began last year, Manhart says. Commissioned

by UNESCO, an Italian engineering firm has been filling cracks in the Buddha

niches as well as anchoring very loose parts of the cliffs to the ground.

The firm has also been stabilizing the staircases and began securing the

back walls of the niches in April.

At the same time, other groups are moving forward with reconstruction efforts.

Using pictures of the Buddhas, Armin Gruen, a photogrammetrist from the

Institute of Geodesy and Photogrammetry in Switzerland who is working with

New 7 Wonders Society and the Afghanistan Museum in Switzerland, created

a 3-D computer model of the larger Buddha that is “as complete and

precise as possible for physical reconstruction,” he says. His next

step is to create structural models at different scales based on the 3-D

computer model.

Urbat and colleague Klaus Krumsiek are also working on reconstructions,

but reassembling the remaining fragments from a geological perspective.

“We figured that only a method based on geological criteria is suitable

to reconstruct the original position of blasted rock fragments,” Urbat

says. The basic idea, he explains, is to use paleomagnetic indicators to

match patterns on the back wall of the niche to any patterns on the remaining

Buddha rock fragments. At the request of UNESCO, Urbat visited Bamiyan in

2003 to test his method and found that he could indeed match the rock fragments

to locations in the niches, which could help in reassembly efforts.

Debate continues as to how exactly to reconstruct the Buddha statues and

even if it is a good idea. Manhart says that no one has been granted permission

from the Afghan government to reconstruct the statues, and for now, “we

must prioritize resources on preserving what remains in Bamiyan.” He

says that he also worries that any reconstruction work might cause further

damage to the parts of the Buddhas that remain in the cliffs. For now, the

government of Bamiyan is providing armed guards at the cliffs to prevent

looting or destruction of what remains.

Megan Sever

Back to top |

Conservation

changes

Methods to preserve regional treasures have changed over the past century,

as archaeologists, geoscientists and historians recalibrate their thinking

about conservation and restoration.

In Italy, conservationists once peeled off the lichen growing on historic

buildings, says Tom Paradise, a geomorphologist at the University of Arkansas,

Fayetteville, who works on erosion in historic sites. But now, they recognize

that lichens in some settings act as a natural seal that can protect rocks

from erosion and weathering.

And in Petra, Paradise says, one proposed method in the past to preserve

the rock faces would have actually destroyed them if applied. Researchers

wanted to apply a type of silica gel to the rocks, which Paradise calls

“a pretty amazing product” for statues, which can be dipped into

the sealant and allowed to soak it up over days. “If it’s done

perfectly and every pore is sealed, it works great,” he says, “but

if it has one little crack in it, it concentrates moisture,” which

accelerates weathering in the long run and may cause spalling (where outer

rock layers peel after freezing and thawing).

Ideas on restoration, however, have changed most with regard to reconstruction

of sites, says Doug Comer, an archaeologist who worked for much of his career

for the U.S. National Park Service. At the turn of the century, in Turkey

and Greece, archaeologists who excavated sites restored them after finding

pieces and putting them back together “as best they knew how,”

Comer says, but their work was all “speculative.” Archaeologists

today might reconstruct the sites very differently, and they still would

only approximate how they first appeared to people living at the time.

And information can be lost when an archaeological site is changed: In Petra,

archaeologists have re-stacked the fallen columns that lined the main street

of the city of Petra, destroying evidence of the earthquake that initially

toppled them. Such “anastylosis” — or reconstruction of buildings

— is still common.

Alternatives are available, says Comer, who uses digital elevation models

and remote sensing to reconstruct archaeological sites. He says he can imagine

that scientists eventually will construct their own digital restorations,

perhaps visible only in a handheld virtual reality model that a tourist

would carry around a site. “It’s better to make an image that’s

speculative than a restoration that’s speculative,” he says. “It

costs less,” and, if the model is wrong, Comer adds, the impact is

“nothing like what you’re doing with bricks and mortar.”

NBL

To see a digital reconstruction of Petra’s

downtown temple, go to links below.

Back to top

|

Lubick is a staff writer

for Geotimes.

Links:

"Exploring

Petra: A Web Tour," Martha Joukowsky et al., Brown University

"The

Pool Complex of Petra," Leigh Ann Bedal, University of Pennsylvania

Cultural

Site Research and Management Web site

Tom

Paradise's Web site

AMNH

Web site for Petra exhibit

Petra

National Trust

Back to top

Tucked into

desert canyons in southwestern Jordan, carved stone facades cover red sandstone

walls, tens of meters high. Just inside the rock faces, benches line cavernous

rooms hewn there thousands of years ago. The red rock walls ring the ancient

city of Petra, where expert stonemasons made the monuments for gods, kings and

wealthy citizens.

Tucked into

desert canyons in southwestern Jordan, carved stone facades cover red sandstone

walls, tens of meters high. Just inside the rock faces, benches line cavernous

rooms hewn there thousands of years ago. The red rock walls ring the ancient

city of Petra, where expert stonemasons made the monuments for gods, kings and

wealthy citizens.

The sandstone

that forms Petra’s red-faced monuments is the oldest in a series of sandstone

formations, underlain by a pre-Cambrian granite with gneiss and schist. The

oldest sandstone consists of coarse- to medium-grained quartz clasts, shot through

with an iron- and manganese-rich matrix, and varies in color from red to yellow

to chocolate.

The sandstone

that forms Petra’s red-faced monuments is the oldest in a series of sandstone

formations, underlain by a pre-Cambrian granite with gneiss and schist. The

oldest sandstone consists of coarse- to medium-grained quartz clasts, shot through

with an iron- and manganese-rich matrix, and varies in color from red to yellow

to chocolate.  Fractures across

the region, worsened by weathering and seismicity, collect water, which leads

to spalling — the freezing and thawing that widen cracks behind the rock

faces, eventually popping the outer layers off. Studies sponsored by the World

Heritage Center, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO), and which designated Petra as a World Heritage Site in

1985, showed that salt deposits from the irrigation systems and other water

table problems contributed to sandstone weathering and erosion. Ironically,

the flooding that created the region’s canyons now threatens to fill them

or erode away the human structures there. The shops that once lined the town

are now filled with flood deposits.

Fractures across

the region, worsened by weathering and seismicity, collect water, which leads

to spalling — the freezing and thawing that widen cracks behind the rock

faces, eventually popping the outer layers off. Studies sponsored by the World

Heritage Center, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO), and which designated Petra as a World Heritage Site in

1985, showed that salt deposits from the irrigation systems and other water

table problems contributed to sandstone weathering and erosion. Ironically,

the flooding that created the region’s canyons now threatens to fill them

or erode away the human structures there. The shops that once lined the town

are now filled with flood deposits. While watching

tourists climb the stairs in Petra’s theater several years ago, Paradise

says he had an epiphany. “People don’t behave as well” as they

did several decades ago and during ancient times 2,000 years ago, he says. Hordes

of people now leave their marks on the cut-rock theater as “they climb

all over the seats.”

While watching

tourists climb the stairs in Petra’s theater several years ago, Paradise

says he had an epiphany. “People don’t behave as well” as they

did several decades ago and during ancient times 2,000 years ago, he says. Hordes

of people now leave their marks on the cut-rock theater as “they climb

all over the seats.”  From

construction in the fourth to seventh century A.D. until just three years

ago, two giant Buddha statues resided about a quarter of a mile apart in

the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan, marking the entrance to hundreds

of caves adorned with fresco art. The two statues, at about 180 and 125

feet tall, were the world’s largest standing Buddhas and among the

oldest such representations. But in March 2001, they met their demise at

the hands of the Taliban. Since then, people have been working to preserve

the cultural site and discussing whether or not to rebuild the statues.

From

construction in the fourth to seventh century A.D. until just three years

ago, two giant Buddha statues resided about a quarter of a mile apart in

the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan, marking the entrance to hundreds

of caves adorned with fresco art. The two statues, at about 180 and 125

feet tall, were the world’s largest standing Buddhas and among the

oldest such representations. But in March 2001, they met their demise at

the hands of the Taliban. Since then, people have been working to preserve

the cultural site and discussing whether or not to rebuild the statues.