Astronomers

have revised the Torino Impact Hazard Scale, which uses

rankings from 0 to 10 to communicate the risk of an asteroid or comet colliding

with Earth. Although scientists still assign scale values via the same method,

the language used to describe some levels has now changed to better inform the

public — and the media — of the risk without unintentionally scaring

people.

Astronomers

have revised the Torino Impact Hazard Scale, which uses

rankings from 0 to 10 to communicate the risk of an asteroid or comet colliding

with Earth. Although scientists still assign scale values via the same method,

the language used to describe some levels has now changed to better inform the

public — and the media — of the risk without unintentionally scaring

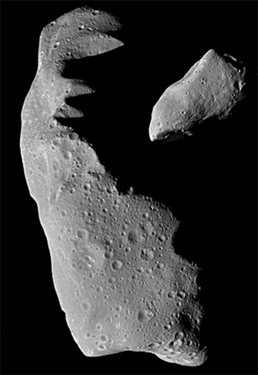

people.More than 100,000 asteroids, such as Gaspra shown at left, lie in a belt between Mars and Jupiter, and about 1,100 of these space objects are at risk of coming close to Earth. Scientists tracking these large asteroids have revised their 10-level threat scale to better communicate the risk to the public. Courtesy of NASA.

Astronomers estimate that there are now about 1,100 large space objects hurtling toward Earth’s neighborhood. Once every 500,000 years or so, one of these Near Earth Objects (NEOs) finds itself on a direct collision course with the planet. Because no such impact has occurred in human history, speculating on whether the planet is due for one anytime soon could be a statistical parlor game, but astronomers are trying to take out the guess work.

Since 1998, NASA’s Spaceguard program has been discovering and tracking NEOs with diameters greater than 1 kilometer — the size at which an impact would be expected to have global effects — with the goal of identifying more than 90 percent by 2008.

“Chances are there is no sizeable threat in the coming century, but it makes sense to survey the sky to make sure,” says Richard P. Binzel, planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge (see Geotimes, January 2004). “If an object were discovered, the best bet would be to launch a mission to try to nudge it off course,” he says, which could take a decade or more to plan.

In 1999, with the number of detections increasing, Binzel introduced a scale at an International Astronomical Union workshop in Torino, Italy, to standardize the way in which astronomers publicly communicate the risk of asteroid close encounters. The Torino Scale has been in use since then, but Binzel and colleagues have seen a need for modification.

“As time went on, we wanted to make sure that we were more clear about what each category meant in terms of how the public should respond,” Binzel says. “In almost all cases, there’s effectively no need for public concern.” For example, levels 2 to 4 were previously described as close encounters “meriting concern” but did not specify by whom. Now they are described as “meriting attention by astronomers.”

Another key change was the addition of language that emphasizes that “the discovery and prediction of asteroids is part of the scientific process and as new data come in, we’re able to refine our answers,” Binzel says. A phrase describing the varying likelihood that “new telescopic observations will lead to re-assignment to Level 0” is now included in categories 1 through 4.

Indeed, that recently happened with asteroid MN4, which on Dec. 23 was given the highest Torino score to date — level 4 — and a 2 percent chance of hitting Earth in 2029 (see Geotimes, March 2005). The announcement garnered media attention that in many cases failed to note the uncertainty surrounding the process. And after further tracking the asteroid’s orbit, astron-omers reclassified it as level 1, with no effective chance of collision. The 400-meter-wide asteroid is now expected to pass within about 23,000 miles of Earth, roughly the same altitude at which geosynchronous satellites orbit.

Although some critics say that making such announcements before final orbits are calculated unnecessarily frightens the public, Binzel says that it is better to keep the public well-informed. “Any time we discover an object, we simply release what information we know when we know it.”

“The revisions in the Torino Scale should go a long way toward assuring the public that while we cannot always immediately rule out Earth impacts for recently discovered near-Earth objects, additional observations will almost certainly allow us to do so,” said Donald K. Yeomans, manager of NASA’s NEO Program Office, in an MIT press release.

With 60 percent of all large NEOs accounted for by 2003, NASA turned its attention to objects less than 1 kilometer across, which are likely to hit Earth about once every thousand years or less. Although these smaller objects would not likely cause global damage, a recent NASA report says that such impacts on land and in the ocean could cause damage regionally.

The search, the report says, could take an additional 7 to 20 years, but would eliminate 90 percent of the risk from smaller objects, and would also probably catch any of the larger objects not yet found by the time the first survey ends in 2008.