Several

significant earthquakes have struck California this week, ranging from 4.9 to

7.2 in magnitude, with two off the coast of Northern California and two in the

Los Angeles basin. Although such a series of events may send some people looking

to the stars' alignment or other explanations for this spate of seismicity,

scientists say that as a whole, the major temblors are mostly unrelated. But

the events on these very separate faults probably interacted with each other

on a regional scale.

Several

significant earthquakes have struck California this week, ranging from 4.9 to

7.2 in magnitude, with two off the coast of Northern California and two in the

Los Angeles basin. Although such a series of events may send some people looking

to the stars' alignment or other explanations for this spate of seismicity,

scientists say that as a whole, the major temblors are mostly unrelated. But

the events on these very separate faults probably interacted with each other

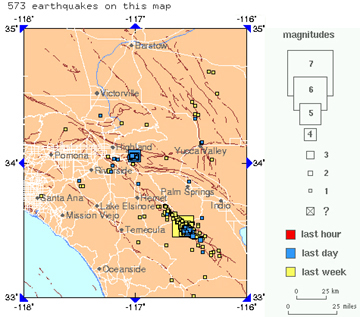

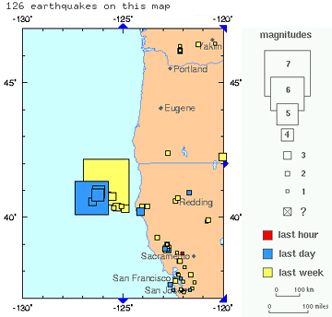

on a regional scale. Regional maps for four major earthquakes show some of their aftershocks and other earthquakes that have occurred in California over the past week. Note the difference in distance scale for each image (earthquake size scales are the same). Earthquakes in the San Andreas fault system (right) may be related to each other, and the largest earthquake on the Gorda plate (below left) probably triggered the subsequent magnitude 6.7 that occurred today. Courtesy of USGS/ANSS.

Seismologists

suggest that the magnitude-6.7 quake that shook the Gorda plate today is probably

an aftershock to the magnitude-7.2 earthquake that sent the entire West Coast

scrambling on Tuesday night after a short-lived tsunami warning (see Geotimes

Web Extra, June 15, 2005). "The Gorda plate has been a very active

site," says Ross Stein, a seismologist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

in Menlo Park, with a magnitude-7 event every 20 years or so. (The last was

a magnitude 7.2 in 1980, he says.) Because of the configuration of the region,

which is a major subduction zone known as the Mendocino Triple Junction, the

Gorda plate is "warped and it's just covered with strike-slip faults,"

Stein says. He says that the relationship between this week's two events is

probably "static stress triggering," where the stress on the faults

has been ratcheted up so that one triggers the other (though he has yet to do

the calculations).

Seismologists

suggest that the magnitude-6.7 quake that shook the Gorda plate today is probably

an aftershock to the magnitude-7.2 earthquake that sent the entire West Coast

scrambling on Tuesday night after a short-lived tsunami warning (see Geotimes

Web Extra, June 15, 2005). "The Gorda plate has been a very active

site," says Ross Stein, a seismologist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

in Menlo Park, with a magnitude-7 event every 20 years or so. (The last was

a magnitude 7.2 in 1980, he says.) Because of the configuration of the region,

which is a major subduction zone known as the Mendocino Triple Junction, the

Gorda plate is "warped and it's just covered with strike-slip faults,"

Stein says. He says that the relationship between this week's two events is

probably "static stress triggering," where the stress on the faults

has been ratcheted up so that one triggers the other (though he has yet to do

the calculations).Susan Hough, a seismologist in the USGS Pasadena office, agrees, and she adds that a magnitude-3.9 earthquake in the nearby Geysers geothermal field was also probably triggered by that first major earthquake on the Gorda Plate. That field is several hundred kilometers away from the epicenter.

Farther south, two earthquakes that struck in Southern California this week were about 80 kilometers (50 miles) away from each other. A magnitude-5.6 shock on the San Jacinto fault, near Anza, Calif., has had a zone of aftershocks that has extended farther than might be expected, Stein says, and he is anxious to see the stress regime to see what the cause may be. The earthquake occurred in what is known as the "Anza gap," a relatively inactive part of the San Jacinto system, which is otherwise extremely active.

On Thursday, June 16, a magnitude-4.9 earthquake hit Yucaipa in the San Andreas Fault system. Looking at the history of this segment of the fault, it has a 1-in-3 projected probability of rupturing in the next 30 years, according to work by Ray Weldon of the University of Oregon in Eugene and his co-authors. The prehistoric seismic record shows large earthquakes around magnitude 8 or more occurred every 200 years or so on this segment — and the last occurred in 1812, at a magnitude 7.5 or so, Stein says.

"Any way you look at it, this is an area that is coming due," he says. And the combination of a highly stressed portion of the fault with a highly populated region is further cause for concern, he says, as the region — known as the Inland Empire, near San Bernardino — is a dense part of the Los Angeles basin. Normally, "a 5.2 doesn't threaten anyone," Stein says, but here, "we need to be concerned and it should be closely watched, and it is being closely watched."

Stein recently co-authored a paper with Shinji Toda of the Active Fault Research Center, in Tsukuba, Japan, and others that models and forecasts activity on the San Andreas Fault for the near future. Their 10-year forecast of magnitude-5 earthquakes and bigger for the area covers the region of the Landers earthquake, a magnitude 7.4 that occurred in 1992, which includes a high-risk segment where the Yucaipa event occurred. Hitting the mark somewhat is "encouraging," Stein says, "but that's all you can say."

Stein says that the Yucaipa earthquake may be another kind of aftershock of the Anza event, but that the system is "a little more feebly connected, and far enough away that the stresses probably aren't that large."

Hough, on the other hand, is more certain that the two are related, and that the Anza event probably triggered the Yucaipa earthquake. "I think it's very realistic," she says, when considering the patterns for Southern California over the past few years. The same thing happened with the Parkfield earthquake last year, which triggered a magnitude-5 earthquake in nearby Bakersfield a day later, Hough says.

That nearby triggering for both of the big earthquakes that have happened this week — the magnitude 7.2 on the Gorda in the north and the magnitude 5.6 near Anza in the south — may be a bit misleading, Hough says. The two earthquakes and their after-effects "can conspire to convince you that something dire is happening in California," she says, "because of the cascading events." But it is more a normal state of affairs, in some ways, as California experiences magnitude-5.2 events "every couple months on average."

Still, Hough, Stein and other seismologists are watching carefully to see what happens, while being careful in their predictions. "One sort of learns to be careful with predictions" of a big one on the San Andreas Fault, Hough says. "It may be it could happen tomorrow, but we haven't seen anything definitive."

Naomi Lubick