|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

||||||||

|

It's Time to Know the Planet's Mineral Resources |

| “Industrialization is central

to economic development and improved prospects for

human well-being. … A substantial share of industrial growth in developing

countries revolves around the transformation of raw materials into industrial

materials.”

-— from

World Resources by the World Resources Institute and Others, 1998-1999

|

Who Will Use A Global Mineral Assessment? |

The world’s population is increasing. More people worldwide want to improve their living standards. Both of these trends are fueling an increasing global demand for mineral resources.

The good news is that no global shortages of nonfuel mineral resources are expected in the near future. However, a growing number and variety of real and perceived obstacles have begun to reduce the availability of these resources. Mining must compete for space with other land uses, such as growing domestic space. Mining can have limited economic and social benefits, especially to populations in the developing world. Many people are reluctant to approve mining operations because they perceive that our culture of disposability and convenience wastes resources and unnecessarily pollutes. Mining can adversely affect the environment. Often, people do not trust companies or government officials when they promise that those effects can be prevented or permanently mitigated.

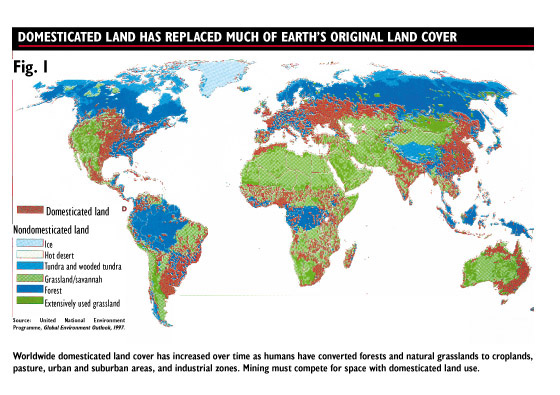

The two obstacles that most strongly affect minerals development are competing land uses and growing concerns over the possible environmental degradation associated with mining. Domesticated land has replaced much of Earth’s original land cover, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Unanticipated and therefore unplanned growth in mineral exploration

and development, especially in sensitive ecosystems, can further fragment

and destroy habitats required for key plant and animal communities, thereby

degrading and threatening overall ecosystem health. Increasingly, human

populations and their activities, such as mining, “are disturbing species

and their habitats, disrupting natural ecological processes, and even changing

climate patterns on a global scale,” according to a 1998 report by the

President’s Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST). A

1998 article in Science by biologist Jane Lubchenco echoes this

concern: “We are modifying physical, chemical and biological systems in

new ways, at faster rates, and over larger spatial scales than ever recorded

on Earth.”

A troubled image

What is the one thing the average citizen is most likely to have heard and believe about mining?

Is it that we are running out of nonfuel minerals and we are all going to die? Probably not. Global supplies of nonfuel minerals are adequate now.

Is it that mining is an important part of the global economy? Again, probably not. By some measures, the mining sector appears to be a small player. Pierre Lassonde, CEO of Franco-Nevada Mining, pointed out in the July 2000 Mining Engineering that “Adding together all of the global gold, copper, aluminum, nickel, zinc and diamond producers represents a business with a total market capitalization of about U.S. $200 billion. Some individual companies like Microsoft and Cisco Systems are valued at more than U.S. $400 billion.”

Does the average person think that mining companies are having terrific environmental successes? No, probably not. Environmental successes in the mining sector seldom make headline news.

Is it that mining causes environmental and sometimes social disasters? Bingo.

The negative image of mining has reached the point where leaders of mining companies are promoting benefits to the mining industry of owning up to past shortcomings and embracing environmental and social responsibilities for sustainable development. Patrick James, CEO of Rio Algom Ltd., was among the first to urge that mining, like other forms of development, must contribute not only economic value to stakeholders, but also environmental and social value. In the June 1999 Mining Engineering, he also observed that “as an industry, we will gradually find ourselves unable to operate anywhere if we are incapable or reluctant to effectively combine economic, environmental and social goals everywhere we do business” (see also James’ article in the July 2000 Geotimes).

In summarizing the major challenges the mining industry faces, Sir Robert Wilson, executive chairman of Rio Tinto, the world’s largest mining company, writes in the June 2000 Mining Engineering that mining finds itself in increasing disfavor in the United States, Canada, Europe and many other parts of the world. He adds that industry’s traditional responses — to say that criticisms are ill-founded, to remind critics that they depend on mineral products, and to engage in education, advertising and public relations campaigns — have all been to little or no avail. Mining’s reputation continues to deteriorate, he concludes. Sir Robert urges the mining industry to change its dialog with stakeholders, especially with nongovernment organizations, and supports a new global mining initiative to seek “independent analysis of issues that will determine the future of mining, and that these issues are social and environmental as well as economic.”

A global assessment of mineral resources would be an important component of such an analysis.

Finding space for mining

Informed planning and decisions about biological sustainability and resource development require a long-term perspective and an integrated approach to worldwide land-use, resource and environmental management. This approach requires unbiased information on the global distribution of identified and, especially, undiscovered resources; on the economic, social and political factors influencing their development; and on the environmental consequences of, and requirements for, using them.

The world’s present approach to land and resource planning is piecemeal and haphazard. Sources of future mineral supplies are rapidly becoming more restricted while land and resource planning is inadequate to assure that mineral resources are available with the least environmental effect. The United States is the only country that has ever conducted a national assessment of the regional locations and amounts of its remaining undiscovered nonfuel mineral resources. Decisions about land withdrawals from mineral entry are not being made with a global perspective. Environmental planning is also haphazard, happening by default rather than by plan.

Developing minerals is prohibited, or may soon be prohibited, in Antarctica and the Arctic Islands; in national and international parks, wildlife preserves and wilderness areas; in tropical rainforests, temperate old-growth forests and alpine and desert regions; and in many other sensitive or endangered habitats, ecosystems, scenic vistas and roadless areas. As countries grow and develop, mining also becomes increasingly unwelcome at home.

Highly industrialized societies have a responsibility to help other countries collect and provide information and assist in planning global mineral development and ecosystem sustainability. These economies use tremendous amounts of minerals-derived materials per capita: 45 to 85 metric tons per person per year, according to a 1998 study by the World Resources Institute and others. Using these materials requires moving or processing huge amounts of rock and other natural resources not actually used in the final product. As much as 50 to 75 percent of this hidden flow of materials, and associated environmental effects, often takes place in other countries.

Consequently, the United States and other highly industrialized countries should help initiate and participate in an international assessment of the probable regional locations, amounts and types of the world’s undiscovered, nonfuel mineral resources. This assessment should be coupled with assessments of sensitive ecosystems and habitats so that mineral development can be encouraged in areas best able to sustain the environmental effects of mining and mineral processing, and can be discouraged or carefully managed in sensitive areas.

We may find that most of our future resources of some minerals can only

be found in areas where maintaining ecosystem health and sustainability

is difficult. In this case, international cooperation will be even more

crucial so that we can optimize materials flows and recycling of materials

we derive from these minerals; promote research into alternative materials

and technologies to replace these minerals or minimize their use; and develop

advanced mitigation techniques for exploration, mining and processing.

“An electorate that does not understand the natural world or

the nature of the tradeoffs that must be made in managing it wisely and

sustainably cannot make informed decisions,” according to a 1998 PCAST

report.

The challenges of assessment

In response to growing concern about the global sustainability of nonfuel mineral production and environmental quality, and the simultaneous increase in demand for global mineral-resource information, this year, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) will complete a study of the feasibility of assessing and predicting where and how much undiscovered, nonfuel mineral resources remain on the planet. Is it possible, practical or useful to conduct such an assessment at a global scale? The study evaluates how many people from what countries and organizations and with what kinds of expertise would be needed to do such an assessment, and how they might best organize themselves.

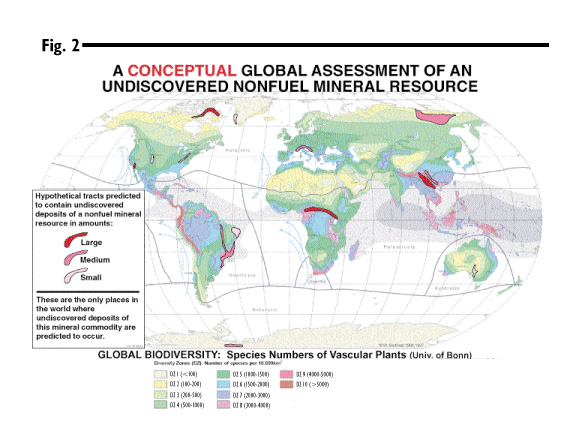

In 1996, the USGS Minerals Team published its first assessment of known geologic types of undiscovered resources of gold, silver, copper, lead and zinc in the United States (see Fig. 2). We are determining whether the methods used for this assessment are practical for a global assessment.

The

preliminary results of our feasibility study indicate that a global mineral

assessment is possible, useful and needed. The USGS plans to begin organizing

and participating in an international global assessment of undiscovered

copper, platinum-group metals and potassium in October 2001. Copper was

chosen because it is important in electronics and other industrial and

residential applications, it is globally distributed, and its predictive

geologic occurrence and grade-tonnage models are well defined. We chose

the platinum-group metals because they have critical applications as automobile

catalysts required to clean our air, because their supply is limited and

extracting them is expensive, because only a small number of known deposits

are known globally, and because the grade-tonnage models for these mineral

deposits need to be better defined for increased use. Potash was chosen

because it is one of the three indispensable fertilizer minerals without

which we could not produce enough food to feed most of the world, and because

its predictive models need additional testing. Each time we undertake new

mineral resource assessments, we seek to include research that will test

and improve our data, geologic models and understanding of the fundamental

processes of mineral formation.

The

preliminary results of our feasibility study indicate that a global mineral

assessment is possible, useful and needed. The USGS plans to begin organizing

and participating in an international global assessment of undiscovered

copper, platinum-group metals and potassium in October 2001. Copper was

chosen because it is important in electronics and other industrial and

residential applications, it is globally distributed, and its predictive

geologic occurrence and grade-tonnage models are well defined. We chose

the platinum-group metals because they have critical applications as automobile

catalysts required to clean our air, because their supply is limited and

extracting them is expensive, because only a small number of known deposits

are known globally, and because the grade-tonnage models for these mineral

deposits need to be better defined for increased use. Potash was chosen

because it is one of the three indispensable fertilizer minerals without

which we could not produce enough food to feed most of the world, and because

its predictive models need additional testing. Each time we undertake new

mineral resource assessments, we seek to include research that will test

and improve our data, geologic models and understanding of the fundamental

processes of mineral formation.

We are investigating using three types of data: maps of the locations, sizes and geologic types of known mineral deposits and occurrences; maps of regional geologic terranes and tracts according to the geologic types of undiscovered mineral deposits they could contain; and as much information as possible about mineral exploration history. Much of the exploration information resides in the mining industry’s corporate memory and files. The private sector’s participation in all stages of an assessment is important.

Not just for exploration

The topics that follow are only starting points for discussions of many

possible uses for a global assessment of undiscovered mineral resources.

A global assessment could help us to recognize, discuss, manage and minimize

or prevent environmental tradeoffs and effects associated with mineral

exploration and mining.

Biodiversity and sensitive habitats. What are some examples of the potential consequences of developing the undiscovered mineral resources illustrated conceptually in Fig. 2? Mining at high latitudes, where biodiversity is low, probably will have a smaller impact on biodiversity than mining in low latitudes, where biodiversity is much greater. Moreover, people would be less likely and less able to stay in the harsh climate of the high latitudes after mining had ceased. Without mining, many of these areas have little or no employment and infrastructure and, unlike in the tropics, subsistence farming is difficult or impossible.

On the other hand, disturbed ecosystems would likely require a longer time to recover in these severe climates. Infrastructure development that follows mining into remote regions can disrupt a sensitive habitat. Some of the undiscovered resources in Southeast Asia, for example, occur in endangered tiger habitat. Discovering and developing kuroko-type massive sulfide deposits in the Sierran foothills of central California could potentially affect endangered species habitat and vulnerable plant communities delineated by the USGS Gap Analysis Program. World tin resources in differing geologic settings have a high spatial correlation with the distribution of biodiversity “hotspots” defined by a 1999 Conservation International study.

Land Use. Developing infrastructure can disturb and fragment habitats and, as a result, cause species extinction. Perhaps some steps could be taken to encourage mineral exploration and development in regions where infrastructure already exists in order to reduce habitat fragmentation. Maps and other information showing the types and density of infrastructure development and other land uses would be important ancillary databases for using a global mineral assessment. Amy Rosenfeld Sweeting and Andrea P. Clark point out in Lightening the Lode, published by Conservation International, that ideally, mineral exploration programs would only disturb areas that have a high probability of containing an economic deposit. Attempting to identify such areas is an important objective of the global assessment.

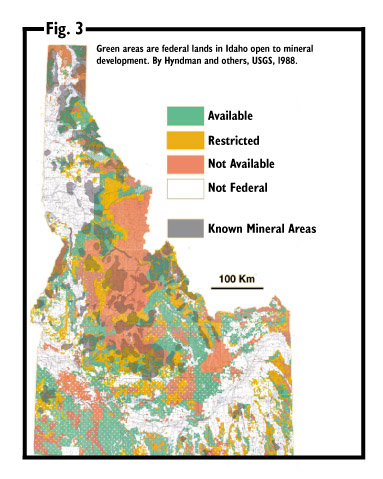

What

areas of the world already are off limits to mineral exploration and development?

We don’t know, but maps showing such areas would be a useful product of

a global mineral assessment. The colored areas of federal land in Idaho

shown in Fig. 3 were once open to mineral development. Now only the green

areas are open. Who believes the green areas have increased in number or

size since 1988, when this map was published?

What

areas of the world already are off limits to mineral exploration and development?

We don’t know, but maps showing such areas would be a useful product of

a global mineral assessment. The colored areas of federal land in Idaho

shown in Fig. 3 were once open to mineral development. Now only the green

areas are open. Who believes the green areas have increased in number or

size since 1988, when this map was published?

Water resources and quality. The boundaries of major drainage basins cross governmental jurisdictions and many are international. A global mineral assessment could help identify future mineral resources in regions with adequate water supplies and with hydrologic and geologic characteristics best able to maintain water quantity and quality during and after mineral development.

Such an assessment also could highlight combinations of undiscovered mineral resource types, topographic settings, and climatic conditions least likely to cause environmental difficulties. For example, carbonate-hosted mineral deposits containing small amounts of iron sulfide and occurring in areas of low relief in climates having moderate to low rainfall often can be mined with less chance of producing toxic waters laden with acids and heavy metals.

The final analysis

Individual countries are no longer completely free to develop their natural resources at the expense, real or perceived, of social and environmental quality — including clean air and water, endangered species, biodiversity, the global climate and the ozone layer. National decisions about trade, including those made in the United States, often must follow laws requiring that associated environmental consequences be considered. Global environmental and trade agreements can be linked in ways restricting natural resource development. International funding agencies such as the World Bank and United Nations may withhold funding from projects seen as potential threats to environmental quality. Boycotts by consumers and national governments have been used effectively to influence, restrict and even stop natural resource development. The charter for the World Trade Organization allows environmentalist import bans so long as the reason for them is not disguised protectionism.

International “free trade” no longer includes many resources such as whales, ivory, seals, furs, eagle feathers and other parts of endangered species, to name only a few. Our tuna no longer is flavored with dolphin, nor is our shrimp flavored with turtle. International pressure to protect the environment in all its aspects will only grow with time. Without the information that a global mineral resource assessment could provide, we may unknowingly foreclose future mineral supply options — options that might reduce environmental degradation, improve economic benefits and enhance social values.

The authors work at the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Va. E-mail: jbriskey@usgs.gov

Link to the second part of this feature:

"Who Will Use A Global Mineral Assessment?"

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |