This environment,

says Whitey Hagadorn of the California Institute of Technology, was the perfect

setting for some large jellyfish to leave their legacy. He says the Cambrian

sediment trapped hordes of jellyfish, some up to a meter across, preserving

their shape and form. In the February issue of Geology, Hagadorn, Robert

Dott and Dan Damrow describe how they think these jellyfish remained so well

preserved on Wisconsin’s Upper Cambrian shoreline.

This environment,

says Whitey Hagadorn of the California Institute of Technology, was the perfect

setting for some large jellyfish to leave their legacy. He says the Cambrian

sediment trapped hordes of jellyfish, some up to a meter across, preserving

their shape and form. In the February issue of Geology, Hagadorn, Robert

Dott and Dan Damrow describe how they think these jellyfish remained so well

preserved on Wisconsin’s Upper Cambrian shoreline. “These are the largest jellyfish in the fossil record and it’s one of only two jellyfish deposits in the entire fossil record, which is rather ironic because they’re both upper Cambrian in age,” Hagadorn says. The other fossil site is in New Brunswick.

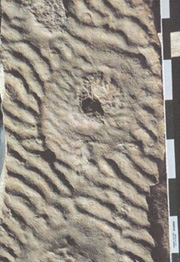

The bottom of a slab from Upper Cambrian Mount Simon-Wonewoc Sandstone in central Wisconsin that contains what are believed to be jellyfish impressions. The larger rippled ring structures are sand deposited around the jellyfish and then rippled by a storm event. Each scale bar is 10 centimeters (about 4 inches). Courtesy of Whitey Hagadorn.

These fossils are unusual, Hagadorn explains, because of their large size and high abundance, as well as their exceptional preservation in a medium- to coarse-grained sand. “When people find a T-rex, that doesn’t excite me that much, because a T-rex has bones and teeth. It is really easy to fossilize,” Hagadorn says. But it is much more difficult to fossilize a jellyfish, because it lacks hard parts. “Something is there we don’t understand,” he says.

Hagadorn and his colleagues looked at present-day shores to help them identify the factors that led to the preservation of these fossils. Importantly, Hagadorn says, in the Upper Cambrian, few scavengers were around eating the jellyfish carcasses. “If jellyfish are washed up on the beach today, they are very likely going to be scavenged by terrestrial organisms.” Similarly, few animals were turning up sediments. “Think about going to a modern beach today and seeing sand crabs burrowing through the sand at the shoreline,” he says.

Says Hagadorn, the jellyfish also had to remain underneath a large volume of sediment. Jellyfish could swim into the sandy tropical embayments to migrate, prey on other organisms or reproduce. A strong storm event could then have trapped them. Hagadorn and his colleagues found at least seven different layers of jellyfish fossils over a couple of meters of sediment. Because there is no unconformity between the layers, Hagadorn says, the stranding events could represent a period of time anywhere from one season to a hundred thousand years.

These fossil findings have George Stanley asking a lot of questions. An invertebrate paleontologist at the University of Montana, Stanley studies cnidarians, a group of animals that includes coral and jellyfish. “We know less than 1 percent about all organisms that ever lived. And of that less than 1 percent, most are hard shelled,” he says. Therefore, the abundance of these large Cambrian fossils of soft-bodied creatures fascinates Stanley. He says Hagadorn’s study is only a small part of the story of this rare preservation. “The real questions to me are what is behind the fossils and what they might tell us about evolution,” Stanley says. Hagadorn hopes to answer these questions by using his findings to better explore the Cambrian marine community, as well as the mechanisms for soft-bodied organism preservation.

The fossils are in the Upper Cambrian Mount Simon-Wonewoc Sandstone in central Wisconsin, well known for the preservation of the tire-track-sized trails Climactichnites. About four years ago, Damrow, a commercial fossil dealer, was collecting these trace fossils and sent Hagadorn photographs from the deposit. Several of the photographs had large disc-shaped structures on them that looked like jellyfish impressions. And that piqued Hagadorn’s curiosity.

At first, Hagadorn says, they could not identify the fossils. “You can get a lot of disc-shaped structures produced by other processes. There are a million ways to produce a round mark on a rock,” he says. But after meeting with Bob Dott in Wisconsin and analyzing the fossils at the site and at Caltech, Hagadorn concluded the fossils were indeed medusae, or jellyfish. “There’s just no other way to produce these structures unless you have a soft-bodied spheroidal bag, or jellyfish, stranded on a shoreline.”

But some paleontologists remain skeptical. Simon Conway Morris, a paleontologist at the University of Cambridge who studies the Cambrian explosion, says that while the fossils look like jellyfish, other possibilities remain, including a connection to the Climactichnites, which he describes as “extremely spectacular trace fossils made by something akin to a gigantic slug.” The fossils, he says, although this is unlikely, could be some sort of egg case. Everything related to the fossils is still speculative, Morris stresses.

Hagadorn, Dott and Damrow address the possible Climactichnites connection in their paper, and “their explanation is as good as anybody can manage at the moment. It’s a very sort of curious find,” Morris says. “As exciting as the results are, they do actually pose additional questions, which are clearly going to open new lines of inquiry.” And that, Morris says, is what science is all about.

Lisa M. Pinsker

A version of this story first appeared as a Web Extra on Jan. 30, 2002.