With

its majestic mountains, the Wasatch Range seems the perfect site for last month’s

Olympic competitions in skiing, snowboarding and bobsledding. But beneath the

wintry landscape, rocks are slowly grinding, lifting the mountains and creating

the potential for an earthquake. “Here in our Wasatch front urban corridor,

the major threat is posed by the Wasatch fault, which is the longest active

normal fault in North America,” says Walter Arabasz, director of the University

of Utah Seismograph Stations.

With

its majestic mountains, the Wasatch Range seems the perfect site for last month’s

Olympic competitions in skiing, snowboarding and bobsledding. But beneath the

wintry landscape, rocks are slowly grinding, lifting the mountains and creating

the potential for an earthquake. “Here in our Wasatch front urban corridor,

the major threat is posed by the Wasatch fault, which is the longest active

normal fault in North America,” says Walter Arabasz, director of the University

of Utah Seismograph Stations. And that is where Arabasz and his team of earthquake watchers came into play in the Olympic Games. They partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey to put a real-time earthquake information system in place in time for the Olympics. “It’s a convergence of needing to have rapid earthquake information available during the Olympic time-frame, but also the building of an Advanced National Seismic System to modernize earthquake monitoring in the United States,” Arabasz says.

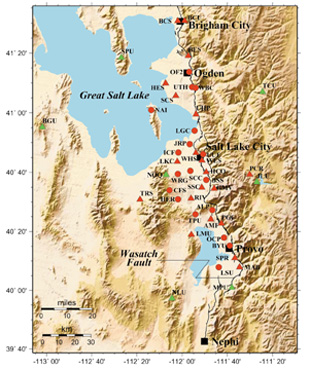

A Shakemap relies on a seismograph network of strong motion sensors that continuously record seismic activity to upload to a telecommunication system. In Utah, 45 sensors lie within and surrounding the urbanized area. In the picture, red circles show strong motion sensors installed in 2000. Red triangles were installed in 2001. The green triangles represent sensors with broadband.

Authorized by Congress in 2000, the Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS) calls for installing more than 6,000 seismic sensors to monitor earthquakes in 26 U.S. metropolitan areas. ANSS is only about 5 percent complete now, but Salt Lake City was one of the lucky few cities to get a head start on the project, Arabasz says. The seismic network features a Shakemap — a rapidly generated computer map that uploads directly to the program’s Web site, where anyone, including emergency managers and earthquake scientists, can view the results.

Lisa M. Pinsker

For the past decade,

sinkholes and wide, shallow subsidence features have become major problems along

the shores of the Dead Sea, in Israel and Jordan. Geoscientists from the Geological

Survey of Israel, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Tel Aviv University

and the Technion-Israel Institute are using InSAR (interferometric synthetic

aperture radar) to identify and characterize areas of instability and to measure

rates of subsidence along the Dead Sea shores, on the Lisan Peninsula. Led by

Gidon Baer of the Geological Survey of Israel, the team published their results

in the January GSA Bulletin.

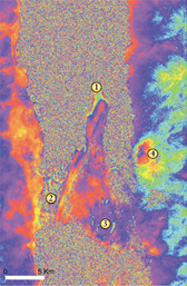

For the past decade,

sinkholes and wide, shallow subsidence features have become major problems along

the shores of the Dead Sea, in Israel and Jordan. Geoscientists from the Geological

Survey of Israel, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Tel Aviv University

and the Technion-Israel Institute are using InSAR (interferometric synthetic

aperture radar) to identify and characterize areas of instability and to measure

rates of subsidence along the Dead Sea shores, on the Lisan Peninsula. Led by

Gidon Baer of the Geological Survey of Israel, the team published their results

in the January GSA Bulletin.