Geotimes

Untitled Document

Web Extra

Monday, Mar. 28, 2005

Sumatra

seismic risk

On the heels of the December 2004 tsunami that devastated Indonesia and resulted

in the deaths of almost 300,000 people, scientists are taking a closer look

at the seismic and tsunami risk of various faults around the world. Recent research

indicates that Indonesia, as well as other regions like the Caribbean, could

experience more earthquake and tsunami activity in the near future.

John McCloskey and colleagues from the University of Ulster, United Kingdom,

calculated the stress on the Sunda trench subduction zone and Sumatra fault,

caused by recent seismic activity. Their results, published in the March 17

Nature, indicate an increase in the stress on both of the fault zones

due to the movement of the initial quake in December.

The segment

of the Sunda trench immediately south of the December earthquake has been locked

by friction since 1866, says Ross Stein with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo

Park, Calif., who is not affiliated with the study. Now that the Dec. 26 shock

has stressed the segment, it should come as no surprise if a large magnitude

temblor were to strike this segment soon, he says.

The segment

of the Sunda trench immediately south of the December earthquake has been locked

by friction since 1866, says Ross Stein with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo

Park, Calif., who is not affiliated with the study. Now that the Dec. 26 shock

has stressed the segment, it should come as no surprise if a large magnitude

temblor were to strike this segment soon, he says.

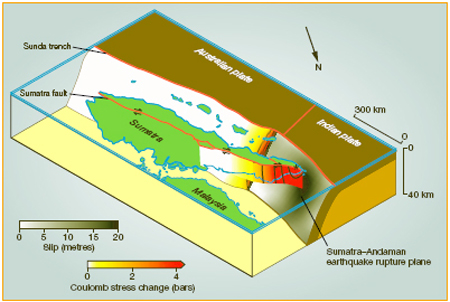

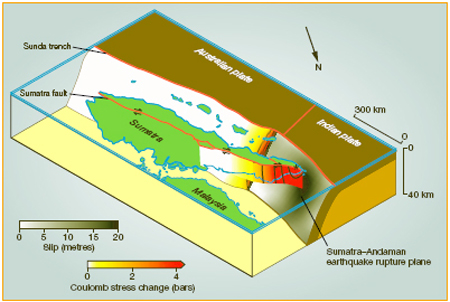

This block diagram represents where the

Sumatran plate is subducted beneath the Indian plate. On the right, the star

indicates the rupture plane just below the city of Banda Aceh, where the worst

devastation was felt. The grey-scale values (on the Indian plate) depict the

amount of slip in meters, with the largest amount at the rupture plane. The

color-scale (ranging from yellow to red) indicates the amount of additional

stress applied to the Sunda trench subduction zone and the Sumatra fault, where

the next earthquakes will likely occur, due to the original rupture. Image courtesy

of Nature.

If an earthquake of magnitude 7 or higher were to hit the Sunda trench fault,

it would cause another tsunami because of its location underwater, as well as

its history of tsunami generation in 1833 and 1861, wrote the authors. A more

immediate threat, they said, is the possibility of an earthquake on the Sumatra

fault, which is not underwater and therefore poses less of a tsunami risk.

John Vidale, the interim director of UCLA's Institute of Geophysics and Planetary

Physics, says that the model confirms what seismologists would naturally guess:

that the whole neighborhood near the ruptured area is at risk of experiencing

further motion. However, he says, it's useful to identify which faults pose

the greatest risk, and the authors have been able to quantify the amount of

stress on those particularly dangerous areas. "The risk [of a large earthquake]

is relatively minor," he says, "but it's greater than last year."

Predicting where movement in the crust will happen next is "guess work"

because seismologists are unsure of the crust/mantle response, Vidale says.

"Rupture models are not something you can trust in detail." If the

response of the underlying crust is viscous, reacting like syrup rather than

a brittle twig, there might be additional motion, causing stress on some faults

and alleviating stress on others, Vidale says. "The whole process is pretty

mysterious."

"What we need now," Stein says, "are networks of seismometers,"

not only for Indonesia, but also for the Caribbean. Indeed, says Nancy Grindlay,

a marine geologist with the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, "the

biggest worry is along the North American and Caribbean plate boundary, which

is really analogous to the Sumatran boundary zone." The zone is a strike-slip

boundary and motion along it could rupture the seafloor, pushing the ocean water

and generating a tsunami, she says.

Grindlay and colleagues published a seismic study of the Caribbean islands

based on 500 years of historical records of earthquake and tsunami disasters,

in the March 22 Eos, and say that underwater landslides are also a major

concern in the area. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission has approved

a tsunami warning system project proposal, and plans to meet throughout the

spring and summer to discuss implementation strategies for the Caribbean.

However, Vidale says that even if a warning system were in place, "it

wouldn't have helped the people of Sumatra too much," because the rupture

occurred so close to the mainland and there was no time to issue a warning before

the wave hit the shore. Seismologists did not have a consensus that there would

be an earthquake in the area because quakes are unlikely on subduction zones

such as the one found in Sumatra, he says. "It was low on the priority

list," Vidale, says. "Other places are more prone — we were just

unlucky."

Laura Stafford

Links:

Nature

homepage

Back to top

Untitled Document

The segment

of the Sunda trench immediately south of the December earthquake has been locked

by friction since 1866, says Ross Stein with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo

Park, Calif., who is not affiliated with the study. Now that the Dec. 26 shock

has stressed the segment, it should come as no surprise if a large magnitude

temblor were to strike this segment soon, he says.

The segment

of the Sunda trench immediately south of the December earthquake has been locked

by friction since 1866, says Ross Stein with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo

Park, Calif., who is not affiliated with the study. Now that the Dec. 26 shock

has stressed the segment, it should come as no surprise if a large magnitude

temblor were to strike this segment soon, he says.