Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers

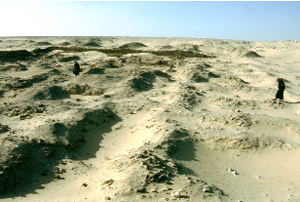

Eva Panagiotakopulu

went to the ancient city of Amarna, Egypt, to study how people lived 3,500 years

ago through fossilized insect remains. Unlike the nice clean city portrayed in

many reconstructions, the city, she discovered, was infested with bedbugs, fleas

and flies. And what she found in the insects was also a surprise: plague. On further

inspection, Panagiotakopulu began to think that perhaps the plague did not originate

in Central Asia, as has long been believed: Perhaps it began in Egypt.

Eva Panagiotakopulu

went to the ancient city of Amarna, Egypt, to study how people lived 3,500 years

ago through fossilized insect remains. Unlike the nice clean city portrayed in

many reconstructions, the city, she discovered, was infested with bedbugs, fleas

and flies. And what she found in the insects was also a surprise: plague. On further

inspection, Panagiotakopulu began to think that perhaps the plague did not originate

in Central Asia, as has long been believed: Perhaps it began in Egypt. |

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |