It may have

seemed like an unlucky break at the time, but when researchers had to slice

a Tyrannosaurus rex femur in half to get it out of the field, they found

something completely unexpected. After some initial cleaning, paleobiologist

Mary Schweitzer at North Carolina State University in Raleigh and her co-workers

found that the T. rex bone still contained what looks like the original

structure of blood vessels and other soft tissues. This is the first time that

such tissues have been found so well-preserved.

It may have

seemed like an unlucky break at the time, but when researchers had to slice

a Tyrannosaurus rex femur in half to get it out of the field, they found

something completely unexpected. After some initial cleaning, paleobiologist

Mary Schweitzer at North Carolina State University in Raleigh and her co-workers

found that the T. rex bone still contained what looks like the original

structure of blood vessels and other soft tissues. This is the first time that

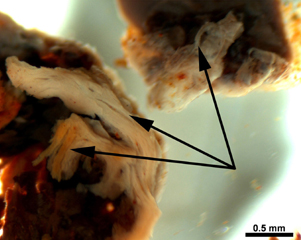

such tissues have been found so well-preserved.Paleontologists have discovered a Tyrannosaurus rex bone that contains what looks like the original structure of blood vessels and other soft tissues, the first such finding ever. Here, arrows point to regions of the bone that look fibrous.

After finding a T. rex specimen at a remote field site in the Hell Creek Formation in Wyoming, members of a field team led by Jack Horner, of the Museum of the Rockies at Montana State University in Bozeman, encased it for removal by helicopter. But the piece was too heavy and had to be cut in half. Back in the lab, scientists set the pieces of bone containing what looked like soft tissues aside for Schweitzer, who worked with Horner’s team before moving to North Carolina last year.

Images of the bone pieces published in the March 25 Science show tiny “dots” that look similar to blood cells, among other interesting visible characteristics. The tissues also remain surprisingly flexible. “They sure look like cells and soft tissue matrix,” Schweitzer says. “It’s hard to imagine mineral replication that is flexible and still transparent.”

“There’s a subtle gradation in the way you can preserve fossils,” says Matt Carrano, curator of Dinosauria at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Typically, minerals completely replace all the “original” materials or structures in a dead animal, in order to create a fossil, retaining only the shape; even soft tissue preservation tends to be limited to skin impressions or other such secondary forms.

The astonishing findings have fueled discussion on whether DNA fragments or even protein may have survived intact during their 70-million-year entombment. “Nobody thinks this is possible, including me,” Schweitzer says, and “we have to be extra, extra careful about it,” when determining whether the structures are original or not. If they exist in the sample, DNA fragments or proteins could give detailed information on the genetic code of T. rex or details of the animal’s metabolism, and the possible answer to the warm-blooded/cold-blooded debate.

Derek Briggs, a paleobiologist at Yale University and an expert on fossilization, says that most likely the team will find “not much more than traces of protein, if indeed they’ve even got protein,” and that no DNA could survive that long. Routine archaeological investigations can analyze DNA up to about 100,000 years old, Briggs says.

The preservation itself is “extraordinary” and “undoubtedly a very spectacular discovery,” Briggs says. The “rigorous” comparative work the team reports in supplementary material supporting the Science publication shows that other fossils may contain similarly preserved soft tissues, he says. How the tissues survived this long remains unknown.