Geotimes

Untitled Document

Web Extra

Thursday, May 5, 2005

Heat imbalance portends problems

Results

from a new assessment show that Earth is absorbing more energy than it releases

into space. With implications for climate change, researchers say the study

points to future warming with consequences for ice sheets and sea level.

Results

from a new assessment show that Earth is absorbing more energy than it releases

into space. With implications for climate change, researchers say the study

points to future warming with consequences for ice sheets and sea level.

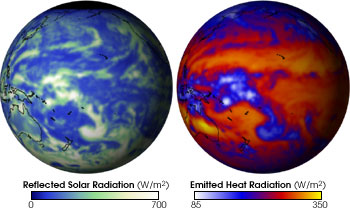

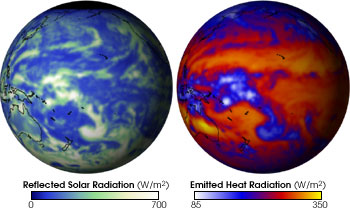

Satellite measurements from CERES show how much solar radiation Earth reflected

(left) and how much heat it emitted (right) on January 1, 2002. The bright spots

are thick clouds that both reflect heat from the sun and trap it on Earth's

surface. New research shows that more heat is being trapped than emitted, unbalancing

the planet's heat ledger. Image courtesy of NASA.

A team of scientists led by James Hansen of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space

Studies (GISS) has run the center's global climate model through a variety of

scenarios, using observations of ocean heat changes over the past decade to

check their conclusions. Published in Science Express on April 28, they

show that the planet takes up around 0.85 watts per square meter more than it

gives off, absorbing heat from the sun that is then trapped by greenhouse gases,

aerosols and other such "forcings," while only a small portion of

the heat escapes. The imbalance in the planet's heat equation is a "smoking

gun" for increased global warming, the researchers say.

Using climate forcings of human-made greenhouse gases and aerosols, along with

other factors, the model shows that the future imbalance to the climate system

will likely come from a lag in ocean temperature shifts. How long it takes to

transfer heat from the ocean's surface to its deep layers will determine how

fast the climate changes.

"The large energy imbalance that we have found implies that global temperature

responds slowly to forcing agents, with much of the response lagging several

decades behind," Hansen said in a press release. The current feedback to

the system "clearly is positive and will lead to additional warming."

The researchers suggest that with additional warming still "in the pipeline,"

policy-makers should find ways to pull the amount of greenhouse gases and aerosols

out of the atmosphere that would match the imbalance in heat absorption in order

to avoid future warming — essentially trying to prevent trapping more heat

to counterbalance the heat that will be released from the oceans later.

The team also forecasts accelerated ice-sheet melting, which could lead to a

10-year sea-level rise of 1.6 centimeters. Continued measurements of ocean heat

storage are necessary, they write, to confirm whether their model is correct

regarding both its sensitivity to climate forcing and the amount of climate

forcing calculated to be occurring.

This study is one of many tests of major climate models from research groups

around the world, which are being prepared for the fourth assessment report

for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, says Gerald Meehl of the

National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo. Meehl calls

the results "consistent" with past and current tests of global climate

models that have coupled ocean-atmosphere dynamics, including that which he

published with co-workers on the NCAR model in Science on March 15. "Even

if the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere had been stabilized

in the year 2000, we are already committed to further global warming of about

another half degree," they wrote, and to substantial sea-level rise, "caused

by thermal expansion [of the oceans] by the end of the 21st century."

Still, the implications from Hansen's team's results are different. "The

ice sheets are what [they are] most concerned about," Meehl says. "Nobody

quite knows these ice sheet mechanisms." Meehl points to the breakup of

the Larsen B Ice Shelf in the Antarctic, which "shattered in a matter of

weeks," he says. "Then the glaciers surged — and are still surging,"

according to research published in the Geophysical Research Letters last

month, signifying increasing temperatures and potentially increasing glacial

inputs into the ocean.

"We're using [the models] as tools to understand what's going on,"

Meehl says. But despite potential problems with those tools, "if you are

getting the oceans right, you are probably getting the atmosphere right."

Naomi Lubick

Links:

NASA

press release and link to animation

James

Hansen's Web site with links to publications

Back to top

Untitled Document

Results

from a new assessment show that Earth is absorbing more energy than it releases

into space. With implications for climate change, researchers say the study

points to future warming with consequences for ice sheets and sea level.

Results

from a new assessment show that Earth is absorbing more energy than it releases

into space. With implications for climate change, researchers say the study

points to future warming with consequences for ice sheets and sea level.