Geotimes

Untitled Document

News Notes

Space Weather

Sunspot outlook 2012

The future of the sun appears spotty,

according to some solar scientists. By incorporating physical observations of

the sun into a model, some scientists predict that the sun will boast more sunspots

during its next cycle than previous estimates anticipated.

The future of the sun appears spotty,

according to some solar scientists. By incorporating physical observations of

the sun into a model, some scientists predict that the sun will boast more sunspots

during its next cycle than previous estimates anticipated.

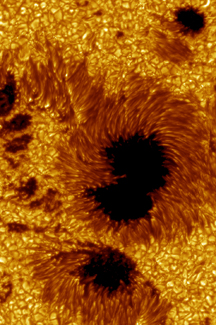

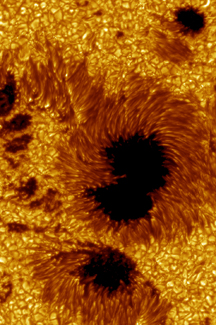

The Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope imaged

these sunspots in July 2002. A new model predicts that about six years from

now, the solar cycle will peak with higher numbers of sunspots than scientists

previously estimated. Image is courtesy of Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Appearing on the sun as dark blotches, sunspots are typically associated with

solar storms, in which the sun ejects high-energy particles that sometimes head

in the direction of Earth. Thus, the ability for scientists to accurately forecast

sunspot activity — the intensity of which peaks about every 11 years —

has implications for everything from protecting astronauts from the particles

during spacewalks, to reducing the potential negative interference with satellites

in orbit and even communications on Earth, such as cell phones.

For years, researchers have been working to better predict the intensity and

timing of solar activity, in effect creating a “space weather” outlook.

Until now, models have relied on the statistics gleaned from the outcome of

previous solar cycles to extrapolate that trend into the future.

In a new type of model, Mausumi Dikpati, a solar scientist at the National

Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., and colleagues chose instead

to use physical observations of the sun from space-borne instruments. In the

March 3 Geophysical Research Letters, Dikpati’s team reports that

the peak of the next cycle will be 30 to 50 percent stronger than the peak of

the current cycle, which peaked in 2000.

Previously, scientists could “do a reasonable job” at “guessing”

whether future cycles would be stronger than previous cycles, says Philip Scherrer,

a physics professor at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif., who worked

on previous solar forecasts. But the new approach of calibrating the model with

data from the sun’s interior, “is really quite interesting,”

he says.

Tools aboard NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (called SOHO), designed

to study the sun and its effect on space weather, aid in the imaging of the

sun’s interior. By introducing sound waves that reverberate within the

sun, researchers can “see” the structure of the sun, in much the same

way seismologists can use sound waves to see Earth’s interior.

The instruments’ data suggest that layers of the sun rotate at different

speeds at various points from the equator. Near the sun’s surface, gas

acts as a conveyer belt that moves magnetic remnants of the current cycle’s

sunspots from their original positions toward the sun’s poles. Next, that

magnetic field is carried into the sun’s interior, where it combines with

fields from previous cycles, forming the seed for the next cycle’s sunspots.

Dikpati and colleagues added these and other solar observations that distinguish

individual solar cycles into a predictive model. They tested the model by back-forecasting

the intensities of the sun’s previous eight cycles, and found that indeed,

the tool successfully simulated the relative intensity of those cycles.

If the data and assumptions are correct, Scherrer says, then the forecast proposed

by the model “seems like a pretty good prediction.” The findings,

however, contrast a forecast by other solar scientists, whose models predict

that the next cycle’s peak will be about 40 percent weaker than the last,

Dikpati and colleagues wrote. That study is based on the observation that sunspots

did not fully develop during the previous cycle, which the researchers think

might have been a result of changes in the sun’s conveyer belt.

To find out which model correctly predicts the next cycle, astronomers will

have to “wait a few years,” Scherrer says. The next cycle is expected

to peak sometime around 2012.

Kathryn Hansen

Back to top

Untitled Document

The future of the sun appears spotty,

according to some solar scientists. By incorporating physical observations of

the sun into a model, some scientists predict that the sun will boast more sunspots

during its next cycle than previous estimates anticipated.

The future of the sun appears spotty,

according to some solar scientists. By incorporating physical observations of

the sun into a model, some scientists predict that the sun will boast more sunspots

during its next cycle than previous estimates anticipated.